Hawaiian only has 8 consonants—What happens when it borrows words with other sounds?

The Hawaiian language only has 8 consonants. So how does it deal with sounds in words borrowed from other languages?

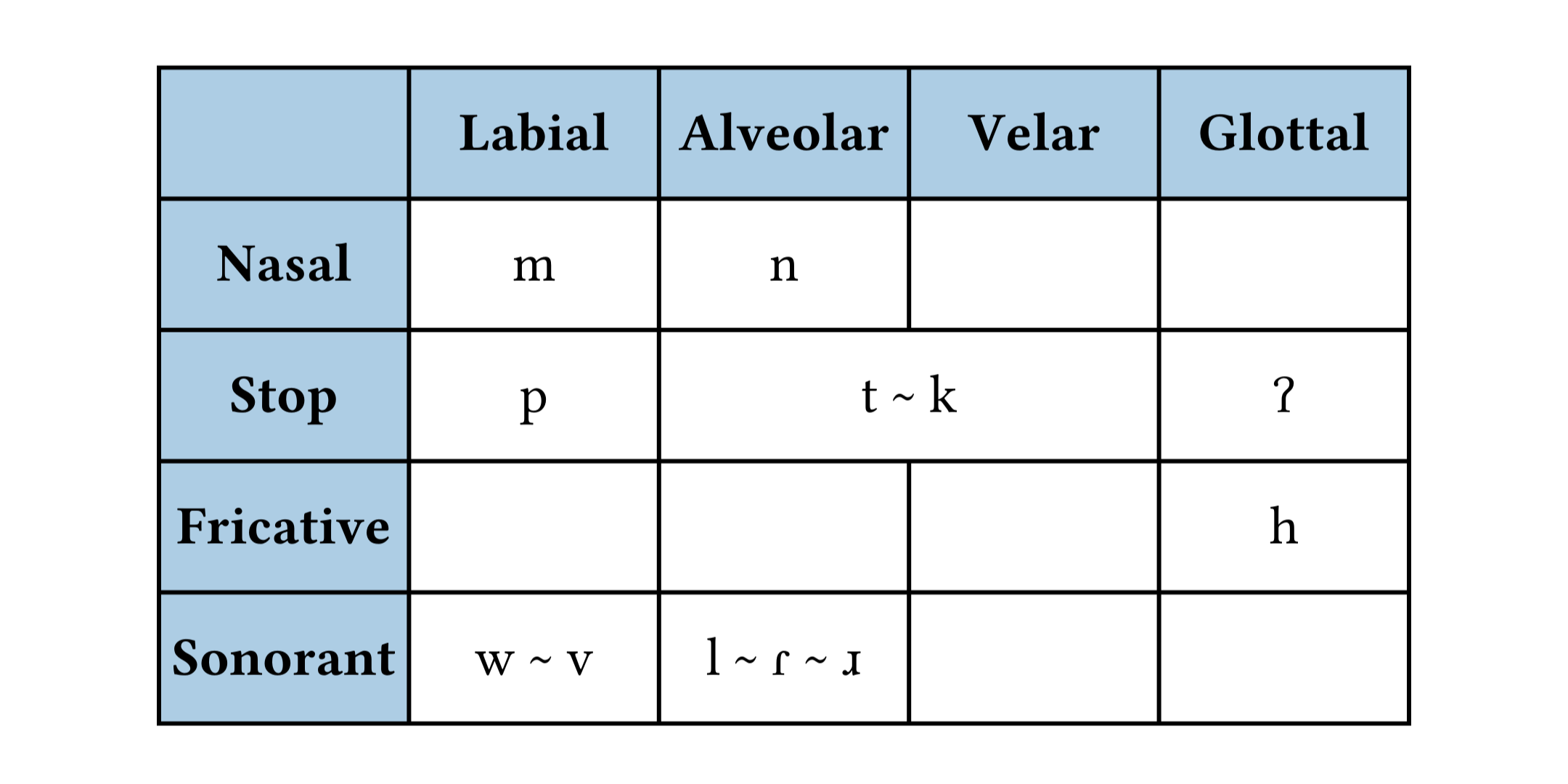

The Hawaiian language only has 8 consonant sounds (phonemes), making it one of the smallest consonant inventories of any language in the world. (The smallest consonant inventory goes to Rotokas with only 6!) (Gordon 2016: 44)

By comparison, most dialects of English have 24 consonants, Mandarin is typically analyzed as having 19 consonants, and Spanish has around 18 depending on the dialect. The average number of consonants in a language is 22.8 (Gordon 2016: 44), so Hawaiian’s 8 is pretty small!

So what do Hawaiian speakers do when they borrow words that have foreign sounds?

Prefer a video version of this post? Watch here!

First, most of the consonants get converted to /k/. The /k/ sound does a lot of heavy lifting in Hawaiian. Since the only other stop consonants in the language are /p/ and /ʔ/, any stop consonant that isn’t a bilabial or glottal stop can function as /k/—even [t]! The Hawaiian language doesn’t distinguish between [k] and [t]—they are functionally the same sound. So makua ‘parent’ might be pronounced as either [makua] or [matua] with no functional difference. Speakers recognize it as the word makua either way. Certain dialects will pronounce /k/ as [t] more frequently than other dialects, which prefer a [k] pronunciation, but it’s all considered the same phoneme. (Wikipedia: Hawaiian phonology)

The result is that all the English sounds /s z ʃ ʒ t d tʃ dʒ g/ are converted to /k/ when borrowed into Hawaiian. Here are some examples:

| English | Hawaiian |

|---|---|

| truck | kalaka |

| blessing | pelekine |

| speak | kapika |

| rabbit | lāpaki |

You may already know another famous borrowing: Mele Kalikimaka for English ‘Merry Christmas’, as sung by Bing Crosby & the Andrews Sisters:

Similar variation occurs with /w/ and /l/: speakers freely pronounce /w/ as either [w] or [v], and /l/ as either [l], [ɾ], or [ɹ]. So when an English word gets borrowed with one of these sounds, they get normalized to /w/ or /l/. Some examples:

| English | Hawaiian |

|---|---|

| beaver | piwa |

| acre | ʻakele |

| ginger | kinika |

Hawaiian syllables are also strictly either consonant-vowel (CV) or just a vowel (V). Syllables cannot end in a consonant. So in borrowed words, clusters of more than one consonant are either broken apart or simplified into a single consonant, while syllable-final consonants are either given an extra vowel or deleted entirely (Wikipedia: Hawaiian phonology):

| English | Hawaiian |

|---|---|

| bill | pila |

| island | ʻailana |

| scraper | kalepa |

Knowing all this, now you can see how all the following English words got borrowed into Hawaiian as kini (which also happens to be the native Hawaiian word for ‘multitude’).

- gin

- tin

- king

- kin

- zinc

- guinea

- Jean

- Jane

- Jenny

Lastly, even though Hawaiian may not distinguish between many of the sounds that exist in English, it does have one sound that English doesn’t—the glottal stop /ʔ/. English speakers certainly produce this sound quite a lot, but only in non-meaningful (subphonemic) ways:

- It’s the catch in the throat in the middle of the phrase uh-oh [ˈʔʌ.ʔoᶷ].

- In many dialects speakers can pronounce /t/s as glottal stops (most famously Australians when they pronounce “a bottle of water”).

- English speakers naturally insert a glottal stop at the beginning of words that start with a vowel: am is pronounced [ʔæm], and is pronounced [ʔænd], etc. (This is amusingly called the glottal attack or hard attack. 👅⚔️)

All these uses occur even though the glottal stop isn’t meaningful in English and speakers don’t hear it as a distinct phoneme.

But Hawaiian speakers can hear it, so it gets included in borrowed words. Canny readers may have noticed that the Hawaiian borrowing for ‘island’ above started with a glottal stop, for example. In the same way, the Hawaiian word in each of the following examples starts with a glottal stop because the English word starts with a vowel.

| English | Hawaiian |

|---|---|

| acre | ʻakele |

| anchor | ʻanakā |

| empire | ʻemepaea |

Of course, there are exceptions to all of these rules. Occasionally words will be borrowed with their foreign consonants in tact (savana ‘savanna’; mōchī ‘mochi’), or will retain their consonant clusters (kristo ‘Christ’), but for the most part words are assimilated to the Hawaiian sound system.

Now that you have a grasp of how borrowings work in Hawaiian, can you guess what English word was borrowed into Hawaiian as Kapalakiko? I’ll leave the answer at the very bottom of the page. ⬇️

📖 Further Reading

📑 References

- Gordon, Matthew K. 2016. Phonological typology (Oxford Surveys in Phonology & Phonetics 1). Oxford University Press. (Amazon | Bookshop.org)

- Haspelmath, Martin. 2017. Some principles for language names. Language Documentation & Conservation 11: 81–93. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24725

- Jones, ‘Ōiwi Parker. 2009. Loanwords in Hawaiian. In Haspelmath, Martin & Tadmor, Uri (eds.), Loanwords in the World’s Languages, 771–789. Walter de Gruyter. DOI: 10.1515/9783110218442.771. (Amazon | Bookshop.org)

- Watt, Dom & Jane Setter. 2024. “A clash of symbols: Special [k]”. Babel: The Language Magazine 48 (Autumn): 34–35. https://babelzine.co.uk/

If you'd like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.