Honeyguide birds learn regional human dialects

Also this week: People with personality disorders use language differently + Decoding the lost scripts of the ancient world. Here’s what happened this week in language and linguistics.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Digest, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics!

📢 Updates & Announcements

Announcements and what’s new with me and Linguistic Discovery.

2026 LingComm Grants

Small grants for communicating linguistics to wider audiences

The 2026 LingComm Grants are $300 (USD) to support linguistics communication projects that bring pop linguistics to broader audiences in new and engaging ways. The grants also include a mentoring meeting with Gretchen McCulloch, Lauren Gawne, and/or an experienced lingcommer who Gretchen & Lauren have personally selected to be relevant to your project to ask your lingcomm process questions, and promotion of your project to their lingthusiastic audience. [Note that I’ve volunteered as one of the “experienced lingcommers” they mentioned, so there’s a chance I could wind up being the person assigned to your mentoring meeting!]

There are six $300 LingComm Grants on any topic related to linguistics and an additional $300 Kirby Conrod and Friends LGBTQ+ LingComm Grant.

The initial grants are funded by Lingthusiasm and judged by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. You can help fund the grants and other LingComm projects here.

For more information, and to apply, visit the Grants page of the LingComm website.

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week’s content from Linguistic Discovery.

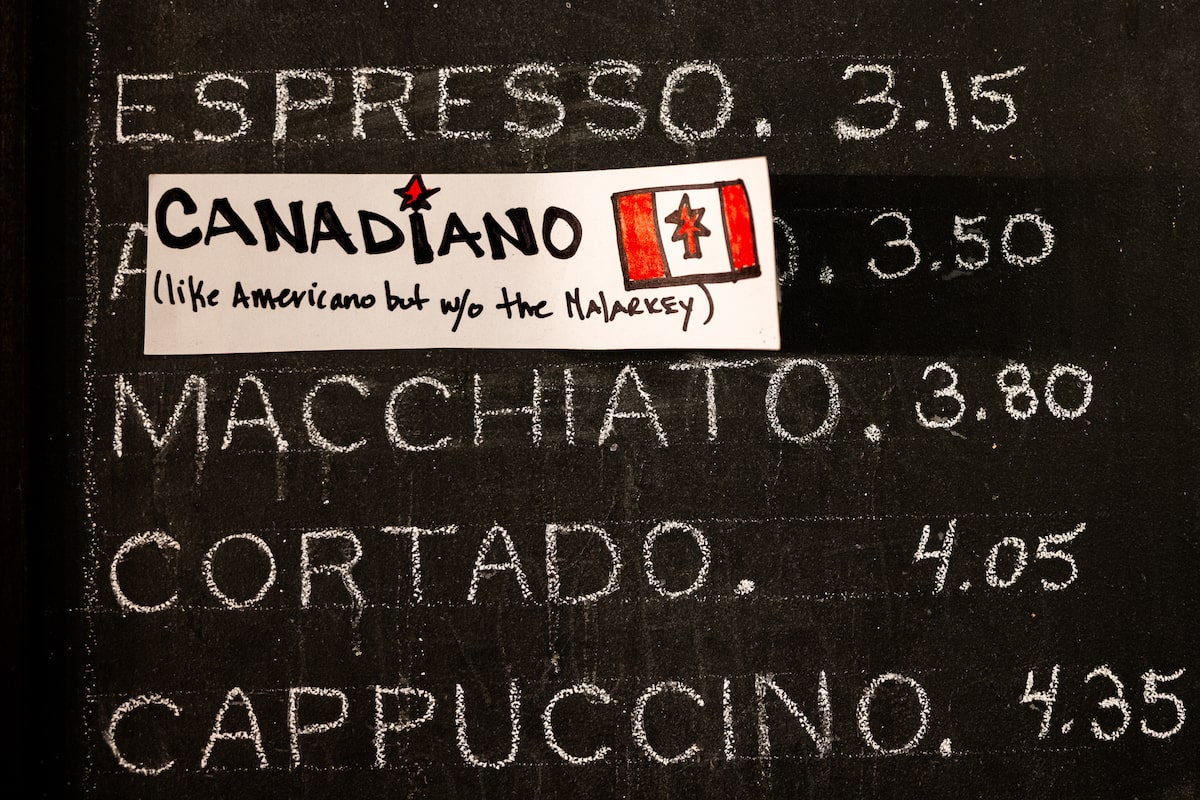

Libfixes: When word parts go rogue

There’s a revolution happening in English, and the affixes are winning. They’re breaking free from their original words, declaring independence, and forming new allegiances.

- ‑cation no longer belongs to vacation

- ‑pocalypse has abandoned apocalypse

- ‑flation has defected from inflation

Now they league with the likes of staycation, snowpocalypse, and stagflation. The affixes have been liberated. Call it what you want—Affixgate, Affexit, Affixception—but in linguistics these rogue word parts are known as libfixes (‘liberated affixes’).

In this week’s newsletter I provide you with some linguotainment about these unusual words:

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

People with personality disorders often use language differently

A new study finds that personality dysfunction leaves detectable traces in everyday communication. The researchers analyzed the written essays of 530 people and collected data on their levels of personality dysfunction. (Personality functioning exists on a spectrum.)

Those with greater personality dysfunction used language that carried a sense of urgency and self-focus – “I need…”, “I have to…”, “I am…”. This was expressed alongside ruminative, past-tense wording. They also had more negative, particularly angry, emotion terms, such as “furious” and “annoyed”. At the same time, they used noticeably less intimate or affiliative language such as “we”, “love” and “family”.

In a second study, the researchers looked at both essays and conversations:

Across both written and spoken communication, those with more dysfunctional or disordered personalities used more negative emotion words – and a wider variety of them. Even during mundane conversations, their language carried heavier negative affect, indicating a preoccupation with negative feelings.

Finally, the researchers examined nearly a million Reddit posts from 992 people who self-identified as having a personality disorder:

Those who frequently engaged in self-harm used language that was markedly more negative and constricted. Their posts contained more self-focused language and more negations – such as “can’t”. They also used more sadness and anger terms, and more swearing, while referencing other people less. Their wording was also more absolutist, reflecting all-or-nothing thinking, favouring words like “always”, “never”, or “completely”.

Awareness of these tendencies can help friends, family, and mental health professionals better identify and assist people of varying levels of personality functioning.

Honeyguide birds learn human signals for hunting honey

In parts of sub-Saharan Africa, honey-hunters and honeyguides [a wild bird that guides people to bees’ nests in exchange for access to beeswax] cooperate with each other to gain access to wild bees’ nests, and coordinate their behavior using distinctive calls. Cooperation between species allows humans to find and harvest more honey, and honeyguides to feed on more wax, thanks to honey-hunters’ skilled use of fire and tools to subdue the bees and open their nest. This long-standing partnership is one of the few known cases of cooperation between humans and wild animals.

A new study finds that there is regional variation in the specific calls, trills, grunts, whoops, and whistles that honey-hunters use to attract a honeyguide over long distances, and the quieter coordination calls used while following a honeyguide at close range. But what’s especially neat about this is that the honeyguide learns the regional dialects.

- van der Wal et al. 2026. Cooperative human signals to honeyguides form local dialects. People & Nature. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002%2Fpan3.70234.

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I’ve come across this week.

I strongly disliked this article and its title. If a word had no use/value, people wouldn’t use it. Obviously, however, an incredibly large number of people find the words discussed in this article to be useful and meaningful.

Word of the Year announcements also do more than merely “draw attention” to their publishers. The purpose of this tradition for many organizations, and especially the American Dialect Society, is to educate people about how language works, and hopefully combat some of the negative ideologies people have towards different ways of speaking.

The article also foregrounds the fact that most words of the year don’t have significant longevity, but the vast majority of new words don’t last long, no matter how “legitimate” they may seem. It’s anybody’s guess which ones will actually still around in the long run.

You can read my more detailed defense of a recent word of the year here:

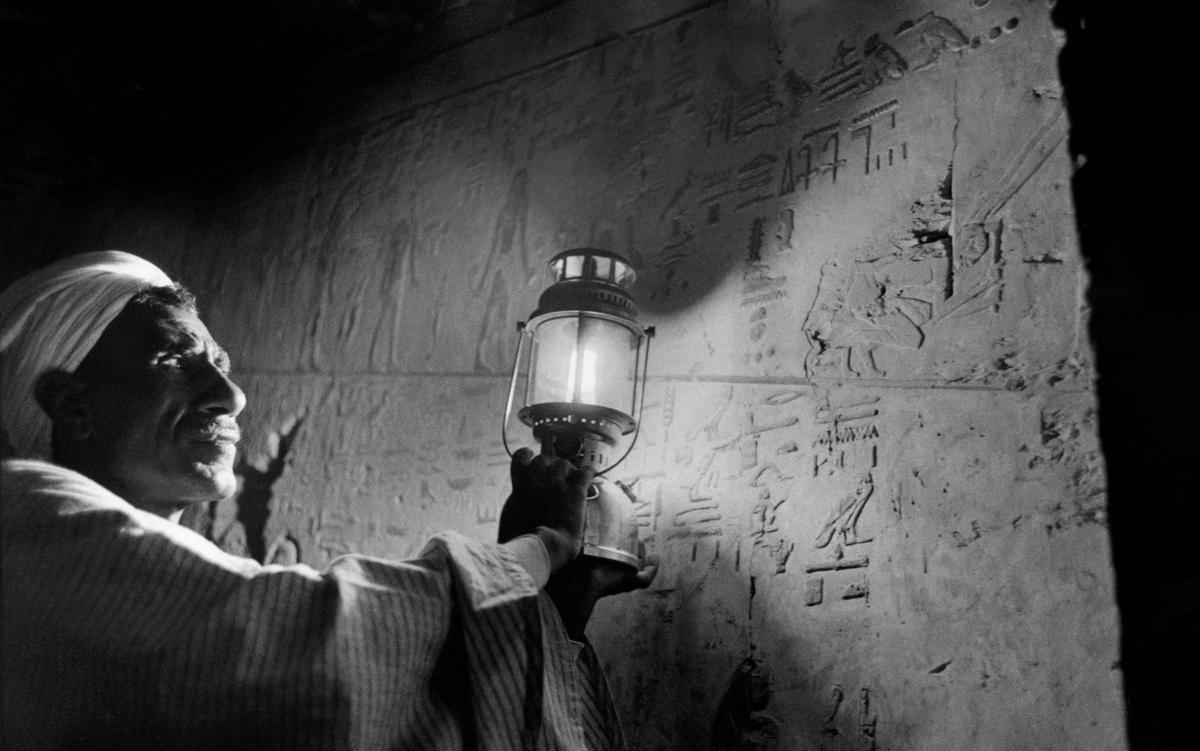

- Across the globe, a race is under way to crack some of the last mysterious forms of writing that have never been translated. Here’s how new technology and fresh breakthroughs might help scholars solve the world’s most vexing puzzles and rewrite history.

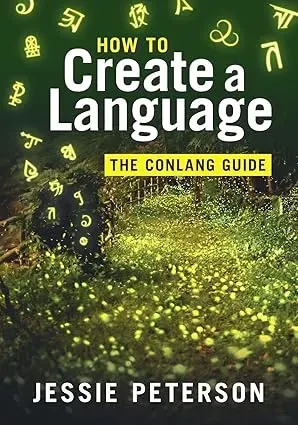

And a couple articles on the Na’vi language from James Cameron’s Avatar movies:

And some accompanying book recs:

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

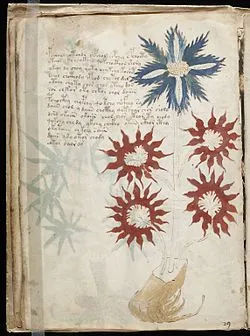

The Voynich Manuscript on Lingthusiasm

Lingthusiasm’s latest bonus episode is all about the mysterious Voynich manuscript, which was discovered in the 1600s and dates to the 1400s, and contains an undeciphered (and perhaps undecipherable) script. I greatly admire all of Dr. Bowern’s work, and her work on the Voynich manuscript is especially fun. Well worth a listen. (Patreon offers a 7-day free trial if you want to listen without becoming a paid supporter.)

The mysterious Voynich manuscript: Interview with Claire Bowern (Lingthusiasm)

Why we talk funny

Historically it’s been difficult to find books aimed a general audience about sociolinguistics, which is a real shame because it’s one of the most applicable and relatable areas of linguistics, that probably has the most to teach people. So I’m very happy to see this new book from Valerie Fridland, author of Like, literally, dude: Arguing for the good in bad English (Amazon | Bookshop.org). Here’s the publisher’s blurb:

Accents have long held our fascination. As far back as the 7th century BCE, Egyptian pharaohs experimented with babies to test out theories about the “original” accent and the Old Testament relays how a small difference in the pronunciation of “s” became a fatal litmus test of tribal belonging. Still today, from dinner parties to job interviews, you’ll find people kicking up dust about things like where and how to pronounce a ‘t,’ as in, never in “often,” but with proper British poshness, as in “t(y)une.”

In Why We Talk Funny, linguist Valerie Fridland unlocks the secrets of what linguistic science, psychology and history can tell us about the evolution of human speech, why accents develop, and how they shape our professional and social lives. With a healthy dose of her signature humor and captivating anecdotes, Fridland explores how the twin forces of physiology and psychology along with the need to fit in changes the trajectory of speech over languages and lifetimes, diving deep into the history and social forces driving the way people talk. Along the way, she emphasizes that accents don’t always set us apart, they can also bring us together. Whether it’s the accent that hints at your hometown, your group, your social status or your ethnicity, the sounds we say reveal a lot about who we are and where we’ve been – even for those who might think they have no accent at all.

The story of language is the story of humanity, and as Fridland reminds us, the funny sounds we make – whether from the mouths of ancient ancestors or the tongues of screenbound teens – all come from the same powerful desire to communicate and belong. Why We Talk Funny will change the way you think about your own accent – and transform the way you listen to the sounds of others.

The book releases on April 21. You can preorder your copy here:

👋🏼 Til next week!

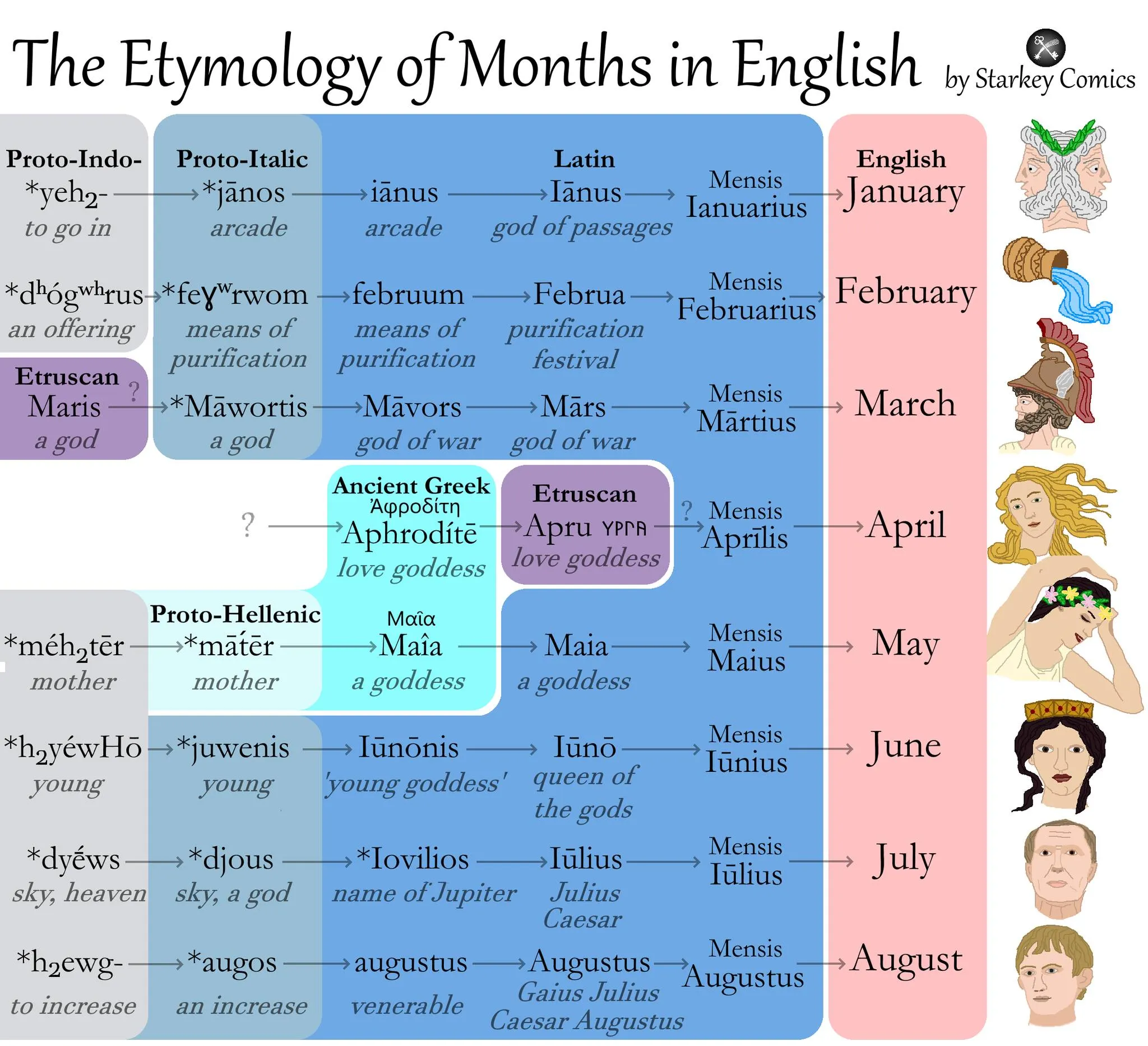

The etymology of months in English, from Starkey Comics.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.