Do Inuit languages really have more words for snow? And why does it matter, anyway?

A new study shows that Inuit languages really do have more words for snow, but what does that tell us about language?

One of the most infamous language tropes is the idea that Inuit languages have dozens or even hundreds of words for snow—more than any other languages. Now, this idea may or may not be true (more on that in a bit), but it’s instructive to understand where this trope came from in the first place. Here it is, from Franz Boas in the Handbook of American Indian languages (1911):

Another example of the same kind, the words for SNOW in Eskimo, may be given. Here we find one word, aput, expressing SNOW ON THE GROUND; another one, qana, FALLING SNOW; a third one*, sirpoq*, DRIFTING SNOW; and a fourth one, qimuqsuq, A SNOWDRIFT. (Boas 1911: 25–26)

That’s it. That’s the entire basis for the claim that Inuit languages have an exorbitant number of words for snow.

This idea was repeated and exaggerated in greater and greater numbers over the decades (Martin 1986), until by 1984 the New York Times reproduced the number as 100:

Benjamin Lee Whorf, the linguist, once reported on a tribe that distinguishes 100 types of snow – and has 100 synonyms (like tipsiq and tuva) to match. (“There’s snow synonym,” New York Times)

Why are people so obsessed with the “Inuit words for snow” myth? It has everything to do with the idea that language fundamentally affects the way we think. But is this idea true?

Does language influence the way we think?

Where things start to get really interesting is in the nuanced interplay between language and experience. Our conceptualizations and experiences shape our language, but our language also has subtle effects on our conceptualizations, creating a feedback loop.

The “Inuit words for snow” myth captures the popular imagination because it creates an exoticized image of peoples who “see the world differently” or “think differently” than English speakers. This is a version of an idea known as linguistic relativity (also called the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis)—the idea that the language a person speaks influences, limits, or determines the way that they perceive and conceptualize their worlds (Matthews 2014: 353; Crystal & Yu 2024: 398).

In one understanding of the idea, linguistic relativity is trivially true. All our experiences influence the way we think in extremely subtle ways, language included. This is no different than saying that the sport a person plays or the job a person does or how much exercise a person gets influences how they think about things. That’s all true, but also pretty unremarkable.

A more extreme version of the idea, called linguistic determinism, claims that we are locked into certain worldviews by the languages we speak. This claim is obviously false. The fact that people can successfully learn other languages is enough evidence that linguistic determinism cannot be literally true. Or consider this simple thought experiment: The Russian language has distinct words for ‘light blue’ (голубой goluboj) and ‘dark blue’ (синий sinij), yet English has just one word for both, blue. Are English speakers incapable of understanding the difference and distinguishing between the two colors because English lacks distinct words for them? Of course not. Languages are also not fixed entities—speakers of any language rapidly coin new expressions for ideas and things that are new to them.

Unfortunately, linguistic determinism has a sordid history of being used to justify all sorts of scurrilous claims about the inferiority of indigenous peoples, by both scholars and the public alike. For example, in a grammatical description of Inuit languages, philologist William Thalbitzer writes:

In the Eskimo mind the line of demarcation between the noun and the verb seems to be extremely vague, as appears from the whole structure of the language, and from the fact that the inflectional endings are, partially at any rate, the same for both nouns and verbs. […] Judging from these considerations, we get the impression that to the Eskimo mind the nominal concept of the phenomena of life is predominant. The verbal idea has not emancipated itself from the idea of things that may be owned, or which are substantial. Anything that can be named and described in words, all real things, actions, ideas, resting or moving, personal or impersonal, are subject to one and the same kind of observation and expression. […] The Eskimo verb merely forms a sub-class of nouns. (Thalbitzer 1911: 1057–1059)

Here we see a scholar using the purported lack of a grammatical distinction in the language to say that Inuit peoples are incapable of distinguishing objects from actions. In this view, their categorization of the world is hopelessly vague.

In another case the opposite was claimed: linguist Stephen Ullmann criticized some indigenous languages for being too specific instead:

To have a separate word for all the things we may talk about would impose a crippling burden on our memory. We should be worse off than the savage who has special terms for wash oneself, wash someone else, but none for the simple act of washing. (Ullmann 1951: 49).

Ullmann is unwittingly referring to Cherokee, which has its own version of the “Inuit words for snow” myth. In 1892, linguist Otto Jespersen described Cherokee as having 13 different verbs for washing, a claim which holds up to scrutiny just about as well as the “Inuit words for snow” myth (Hill 1952), as we’ll see below. But like the snow myth, that idea was propagated for decades afterwards by various scholars, with the result that a generation of intellectuals thought that the Cherokee were incapable of abstract thought.

The most famous claim about “the indigenous mind” comes from the progenitor of linguistic determinism himself, Benjamin Lee Whorf:

After long and careful study and analysis, the Hopi language is seen to contain no words, grammatical forms, constructions, or expressions that refer directly to what we call “time”. [A Hopi person] has no general notion or intuition of TIME as a smooth flowing continuum in which everything in the universe proceeds at an equal rate. (Whorf 1950: 67)

Yet in 1983, linguist Ekkehart Malotki published a hefty 677-page tome analyzing all the expressions for time in the Hopi language. The book opens with the following passage in Hopi, with accompanying translation:

pu’ antsa pay qavongvaqw pay su’its talavay kuyvansat, pàasatham pu’ pam piw maanat taatayna

‘Then indeed, the following day, quite early in the morning at the hour when people pray to the sun, around that time then, he woke up the girl again.’ (Malotki 1983)

Oops. Suffice it to say, Whorf’s analysis was slightly off.

These kinds of linguistically-motivated claims about the cognitive abilities of different peoples extend to more than just indigenous communities. It’s been claimed that because some languages lack dedicated morphological markers of future tense, speakers of those languages save less money and are generally worse at long-term, future-oriented decision-making than speakers of languages which do have a future tense (Chen 2013).

What’s especially ironic about this study is that most linguistic typologists (myself included) would include English in the group of languages lacking a dedicated future tense. But this study does the opposite, contrasting English with Mandarin Chinese, for example.

The paper concludes that speakers of non-tensed languages like Mandarin “save more, retire with more wealth, smoke less, practice safer sex, and are less obese”—huge if true. In fact, the author Keith Chen even gave a TED talk about his research, garnering over 250,000 views on YouTube:

Yet it turns out the study was deeply flawed: It did not take into account the fact that many languages in the study were related; it assumed that each language was independent. This assumption makes correlations appear stronger than are warranted (known as Galton’s problem in phylogenetics). In a follow-up study that controlled for relatedness and included Chen as a coauthor, the statistical correlation between tensedness and future-orientation was found to be insignificant, debunking Chen’s original study (Roberts, Winters & Chen 2015).

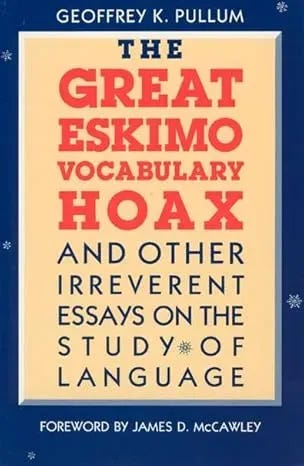

In addition to the pernicious beliefs propagated by uncritical acceptance of linguistic relativity, claims about linguistic relativity usually have the direction of causation wrong as well. It’s not that language shackles us into certain ways of seeing the world; it’s that language comes to reflect our conceptualizations of the world. Languages develop vocabulary and grammatical structures for things that speakers talk about frequently—a pretty trivial observation. Geoffrey Pullum trenchantly makes this point in his famous essay, “The great Eskimo vocabulary hoax”:

Among the many depressing things about this credulous transmission and elaboration of a false claim is that even if there were a large number of roots for different snow types in some Arctic language, this would not, objectively, be intellectually interesting; it would be a most mundane and unremarkable fact.

Horsebreeders have various names for breeds, sizes, and ages of horses; botanists have names for leaf shapes; interior decorators have names for shades of mauve; printers have many different names for different fonts (Caslon, Garamond, Helvetica, Times Roman, and so on), naturally enough. If these obvious truths of specialization are supposed to be interesting facts about language, thought, and culture, then I’m sorry, but include me out. (Pullum 1989: 278–279)

(Pullum’s article is available here, but the book version has an added appendix where Pullum attempts to get at a real number.)

Where things start to get really interesting is in the nuanced interplay between language and experience. Our conceptualizations and experiences shape our language, but our language also has subtle effects on our conceptualizations, creating a feedback loop. For instance, while it’s true that English speakers can distinguish light blue and dark blue, it turns out they can’t do it as well or fast as Russian speakers can:

- Winawer et al. 2007. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. PNAS 104(19): 7780–7785. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lera Boroditsky, one of the authors of the above paper, has an excellent TED talk (in the top 30 of TED’s most-viewed talks) describing some of the great research that’s been done in this area:

Do Inuit languages really have more words for snow?

Okay, so the original discussion got blown way out of proportion, sure, but could the claim that Inuit languages have lots of words for snow still be true, even if it doesn’t tell us anything scientifically interesting? After all, it’s entirely reasonable that a community would have an assortment of words for objects they deal with frequently.

Martin (1986) says that many of the words that people use to illustrate the snow myth are not actually words for snow at all, but refer to ice, drifts, moisture, igloos, etc. In actuality, she says, there are only two roots for ‘snow’—qanik ‘snow in the air; snowflake’ and aput ‘snow on the ground’.

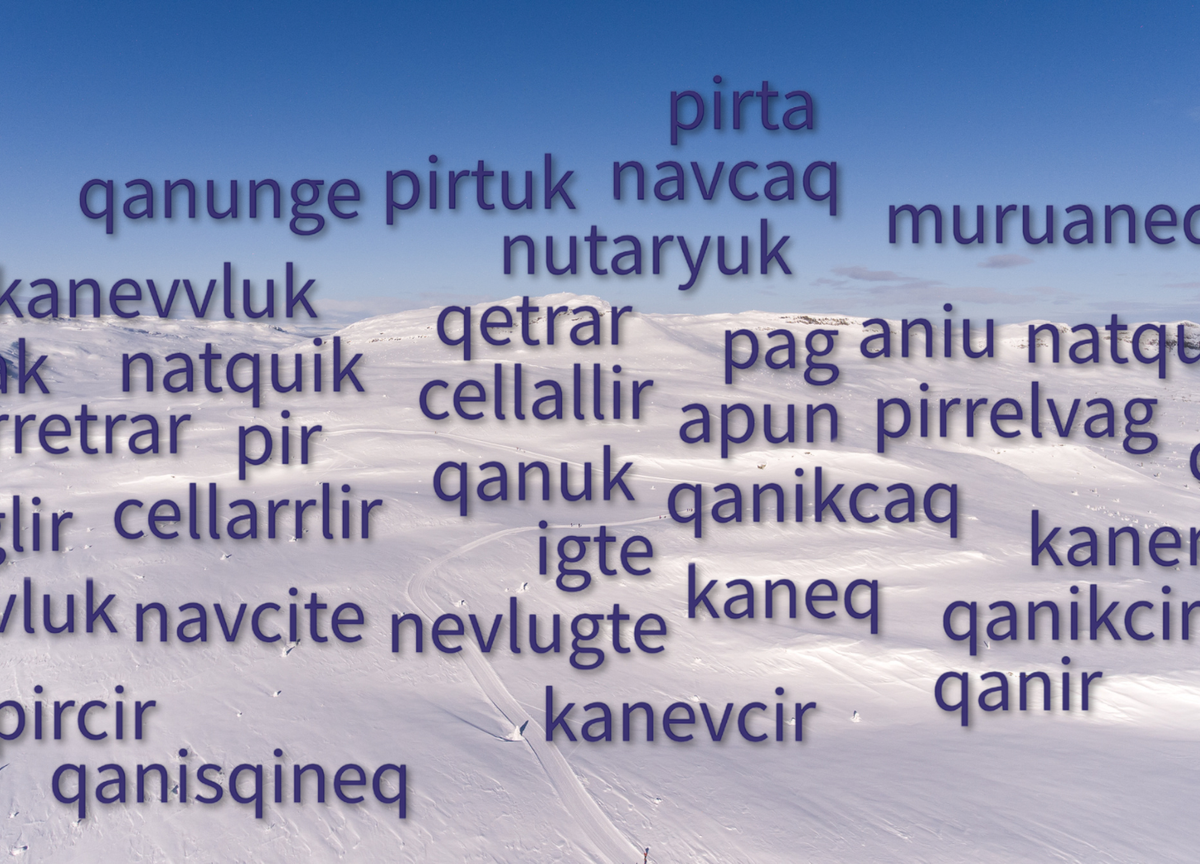

Linguist Anthony Woodbury comes to a more generous number. Using Steven Jacobson’s (1984) Yup’ik Eskimo dictionary, he finds 32 stems having to do with snow:

- aniu ‘snow on ground’

- aniu- ‘to get snow on ground’

- apun ‘snow on ground’

- cellallir-, cellarrlir- ‘to snow heavily’

- kaneq ‘frost’

- kaner- ‘to be frosty; to frost something’

- kanevcir- ‘to get fine snow/rain particles’

- kanevvluk ‘fine snow/rain particles

- muruaneq ‘soft deep snow’

- natqu(v)igte- ‘for snow, etc. to drift along ground’

- natquik ‘drifting snow, etc.’

- navcaq ‘snow cornice, snow (formation) about to collapse’

- navcite- ‘to get caught in an avalanche’

- nevlugte- ‘to have clinging debris/lint/snow/dirt’

- nevluk ‘clinging debris’

- nutaryuk ‘fresh snow’

- pircir- ‘to blizzard’

- pir(e)t(e)pag- ‘to blizzard severely’

- pirrelvag- ‘to blizzard severely’

- pirta ‘blizzard, snowstorm’

- pirtuk ‘blizzard, snowstorm’

- qanikcaq ‘snow on ground’

- qanikcir- ‘to get snow on ground’

- qanir- ‘to snow’

- qanisqineq ‘snow floating on water’

- qanugglir- ‘to snow’

- qanuk ‘snowflake’

- qanunge- ‘to snow’

- qengaruk ‘snow bank’

- qerretrar- ‘for snow to crust’

- qetrar- ‘for snow to crust’

- utvak ‘snow carved in block’

Yet he notes at least 23 snow-related terms in English, too. When framed this way, Yup’ik doesn’t seem quite so exotic:

- avalanche

- blizzard

- blowing snow

- dusting

- flurry

- frost

- hail

- hardpack

- ice lens

- igloo (from Inuit *iglu ‘*house’)

- pingo (from Inuit *pingu(q) ‘*ice lens’)

- powder

- sleet

- slush

- snow

- snow bank

- snow cornice

- snow fort

- snow house

- snow man

- snow-mixed-with-rain?

- snowflake

- snowstorm

You can read Woodbury’s entire post for more details here:

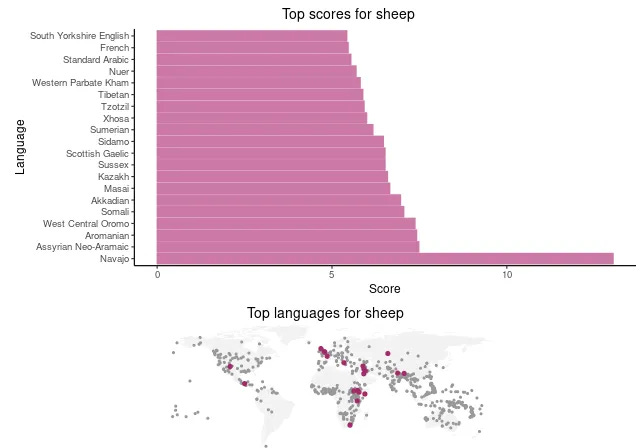

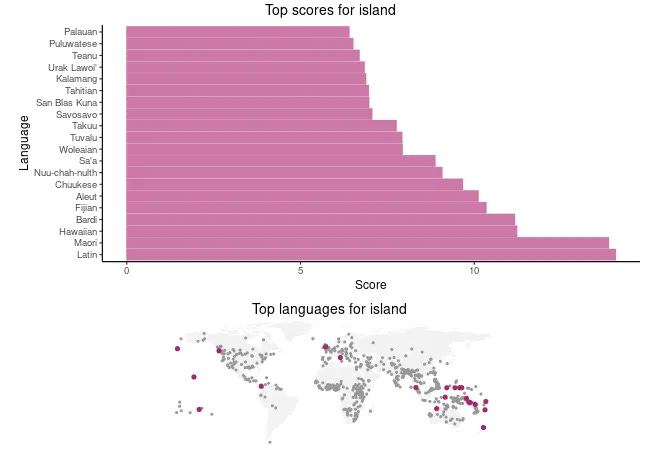

Now, enter a new study which claims that having a greater abundance of words for snow is indeed characteristic of Inuit languages. Using a dataset of 1,574 bilingual dictionaries where one of the two languages is English, a team of researchers led by Temuulen Khishigsuren examined 616 languages to determine which semantic domains are overrepresented in the vocabulary of each language. When looking at words having to do with horses, the researchers looked at not just words for horses themselves, such as Mongolian аргамаг argamag ‘a good racing or riding horse’, but at related words as well, such as Mongolian чөдөрлөх chödörlökh ‘to hobble a horse’.

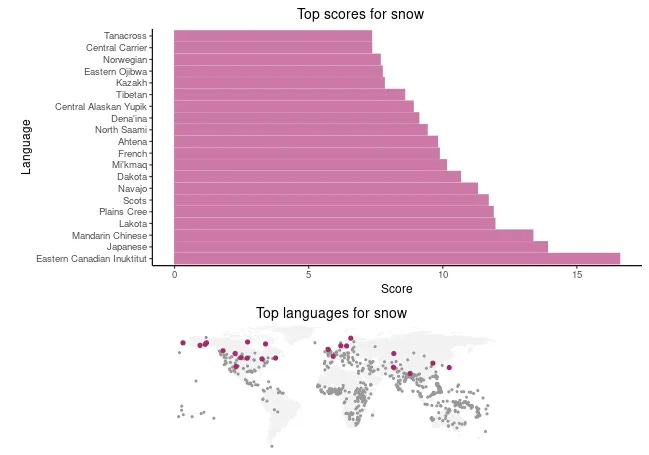

According to this dataset, Inuit and other circumpolar languages do indeed have more words for snow. All three of the Inuit languages in their dataset (Eastern Canadian Inuktitut, Western Canadian Inuktitut, and North Alaskan Inupiatun) appear in the top 20 languages for ‘snow’.

Since Khishigsuren et al.’s study is about the semantic domain of snow rather than specific words for snow, it makes sense that their methods result in a high lexical elaboration score for circumpolar languages. Their data include various terms that are snow-adjacent, so to speak. Similarly, it has been well established that Inuit and other circumpolar languages (Chukchi, Dena’ina Athabascan, Sámi, etc.) have tremendously large vocabularies in the domain of sea ice as well (Krupnik 2017).

(Check out this incredible Sea Ice Atlas and this discussion of terminology for more examples of sea ice terminology.)

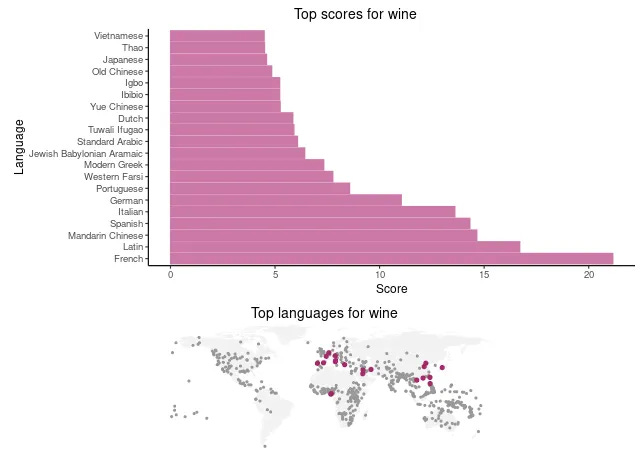

Other unsurprising results appear for other languages as well: the top scores for wine, for example, include French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese—languages spoken in some of the world’s largest wine-exporting regions. (But third on that list is Mandarin Chinese, and in the top twenty are Igbo and Vietnamese, none of which have a strong geographic association with wine.) Another unsurprising result is that Navajo scores nearly double for sheep words than the next-closest language. (Sheep are indeed very important to Navajo culture.) And languages that score highly for ‘island’ (Māori, Hawaiian, Aleut, Nuuchahnulth, Tuvalu, etc.) are located in insular regions, as expected.

What can we learn from elaborate vocabularies?

Now, it may be tempting to dismiss this study as boring for the reasons I mentioned above (“Languages have words for the stuff people do or use a lot. Duh.”), but this study contributes more than just that. It’s important for me as a linguistics communicator to combat fallacious ideas like linguistic determinism and not give additional credence to beliefs that exoticize indigenous peoples, but having made those caveats, we can better appreciate what this study does accomplish.

Linguists use the term semantic domain or semantic field to refer to the abstract conceptual space covering a particular group of meanings. For example, linguists talk about the “temperature domain”, the variety of ways languages express temperature concepts (Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2015); or they talk about the “ingestion domain” or “gustatory domain”, referring to ways that languages express concepts relating to eating and drinking (Newman 2009). This new study coins the term lexical elaboration to refer to the number of lexemes (dictionary entries) in a language that are related to a concept (Khishigsuren et al. 2025: 1)—in other words, how many words there are for a particular semantic domain.

Historically, finding languages with elaborate lexicons for one domain or another was a manual and somewhat subjective task—linguists would simply make lists of words for domains that caught their attention, and impressionistically compare them to other languages. This is unfortunate because we can actually learn a great deal about how language works from lexical elaboration. There’s a 1,000-page volume devoted solely to the linguistics of temperature, for example, which explores ways that temperature terms give rise to certain function words, or how antonyms and scalar terms work in the temperature domain, among many other topics (Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2015). Languages which are more strongly lexically elaborated for temperature can yield important insights.

What Khishigsuren et al.’s study does is provide a method for potentially identifying other lexically elaborate domains in a language, which linguists might have overlooked in the past. For example, they end the paper by pointing out that terms relating to dancing have previously received little attention; however, their dataset suggests a few languages in which dancing might be lexically elaborated, pointing to new areas of research for linguists who work with those languages.

Overall, it’s a novel study with potential for practical use, but one which requires a little more nuance to appreciate than it has been given by media outlets.

If you’d like to explore lexical elaboration in different languages yourself, the authors have made available a handy online tool, which is how I produced the visuals above:

The authors also have an article in The Conversation explaining their findings and talking about Inuit words for snow:

They rightly end the article by urging readers not to read too far into their results:

Most importantly, our results run the risk of perpetuating potentially harmful stereotypes if taken at face value. So we urge caution and respect while using the tool. The concepts it lists for any given language provide, at best, a crude reflection of the cultures associated with that language.

You can also read the original research article here:

- Khishigsuren et al. 2025. A computational analysis of lexical elaboration across languages. PNAS 122(15). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2417304122

Further reporting is here:

🙏 Credits

This issue of the Linguistic Discovery newsletter was edited by Amy Treber. If you’re looking for professional copyediting services, email Amy at amytreberedits@gmail.com.

The final responsibility for any mistakes or omissions is of course still wholly my own.

📚 Recommended Reading

📑 References

- Boas, Franz. 1911. Introduction. In Handbook of American Indian languages, Part 1 (Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletins 40), 1–84. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Chen, M. Keith. 2013. The effect of language on economic behavior: Evidence from savings rates, health behaviors, and retirement assets. American Economic Review 103(2). 690–731. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.2.690.

- Crystal, David & Alan C.L. Yu. 2024. A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. 7th edn. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Heyes, Scott A. 2011. Cracks in the knowledge: Sea ice terms in Kangiqsualujjuaq, Nunavik. Canadian Geographies / Géographies canadiennes 55(1). 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2010.00346.x.

- Hill, Archibald A. 1952. A note on primitive languages. International Journal of American Linguistics 18(3). 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1086/464167.

- Jacobson, Steven A. (ed.). 1984. Yup’ik Eskimo dictionary. Fairbanks: Alaska Native Language Center.

- Khishigsuren, Temuulen, Terry Regier, Ekaterina Vylomova & Charles Kemp. 2025. A computational analysis of lexical elaboration across languages. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122(15). e2417304122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2417304122.

- Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria (ed.). 2015. The linguistics of temperature (Typological Studies in Language 107). John Benjamins.

- Krupnik, Igor. 2017. ‘How many Eskimo words for ice?’ Collecting Inuit sea ice terminologies in the International Polar Year 2007–2008. Canadian Geographies / Géographies canadiennes 55(1). 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2010.00345.x.

- Malotki, Ekkehart. 1983. Hopi time: A linguistic analysis of the temporal concepts in the Hopi language (Trends in Linguistics: Studies & Monographs 20). Berlin: Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110822816.

- Martin, Laura. 1986. Eskimo words for snow: A case study in the genesis and decay of an anthropological example. American Anthropologist 88(2). 418–423.

- Matthews, P. H. 2014. The concise Oxford dictionary of linguistics (Oxford Paperback Reference). 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Newman, John (ed.). 2009. The linguistics of eating and drinking (Typological Studies in Language v. 84). Amsterdam ; Philadelphia: John Benjamins Pub. Co.

- Payne, Thomas E. 2011. Understanding English grammar: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Pullum, Geoffrey K. 1989. The great Eskimo vocabulary hoax. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 7(2). 275–281.

- Roberts, Seán G., James Winters & Keith Chen. 2015. Future tense and economic decisions: Controlling for cultural evolution. (Ed.) Ramesh Balasubramaniam. PLOS One 10(7). e0132145. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132145.

- Thalbitzer, William. 1911. Eskimo. In Handbook of American Indian languages, Part 1 (Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletins 40), 967–1069. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Ullmann, Stephen. 1951. Words and their use. New York: Hawthorn Books.

- Whorf, Benjamin Lee. 1950. An American Indian model of the universe. International Journal of American Linguistics 16(2). 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1086/464066.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.