Is baby talk good for your child?

Does using baby talk make language learning easier, or does it hinder your child’s language development?

Is baby talk good or bad for your child? Does using nonsense or simplified words hinder their language development? Or does it make acquiring language easier for them? Parents are often deeply divided on this issue. Some parents insist that you should only speak to children like adults because it models correct language for them, while others say that baby talk is helpful and makes it easier for your child to learn language. Here are just a few of the comments I got on social media when I asked for opinions about it:

There’s a difference between “parentese” and baby talk! Parentese is used in conjunction with English (or whatever your native tongue is). Gibberish generally isn’t helpful in developing language skills. (link)

“Motherese” is pervasive across cultures and may be something we've evolved to do. It would seem odd to me that we do it as we do if there weren't some evolutionary advantage. (link)

I never bothered with baby talk with all of the bubs I've cared for, including my 2. I couldn't see the point. Not sure if this was the reason, but my siblings & my children & now my grandchildren, all have an extensive & varied vocabulary & excellent command of the English language. (link)

It seems to me that baby talking to them teaches them a particular pitch, prosody, and vocabulary that they’ll then have to unlearn whenever the parent decides to start talking “normally” to them. I have four children and while one is just barely past a year old, the others are 2.5, 4, and 13, and they have all three spoken very well for their ages—we never allowed baby talk around them. Perhaps a case of “correlation but not causation,” but I don’t believe so. (link)

It depends on what you mean? Short sentences and sweet nicknames? Fine. Making up silly words, speaking incorrectly or saying words wrong on purpose to be cute? Bad. (link)

Good! When kids are very little, using the two-word sentences they say can help with comprehension. Not saying to do baby talk exclusively, but a well placed “find shoes?” or “want snuggle?” can streamline understanding and effective communication (link)

You are raising adults! Go ahead and baby talk if you have speech therapy money (link)

What do you mean by baby talk? Slow, sing-song intonation? Great! Adults deliberately using incorrect grammar like “me want cookie” when speaking to babies? Bad! And also fuckin weird! Nursery words? No idea but I’ve never met a six year old who doesn’t know that “choo choo” and “train” are the same thing so I doubt it’s a big deal and I have had fights in person about it when someone other than the kid’s parents tried to tell me not to say “bunny rabbit.” (link)

I always talked my kids with an adult voice. Why should they have to learn a second vocabulary and grammar? (link)

It’s not beneficial. Infants are apers. They mimic their parents and learn. Talk to them like people, so they learn to speak like people. (link)

This question got a lot more responses than I was expecting! According to a poll I posted on Instagram and Threads with several hundred responses on each platform, the overall bias was in favor of baby talk:

Poll: Is baby talk good or bad for your child?

| Threads | ||

|---|---|---|

| It’s good | 40% | 37% |

| It’s bad | 30% | 36% |

| Not sure | 30% | 26% |

This is an issue that people are divided and passionate about! So which take is correct? Today we’ll consider the advantages and disadvantages of baby talk in this third installment in my series on the science of talking to babies. Be sure to subscribe below to get notified when the other issues in this series go live!

ℹ️ Articles in this Series

- Part 1: Why you should be talking to your infant

- Part 2: What’s the point of baby talk?

- Part 3: Is baby talk good for your child? (this issue)

- Part 4: Do all cultures use baby talk? (forthcoming)

- Part 5: Baby talk in the languages of the world

- Part 6: How much should you talk to your child?

- Part 7: What really matters when talking to your child

Does baby talk even work?

The amount and type of input that children receive does matter, contra the claims of the linguistic nativists.

A 2006 book about child language acquisition states:

[Being told] “Your instinct is supported by science” is, of course, just the kind of thing that parents like to hear. But let’s get the facts right. Preference for motherese does not establish its necessity, or even its usefulness. […] For all we know, motherese is neither good nor bad for child language learning: it is simply irrelevant. Language learning is remarkably resilient. All you need to do is to talk to children—baby-talk or otherwise—and biology will take care of rest. (Yang 2006: 101–103)

While the second part of this claim is undeniably true—your children will learn language proficiently as long as you speak to them regularly—the subsequent two decades of research since the book was published have shown a number of benefits from using baby talk (also called infant-directed speech (IDS)). The perspective represented in that book stems from a time when the majority of linguists believed that grammar is genetically endowed—that we have a “language instinct”, to use Steven Pinker’s phrase—a position called linguistic nativism. Because grammar is hardwired into us, the thinking goes, it doesn’t really matter how much or what kind of language children are exposed to. Children merely need to be exposed to a language, and then their language instinct will kick in and apply those innate grammatical rules to whatever language it is they’re hearing (or seeing, in the case of infants exposed to sign language). That innate grammar—called Universal Grammar—is thought to help children make sense of the messy, overwhelming, inconsistent language input they encounter in the world.

Linguist Noam Chomsky famously claimed that without an innate grammar, it was impossible for children to learn grammatical rules as proficiently as they do. He posited that the amount of linguistic data that children receive in infancy is simply insufficient for them to work out the complex rules of language—there exists a Poverty of the Stimulus, to use his term.

For linguistic nativists, whether adults use baby talk or regular speech with children is irrelevant, because Universal Grammar will impose the same innate grammatical rules regardless. However, advances in our understanding of cognition in the last several decades have inclined more and more researchers away from the nativist position. Many, perhaps the majority, of linguists now believe that children have all the cognitive tools they need to make sense of the messy language input they receive in infancy, without having to posit an innate grammar mechanism. This approach to language is typically referred to as cognitive linguistics due to its emphasis on aligning linguistic theory with insights from the rest of cognitive science.

One of the many pieces of evidence supporting the cognitive approach is the fact that baby talk does in fact have significant effects on a child’s linguistic proficiency. In the last three decades especially, a growing body of research has demonstrated that the amount and type of linguistic input children receive really does affect their knowledge of language.

For example, children tend to master the most frequent elements of their language first. Morphemes that are used with high frequency on many different word stems in adult speech, such as the plural ‑s in English, typically appear early in the child’s speech (Clancy 2018: 352). Children of mothers who use more yes/no questions in their speech acquire auxiliary verbs earlier (Newport, Gleitman & Gleitman 1977 ). And the frequency of a given word in adult speech, along with the number of uses in one-word utterances and the length of the word, predicts children’s comprehension and production of those words at 15 months (Clark 2024: 38).

Another great example of the importance of frequency in language acquisition is how children learn Peninsular (Spain) Spanish vs. Mexican Spanish: In Peninsular Spanish, the present perfect tense (e.g. he comido ‘I have eaten’) is more common than it is in Mexican Spanish. As a result, the first tense contrast that Spanish children learn is the present tense vs. the present perfect tense, whereas the first tense contrast that Mexican children learn is the present tense vs. the past preterite tense (e.g. comí ‘I ate’) (Chee et al. 2023: 381). Similarly, in Mexican Spanish the plural /s/ is almost always expressed, but in Chilean Spanish the /s/ is unpronounced in certain contexts. As a result, Chilean children take longer to master the formation of plurals than Mexican children do (Chee et al. 2023: 381).

The type of input children receive matters too: one study found that the greater the proportion of commands that a caregiver used with their children (as opposed to questions), the less complex the children’s verb phrases and noun phrases were later on. The same researchers also found that more frequent use of words that rely on context (deixis), such as this, that, then, you, here, them, etc., correlates with vocabulary growth and children’s later development of noun phrases. (Newport, Gleitman & Gleitman 1977)

All this shows us that the amount and type of input that children receive does matter, contra the claims of the linguistic nativists. But what about baby talk specifically? We turn to this in the next section.

Is baby talk good for your child?

Social interaction is key to the language-learning process.

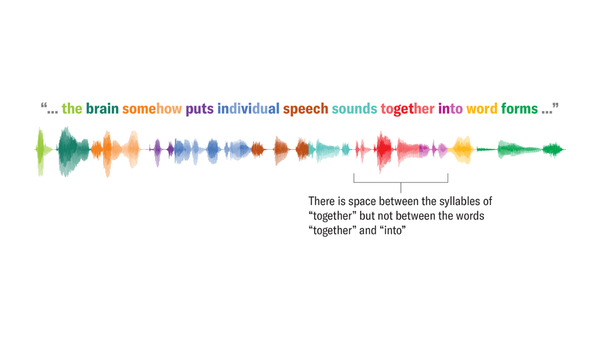

The main way that baby talk helps children learn language is by making it easier for children to understand what’s being said to them, through slower, exaggerated speech, simpler syntactic constructions, and targeted choice of vocabulary. This was the main point of Part 2 of this series on baby talk, so you can read all about the details of those features of baby talk there. But that’s only part of how baby talk benefits children.

For starters, it’s well established that babies prefer listening to infant-directed speech (IDS)—and particularly IDS with exaggerated prosody—over other types of speech (Cooper & Aslin 1990; Cooper 1993; Hernik & Broesch 2019; The ManyBabies Consortium et al. 2020). This matters for language learning because it helps get the child’s attention! Infants remember individuals who address them in IDS better than those who don’t, and look longer at them. This in turn makes the child more interesting to the adult, who is then more likely to continue using IDS with them! (Schachner & Hannon 2011) One study shows that infants who are good at observing their caregiver’s mouth and following their gaze acquire vocabulary especially quickly (Tenenbaum et al. 2015).

However, the preference for IDS over adult-directed speech starts to wane around the child’s first birthday (Ibbotson 2022: 66), which may be why adults use IDS most prominently during the child’s first year but less so later (Saxton 2017: 88). This is another great example of how adults subconsciously adjust their speech to the needs and preferences of the child over time, as I emphasized in Part 2 of this series.

The exaggerated prosody and pronunciation used in baby talk also have positive effects for children’s language acquisition: infants whose parents hyperarticulate speech sounds perform better at discriminating between consonants in their parents’ language (Liu, Kuhl & Tsao 2003), and exaggerated vowels and slower speaking rates help infants recognize words better (Song, Demuth & Morgan 2010).

Infants who were receiving a greater amount of IDS at 18 months also had larger expressive vocabularies by 25 months (Weisleder & Fernald 2013). This was specifically correlated with IDS, and not speech simply overheard by the child. Social interaction is key to the language-learning process. Use of IDS with an infant also predicts greater lexical diversity, length of utterances, and frequency of conversational turn-taking in the child’s speech at age 5 (Ferjan Ramírez et al. 2024). (It’s important to point out here that this is just a correlation. Other aspects of the child’s environment likely contribute to their conversational style, vocabulary size, and utterance lengths as well.)

We’ll explore other benefits of IDS in a later installment in this series, but suffice it to say for now that baby talk is basically all benefits and no drawbacks. So if you’re a caregiver worried about the detrimental effects of baby talk on your infant, rest easy—you’re simply making the incredibly complex task of language learning easier for them.

Nonetheless, baby talk isn’t strictly necessary for successful child language acquisition. This raises some fascinating questions: Is baby talk universal? Do all parents use it? Do all cultures use it? In the next issue, we’ll look at baby talk in the languages of the world! Be sure to subscribe to the newsletter if you haven’t already in order to receive future issues in this series.

ℹ️ Articles in this Series

- Part 1: Why you should be talking to your infant

- Part 2: What’s the point of baby talk?

- Part 3: Is baby talk good for your child? (this issue)

- Part 4: Do all cultures use baby talk? (forthcoming)

- Part 5: Baby talk in the languages of the world

- Part 6: How much should you talk to your child?

- Part 7: What really matters when talking to your child

📚 Recommended Reading

How babies talk: The magic and mystery of language in the first three years of life

Understanding child language acquisition

📑 References

- Chee, Melvatha R., Frances V. Jones, Jill P. Morford & Naomi L. Shin. 2023. Usage-based approaches to child language development: Insights from studies of Navajo, ASL, and Spanish. In Manuel Díaz-Campos & Sonia Balasch (eds.), The handbook of usage-based linguistics (Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics), 379–392. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Clancy, Patricia M. 2018. First language acquisition. In Carol Genetti (ed.), How languages work: An introduction to language and linguistics. 2nd edn. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108553988.

- Clark, Eve V. 2024. First language acquisition. 4th edn. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009294485.

- Cooper, R. P. 1993. The effect of prosody on young infants’ speech perception. Advances in Infancy Research 8. 137–167.

- Cooper, Robin Panneton & Richard N. Aslin. 1990. Preference for infant-directed speech in the first month after birth. Child Development 61(5). 1584–1595. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130766.

- Ferjan Ramírez, Naja, Yael Weiss, Kaveri K. Sheth & Patricia K. Kuhl. 2024. Parentese in infancy predicts 5-year language complexity and conversational turns. Journal of Child Language 51(2). 359–384. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000923000077.

- Hernik, Mikołaj & Tanya Broesch. 2019. Infant gaze following depends on communicative signals: An eye‐tracking study of 5‐ to 7‐month‐olds in Vanuatu. Developmental Science 22(4). e12779. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12779.

- Ibbotson, Paul. 2022. Language acquisition: The basics (The Basics Series). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003156536.

- Liu, Huei‐Mei, Patricia K. Kuhl & Feng‐Ming Tsao. 2003. An association between mothers’ speech clarity and infants’ speech discrimination skills. Developmental Science 6(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7687.00275.

- Newport, Elissa L., Henry Gleitman & Lila R. Gleitman. 1977. Mother, I’d rather do it myself: Some effects and non-effects of maternal speech style. In Catherine E. Snow & Charles A. Ferguson (eds.), Talking to children: language input and acquisition, 101–149. Cambridge University Press.

- Saxton, Matthew. 2017. Child language: Acquisition and development. 2nd edn. SAGE.

- Schachner, Adena & Erin E. Hannon. 2011. Infant-directed speech drives social preferences in 5-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology 47(1). 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020740.

- Song, Jae Yung, Katherine Demuth & James Morgan. 2010. Effects of the acoustic properties of infant-directed speech on infant word recognition. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 128(1). 389–400. https://doi.org/10.1121/1.3419786.

- Tenenbaum, Elena J., David M. Sobel, Stephen J. Sheinkopf, Bertram F. Malle & James L. Morgan. 2015. Attention to the mouth and gaze following in infancy predict language development. Journal of Child Language 42(6). 1173–1190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000914000725.

- The ManyBabies Consortium, Michael C. Frank, Katherine Jane Alcock, Natalia Arias-Trejo, Gisa Aschersleben, Dare Baldwin, Stéphanie Barbu, et al. 2020. Quantifying sources of variability in infancy research using the infant-directed-speech preference. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 3(1). 24–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919900809.

- Weisleder, Adriana & Anne Fernald. 2013. Talking to children matters: Early language experience strengthens processing and builds vocabulary. Psychological Science 24(11). 2143–2152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613488145.

- Yang, Charles D. 2006. The infinite gift: How children learn and unlearn the languages of the world. Scribner.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.