Language may not be so hierarchical after all: A new study challenges 70 years of linguistic theory

Also this week: Some dogs learn words like children + “How to kill a language”, a new book by Sophia Smith Galer

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Digest, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics!

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week’s content from Linguistic Discovery.

Why is February spelled with two ⟨r⟩’s?

Hint: It’s not because English speakers originally pronounced it that way!

Find out more in this free issue of the newsletter:

Why do people use baby talk? The science of baby talk, Part 2

What is baby talk, and why do parents use it in the first place? Does it really have a role to play in a child’s language acquisition, or is it nothing but useless cutesy word play?

Learn all about the surprisingly sophisticated strategies and tactics that caregivers use to make their speech more accessible to their children in this second issue of my special series on the science of baby talk:

Here’s the entire series:

ℹ️ Articles in this Series

- Part 1: Why you should be talking to your infant

- Part 2: Why do people use baby talk?

- Part 3: Is baby talk good for your child? (forthcoming)

- Part 4: Do all cultures use baby talk?

- Part 5: Baby talk in the languages of the world

- Part 6: How much should you talk to your child?

- Part 7: What really matters when talking to your child

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

Some dogs can pick up hundreds of words—do they learn like children?

A new study finds that certain exceptional dogs, called “gifted word learners”, may have learned the names of objects (like a squirrel) merely from overhearing their owners talking. Interestingly, this ability doesn’t seem to be breed-specific. The study used an approach designed to study how well human toddlers understand words, but applied it to dogs. They found that the dogs in the study were able to learn words through overhearing just like 1.5-year-old children—and sometimes even better!

- Dror et al. 2026. Dogs with a large vocabulary of object labels learn new labels by overhearing like 1.5-year-old infants. Science 391(6781). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.adq5474.

Language may not be so hierarchical after all

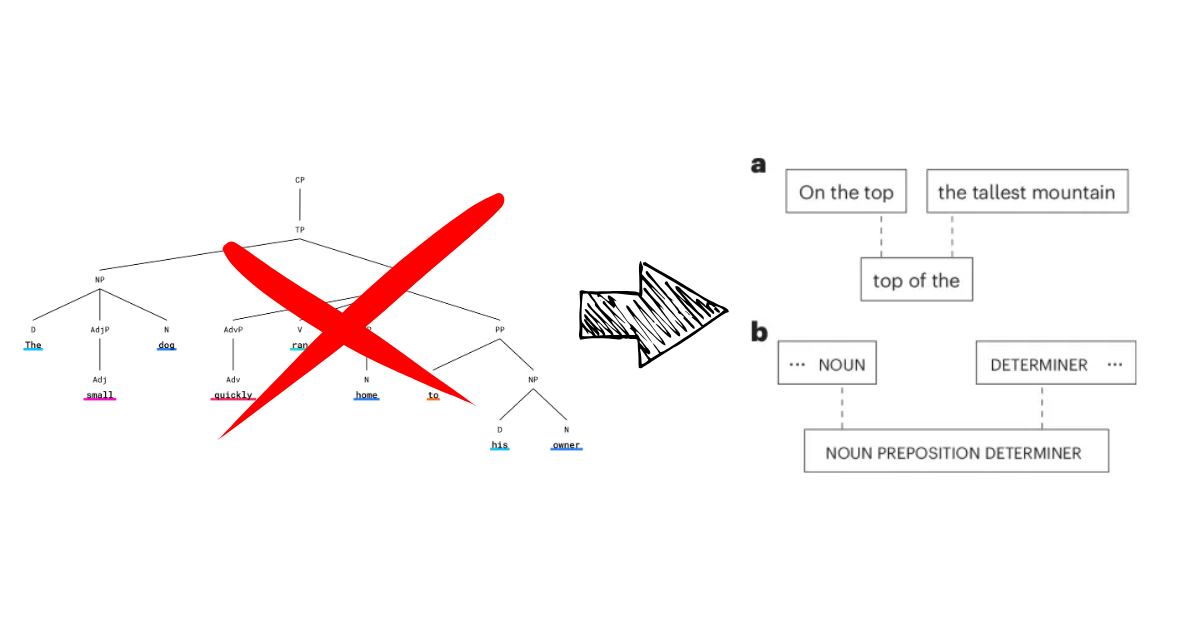

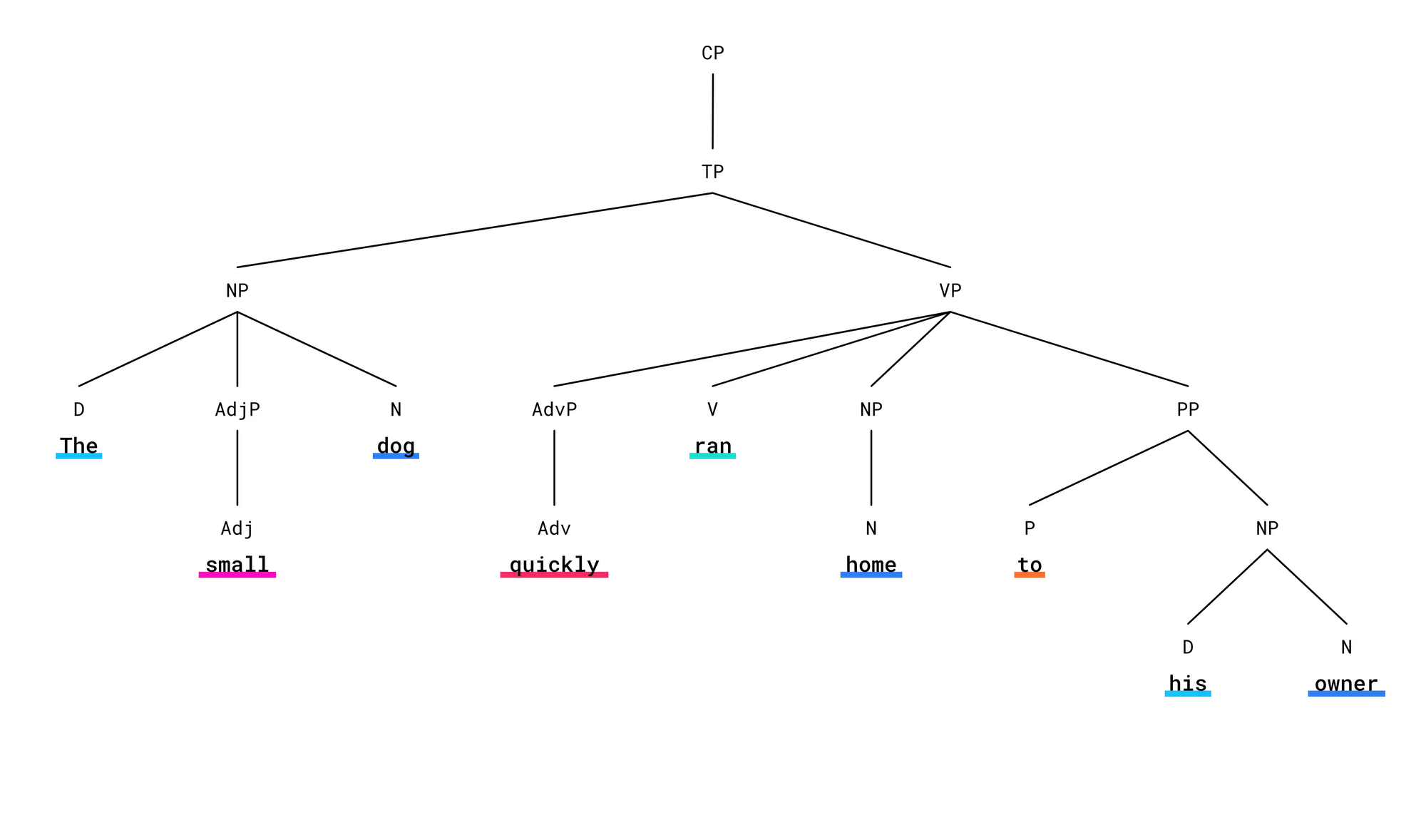

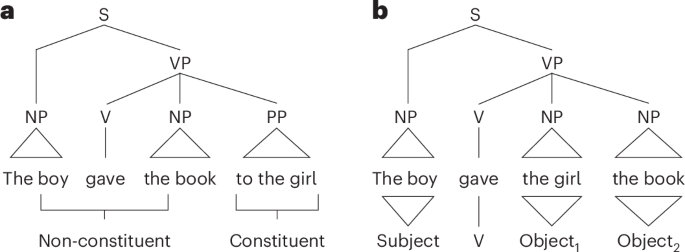

Noam Chomsky popularized a highly formalized, highly mathematized model of language in the 1960s which assumes that language is fundamentally hierarchical—that is, tree-like, as in the following diagram.

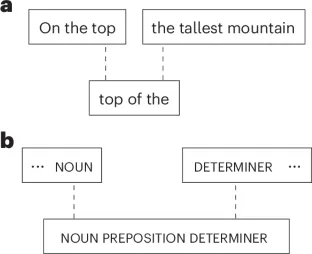

This approach predicts that when people construct sentences in their heads as they’re speaking, they’re not merely thinking about the next word in the sentence, but rather building an entire complex hierarchy, and paying attention to the relationships between each of words and phrases and their constituents. However, humans are capable of recognizing simple linear patterns too, so it’s not strictly necessary to assume that all language is hierarchical. Instead, it may be that people construct sentences more like assembling a puzzle, where pieces of different templates fit into each other, like the image below.

A new study uses a set of experiments to show that this non-hierarchical approach to language structure may in fact be more realistic than traditional hierarchical ones.

- Have we been wrong about language for 70 years? New study challenges long-held theory (SciTechDaily)

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I’ve come across this week.

- For my own take on this topic, check out this article on the origins of writing:

- In Taiwan they call @ “little mouse”. It's “dog” in Russian, “strudel” in Hebrew and “monkey’s tail” in Dutch. The @ sign is a mirror, and its story goes back thousands of years.

- Greek's place in the story of European language is well known, but its role in the linguistic history of Asia and Africa is just as impressive.

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

The language of liars

Speak another people’s language. Know them. Become them. And discover you’ve destroyed them.

A forthcoming sci-fi book is causing some buzz among language nerds: The language of liars, by S.L. Huang. One reviewer says, “Pitch-perfect science fiction about linguistics and consequences. This book destroyed me.” It’s also been selected as a New Scientist Best of 2026 Pick and a Most Anticipated Pick for Library Hub, Book Riot, and Shelf Reflection. The book has definitely piqued my interest, so I might try to get an advance reviewer copy and let you know what I think.

How to kill a language: Power, resistance, and the race to save our words

A forthcoming book from UK journalist and fellow content creator Sophia Smith Galer looks and how languages are lost and what happens when they disappear:

An urgent, globe-spanning exploration of languages at risk, from Kichwa to Ukrainian, that asks: What do we lose—culturally, politically, and personally—when a language is silenced?

Languages can be killed in many ways: war, the climate crisis, nationalism, and even quiet choices made at the dinner table. Around the world, an unprecedented shift is drawing speakers toward national and global lingua francas. For some, that means losing the language of parents or grandparents; for many, it is a permanent farewell to systems that carry knowledge, culture, and belonging. With half of our 7,000 languages due to disappear this century, linguicide is one of the most pressing cultural emergencies of our age.

In How to Kill a Language, journalist Sophia Smith Galer travels across continents and generations to chart this phenomenon. In Ecuador, she sees firsthand how shame deters parents from passing Kichwa onto their children. In Oman, she learns about languages with roots older than Arabic but never officially recognized. And in Italy, she searches for her Nonna’s dialect, which is vanishing from diaspora communities and Italy itself. But languages can also be reclaimed: We meet the Karuk tribe of California, pioneering a grassroots language immersion program, and the storytellers challenging the criminalization of Kurdish. And in her discussion of Hebrew, Smith Galer reckons with the unintended consequences of raising a language seemingly from the grave.

Part investigation, part travelogue from a disappearing world, How to Kill a Language exposes the true costs of this mass extinction event. Brought to life by vivid storytelling and Smith Galer’s own experience with language loss, it’s a fierce rallying cry for a multilingual future.

👋🏼 Till next week!

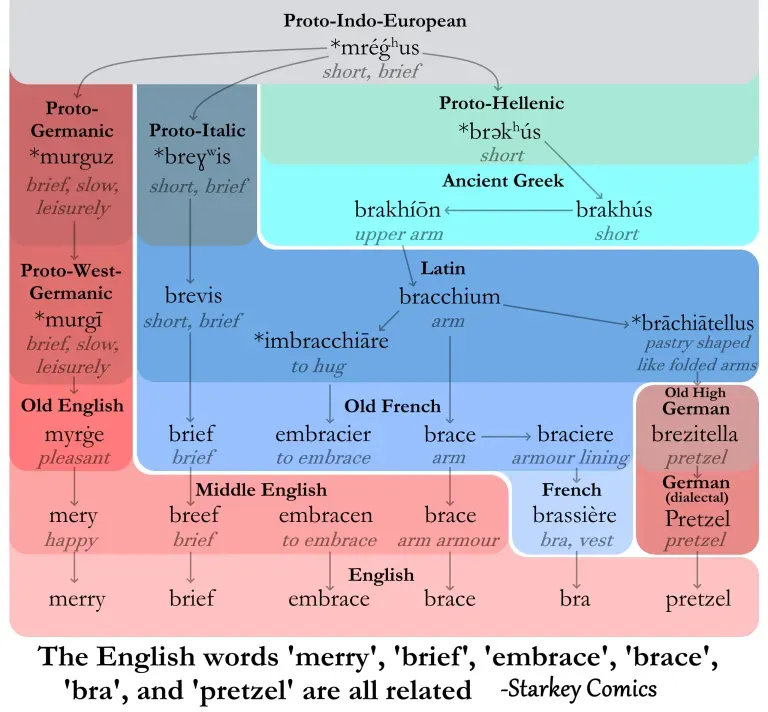

Here’s another fun etymological diagram from Starkey Comics, this time some surprising doublets! Did you know that merry, brief, embrace, brace, bra, and pretzel are all related? Read the blog post here for details.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.