Is the dictionary dead? Or merely changing?

Also in this week’s digest: Why Morse Code didn’t work for Chinese + Words affect us based on how they sound + Your brain processes language more alike to AI than we previously thought

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Digest, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics!

📢 Updates & Announcements

Announcements and what’s new with me and Linguistic Discovery.

🎗️ Reminder about price changes

Quick reminder that the price for a paid subscription to the newsletter will increase to $10/mo. (USD) starting on February 1. But if you’d like to keep the old price of $5/mo. for another year, you can buy an annual subscription now for $50 (which also gives you 2 months free).

Free subscriptions will remain free. Free subscribers get access to:

- regular articles

- weekly digest

Paying subscribers get access to bonus articles throughout the year, including:

- previews of my in-progress book

- behind-the-scenes content about my work documenting and revitalizing languages

- deep-dives on special niche topics

Don’t hesitate to email me if you have any questions or concerns.

🎙️ Panel: Writing linguistics for public audiences

If you’re a fellow LingCommer (linguistics communicator), you may be interested in a panel I’m participating in later today: “An author’s guide to public linguistics and publishing books”.

I have no small amount of imposter syndrome about participating in this panel since I’ve only just recently embarked upon my own book-writing journey, but nonetheless I hope to contribute some useful insights into writing linguistics for a public audience, and maybe some good questions for the other panelists too.

Register for the session here.

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week’s content from Linguistic Discovery.

Why do some people pronounce the ⟨g⟩ in longevity twice?

Some people pronounce longevity with one G and some people say it with two, but why? And why isn’t the word spelled ⟨longgevity⟩?

In this week’s issue of the newsletter, I explain how longevity got its pronunciation: a combination of the evolution of Latin into the Romance languages, how our brains process language, how spelling relates to pronunciation, and how language changes over time. There’s a lot packed into understanding such an innocuous word!

Learn all about the history of longevity and its pronunciation here:

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

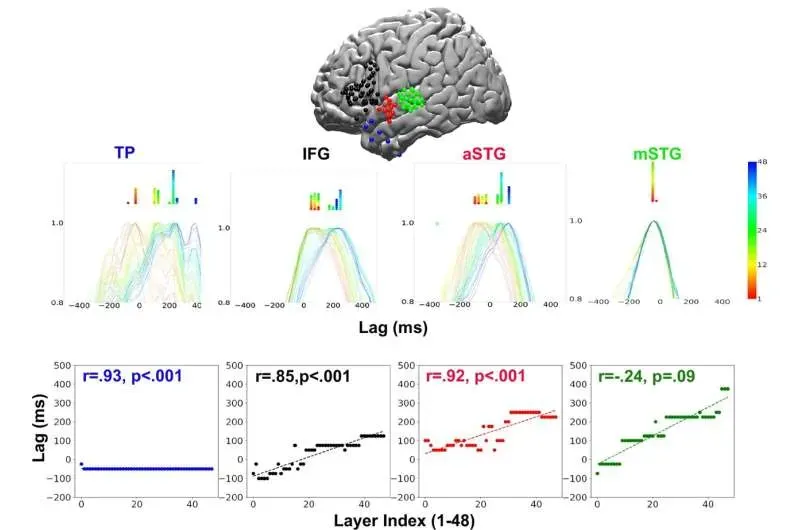

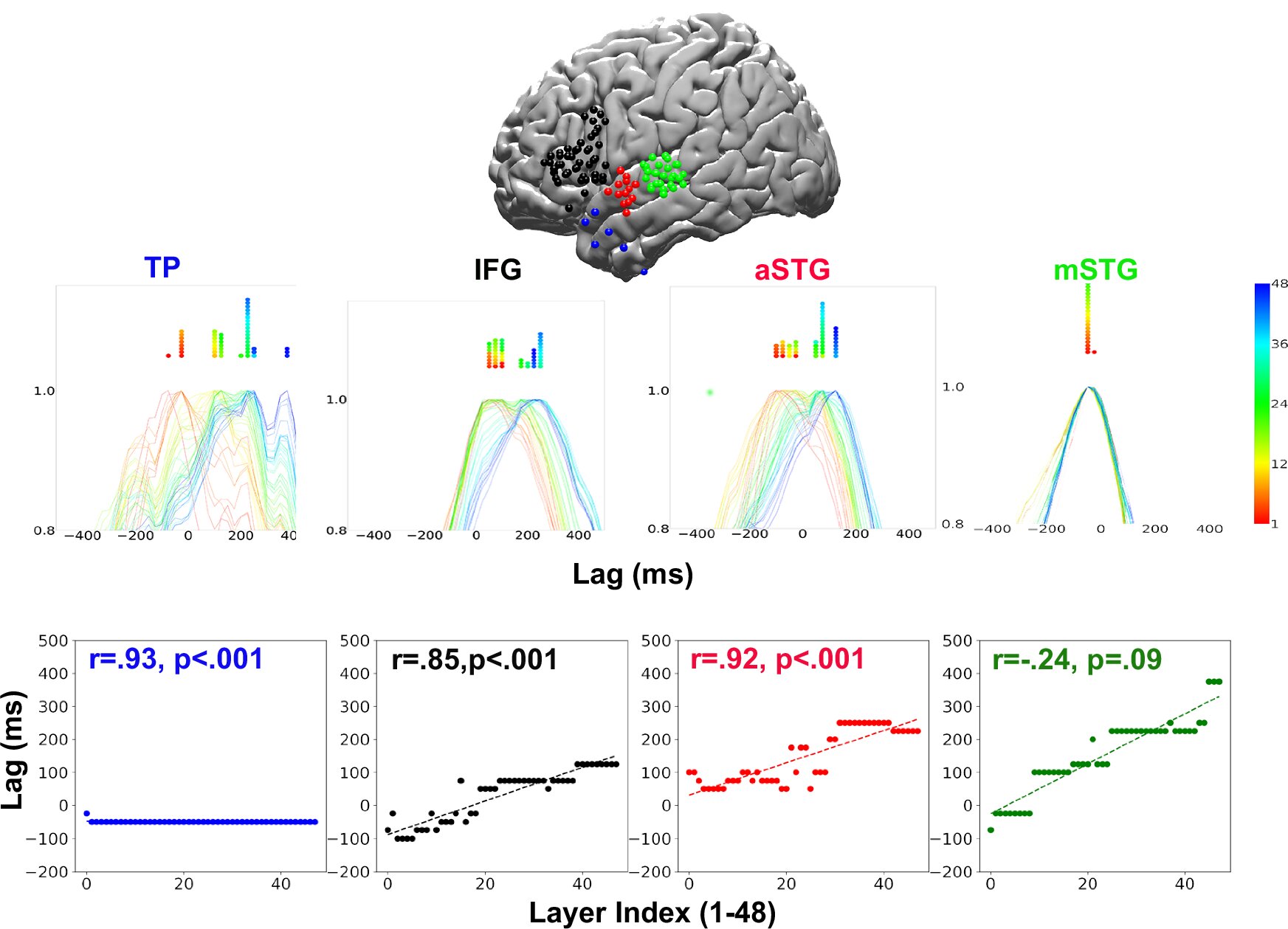

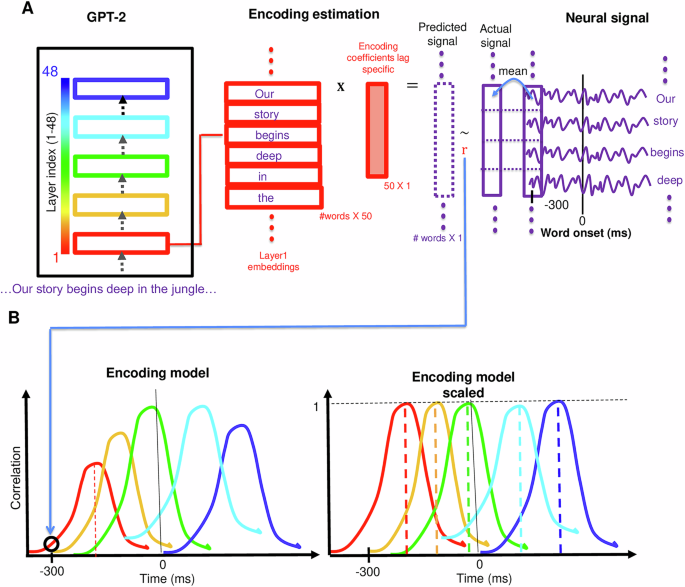

How your brain understands language may be more like AI than previously thought

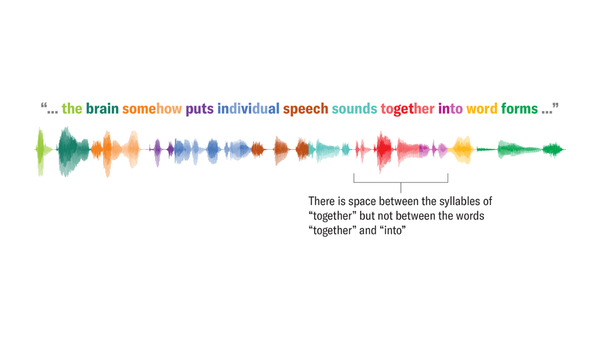

A new study reveals that the human brain processes spoken language in a sequence that closely mirrors the layered architecture of advanced AI language models. Using electrocorticography data from participants listening to a narrative, the research shows that deeper AI layers align with later brain responses in key language regions such as Broca's area. The findings challenge traditional rule-based theories of language comprehension and introduce a publicly available neural dataset that sets a new benchmark for studying how the brain constructs meaning.

Words affect us based on how they sound

A new study finds that highly vivid words sound more surprising to us than other words, challenging the traditional assumption in linguistics that the relationship between a word and its meaning is arbitrary and conventionalized. [I actually take issue with this characterization. Linguistic science has accumulated evidence for over half a century that the connection between words and their meanings isn’t entirely arbitrary. For example, linguists have been aware of iconicity in language since at least as early as Roman Jakobson’s 1965 article “Quest for the essence of language”, and later John Haiman’s work in the 1980s (e.g. Iconicity in syntax). The concept of iconicity predates even them, going back to Charles S. Pierce, a philosopher of language. Yet another study showing that language is marginally sound symbolic therefore isn’t particularly iconoclastic, nor does it alter the consensus that language is at its core an arbitrary system of conventional signs. Of course, that doesn’t make this study any less interesting!]

- Kilpatrick & Bundgaard-Nielsen. 2025. Say it like you mean it: Linguistic vividness and the attentional optimization hypothesis. Cognition 269(106406). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2025.106406.

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I’ve come across this week.

- Polari: The lost-and-found language of gay men (Babel: The Language Magazine)

- Accessible online to Babel subscribers.

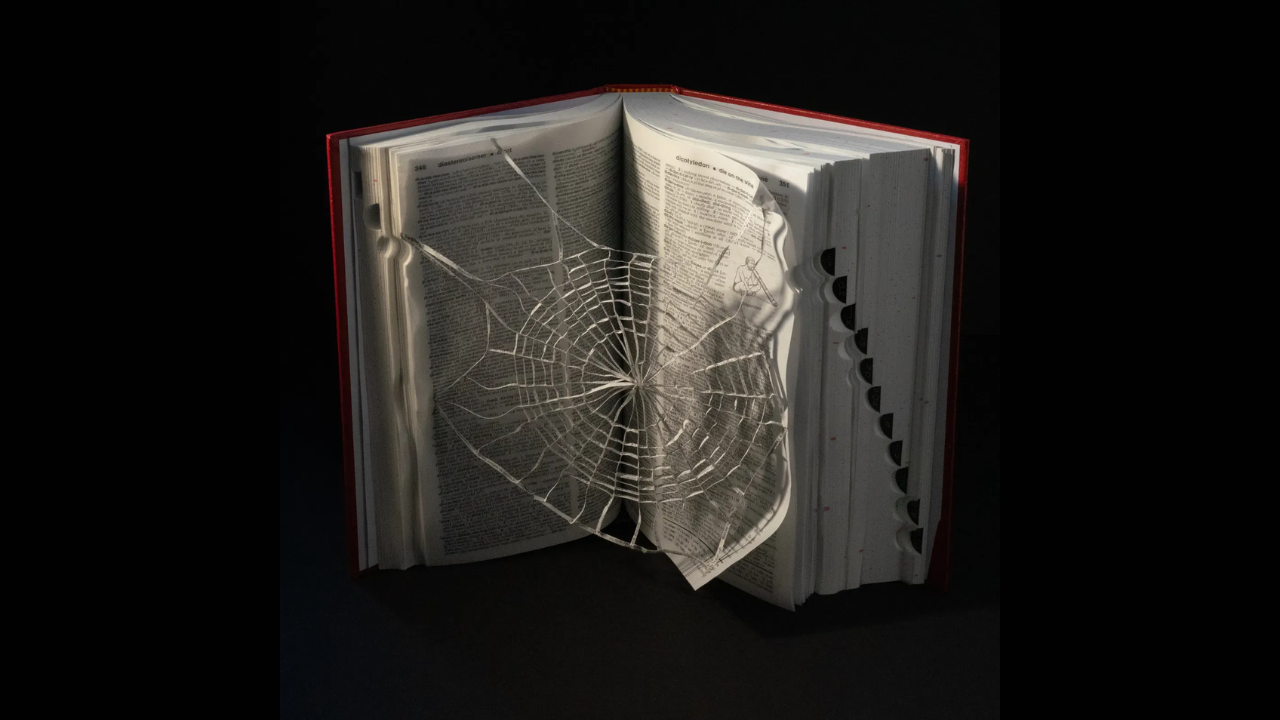

- Merriam-Webster recently released the 12th edition of their popular collegiate dictionary, which is probably what spurred this article into creation. I got my own copy of it and I have to say, it’s pretty darn nice.

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

Why Morse Code didn’t work for Chinese—and the genius fix

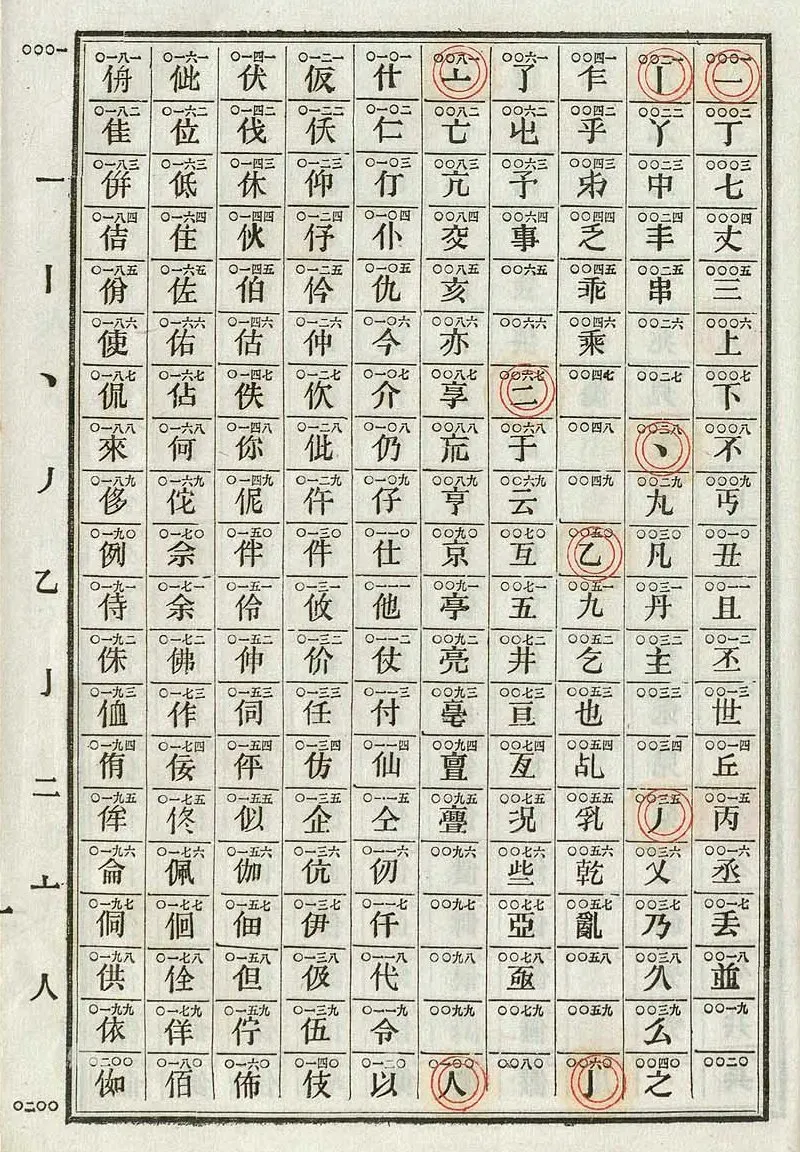

Morse code revolutionized global communication in the 1840s, but it posed a unique challenge for Chinese: how do you encode tens of thousands of characters using just dots and dashes designed for 26 letters? The ingenious solution was the Chinese telegraph code, developed in 1871 by the Great Northern Telegraph Company of Denmark.

The system assigned each Chinese character a unique four-digit number from 0000 to 9999. Telegraph operators would look up characters in a codebook arranged by radical and stroke order, transmit the numbers using standard Morse code, and the receiving operator would reverse the process. This meant that instead of devising entirely new dot-dash patterns for thousands of characters, Chinese could piggyback on existing telegraph infrastructure.

This early encoding system was more than just a practical communication tool—it represented a crucial moment in the history of Chinese language technology. The four-digit codes later influenced the development of Chinese typewriters and ultimately paved the way for modern Chinese computing. The Chinese telegraph code remained in use well into the 20th century, and the challenge of inputting Chinese characters on keyboards with limited keys continues to this day, though solutions like pinyin input and predictive text have made it seamless.

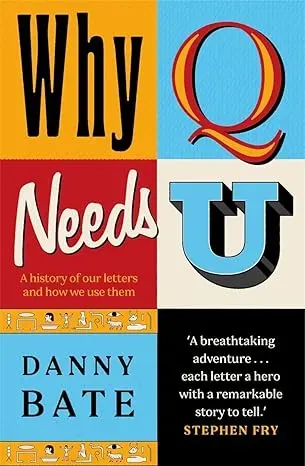

The history of the history of Indo-European

Lingthusiasm recently aired a great interview with Danny L. Bate, linguist and author of the book Why Q needs U: A history of our letters and how we use them (which Linguistic Discovery readers recently got a sneak preview of).

👋🏼 Til next week!

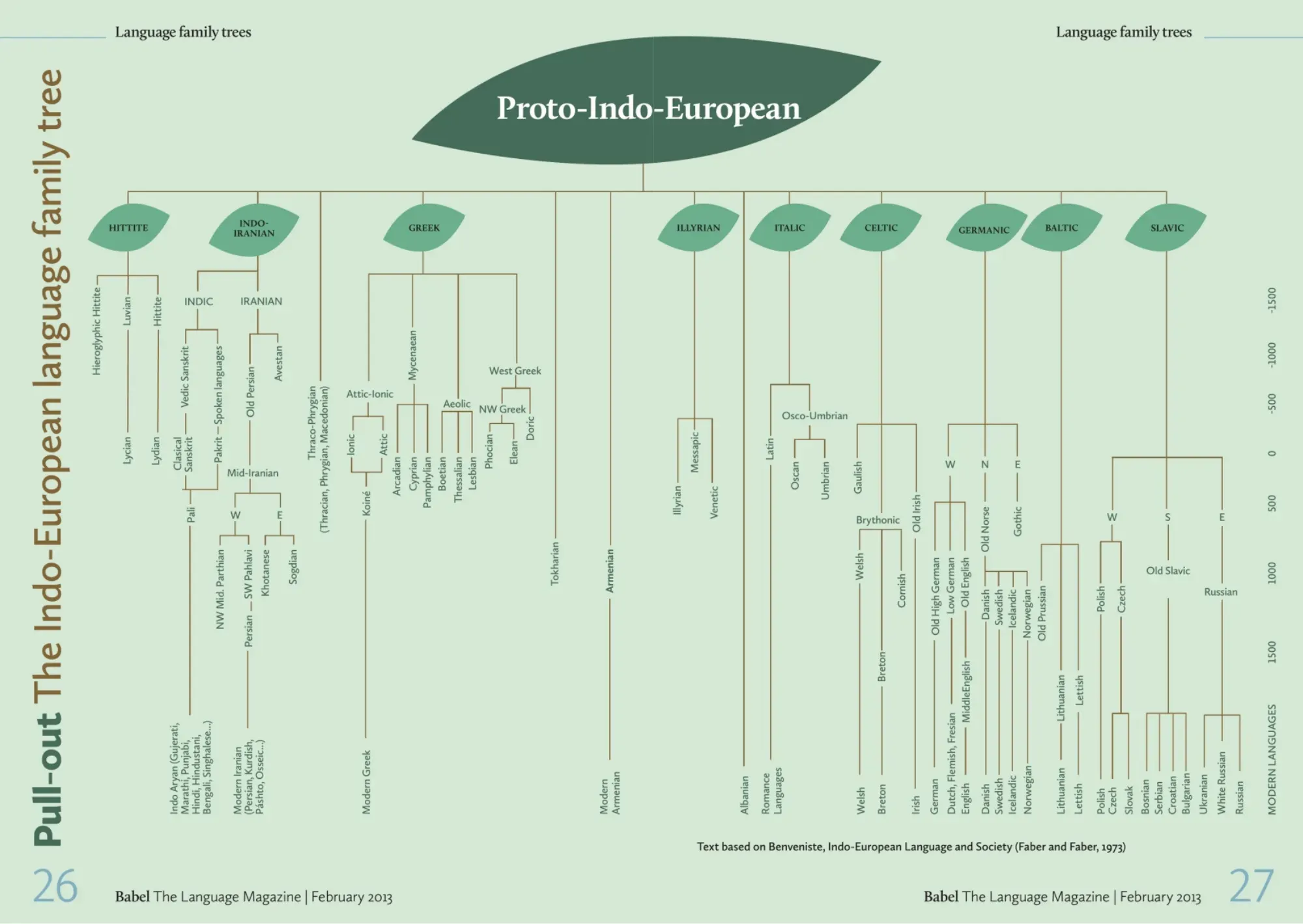

Family trees for Indo-European are often pretty messy and hard to read, so it was nice to come across this one that’s neatly laid out in Babel: The Language Magazine. (Note that this tree is based on a 1973 book, so it doesn’t represent the current consensus about branching etc.)

Get your own subscription to Babel: The Language Magazine here:

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.