Why do languages change? The linguistics of “The Iron Dreamers”, Part 1

Could a language stay frozen in time?

At some point in the perhaps not too distant future, humanity will solve the problem of mortality. We will either halt the process of aging, or life expectancy will start to increase at a rate greater than one year per year, at which point humans essentially become immortal. (Life expectancy currently increases at a rate of about one year every four years.)

You may be among the last generations to die of natural causes.

In a post-mortem world where humans are immortal, what will happen to the languages we speak?

Science communicator Ashley Christine (@ModernDayEratosthenes: TikTok | Instagram | YouTube | Website) explores this exact question as part of her debut sci-fi novel, The Iron Dreamers, and today we’re going to talk about the linguistics of immortality.

It was only a matter of time until humanity stumbled upon the key to life—whether intentionally or by accident. ~ Iron Dreamers, p. 85

- Part 1: Why do languages change? (this article)

- Part 2: Are we stuck with the same grammar for life?

- Part 3: Are some languages more complex than others?

- Part 4: How are new languages created?

We learn early in the book that a portion of humanity has become immortal and fled to space, where they establish a colony of several hundred thousand people on a space station called Sol. However, these immortals have also become infertile, so no new children are born to this community. After a thousand years, the people are still speaking 21st-century English, and have also created a sign language called Sessiz (derived from the Turkish word sessizlik ‘silence’).

Why hasn’t English changed in all that time? One of the characters in the book explains:

“I thought language would have changed by now,” she says.

“It should have changed. If we lived and died as humans used to, then even English would have evolved to be unrecognizable to you. But everyone here was born in the twenty-first century[.] There’s been no reason for language to change.” (p. 193)

So how realistic is this? Could a language really stay largely unchanged for 1,000 years, even if its speakers were immortal and no new children were acquiring the language? Let’s find out!

How much do languages change over time?

The idea of an unchanging language frozen in time is pure myth.

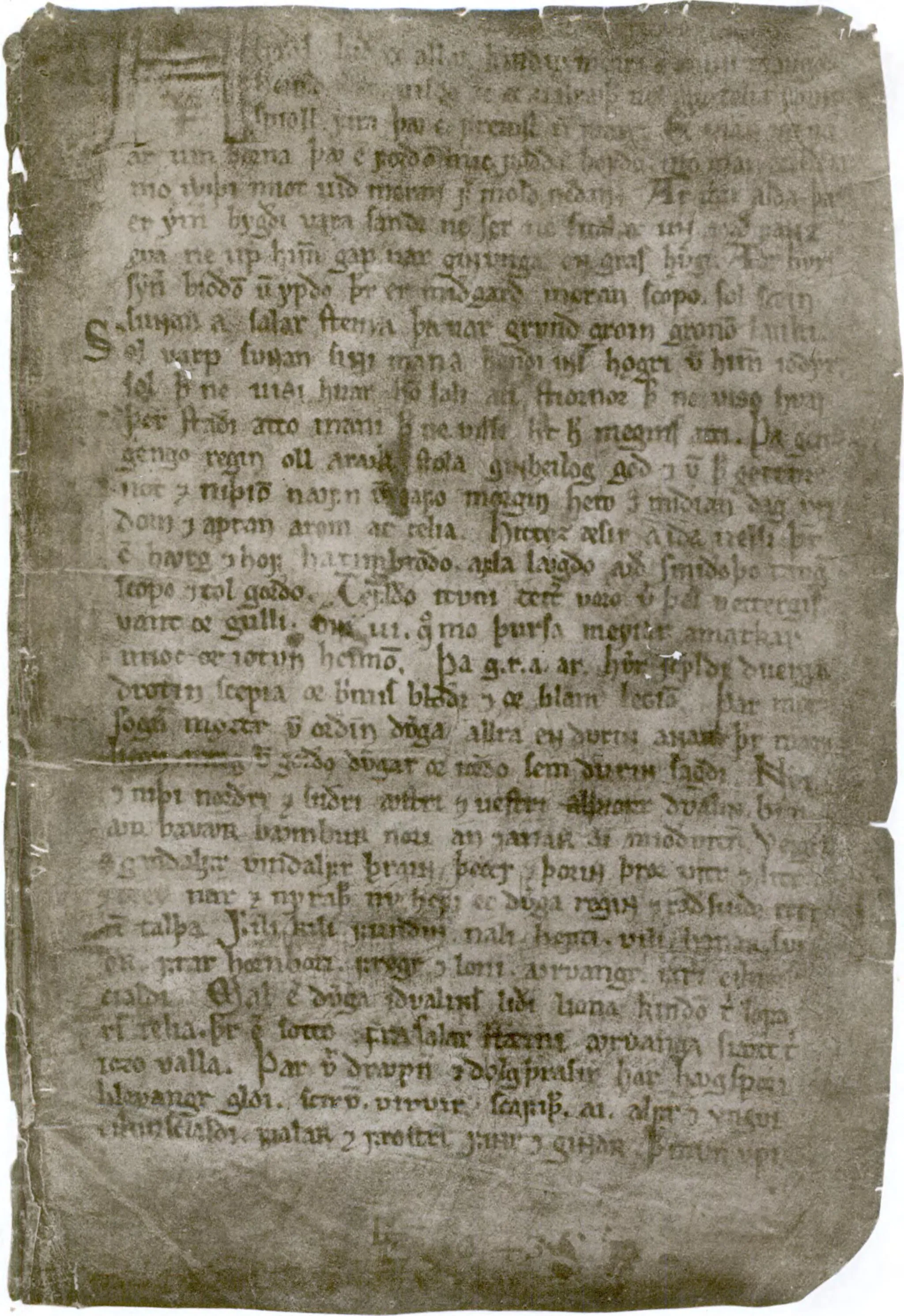

All languages—or at least the ones spoken by us mere mortals—are constantly changing (a fact which grammar pedants find incredibly distressing). The idea of an unchanging language frozen in time is pure myth. For example, it’s often said that the Old Icelandic sagas, written in the 1200s, are still understandable to Modern Icelandic speakers today. This is actually a linguistic illusion. For starters, the original manuscripts are most definitely not readable without training, as you can see in the image below.

To make them legible, modern editions of the sagas are rewritten in the modern, standardized Icelandic orthography (writing system). This orthography ignores phonetic distinctions which were present in Old Icelandic but have since been lost in the modern language, such as nasal vs. oral vowels, and distinctions between the vowels /ɛ/ and /e/ or the vowels /œ/ and /ø/. Old Icelandic also had much freer word order and different syntactic rules than Modern Icelandic, and the meanings of many words have shifted drastically. It’s deceptively easy to read a sanitized version of the sagas and assume you’ve got the pronunciation right and understand all the meanings correctly, when in fact you likely have many details wrong.

Even though the centuries did change Icelandic, those changes are dwarfed (pun intended) by what happened to English. Here’s a comparison of the Lord’s Prayer in Old English (spoken up until ca. 1066) vs. Modern English (from roughly the early 1600s onwards).

Old English

Fæder ūre þū þē eart on heofonum

Sī þīn nama gehālgod

Tō becume þīn rice

Gewurþe þīn willa

On erðon swā swā on heofonum

Urne gedæghwamlīcan hlāf syle ūs tō dæg

And forgyf ūs ūre gyltas

Swā swā wē forgyfð ūrum gyltendum.

And ne gelæd þū ūs on costnunge

Ac alȳs ūs of yfele.

Modern English

Our Father in heaven,

hallowed be your name.

Your kingdom come.

Your will be done,

on earth as it is in heaven.

Give us this day our daily bread.

And forgive us our debts,

as we also have forgiven our debtors.

And do not bring us to the time of trial,

but rescue us from the evil one.

The differences between these two versions of the prayer are not just differences in pronunciations and meanings. Nearly the entire grammar of English has been reworked. For example, Old English lacked a future tense. To express future actions, the verb bēon ‘to be’ was used instead. The Modern English future auxiliary will evolved from the Old English verb willan, which meant ‘to want, desire’ (Aijmer 1985). (The noun form of willan was willa ‘will’, which you can see in line 4 of the Old English version of the Lord’s Prayer above, and which became the Modern English noun will.) This process by which content words like willan ‘want’ become grammatical function words like will ‘FUTURE’ is called grammaticalization, and it’s a process that’s in constant operation in every language, perpetually wearing down content words and turning them into grammatical words, prefixes, or suffixes.

Old English verbs also had extensive conjugations and nouns had extensive declensions:

| Present | Past | |

|---|---|---|

| Infinitive | dǣlan | (tō) dǣlenne |

| Indicative | ||

| 1sg. | dǣle | dǣlde |

| 2sg. | dǣlst | dǣldest |

| 3sg. | dǣlþ | dǣlde |

| pl. | dǣlaþ | dǣldon |

| Subjunctive | ||

| sg. | dǣle | dǣlde |

| pl. | dǣlen | dǣlden |

| Imperative | ||

| sg. | dǣl | |

| pl. | dǣlaþ | |

| Participle | ||

| dǣlende | (ġe)dǣled |

Figure 2. Conjugation of dǣlan ‘to share’ in Old English (Wikipedia: Old English grammar)

| Case | Masculine | Neuter | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | Singular | Plural | |

| Nominative−Accusative | hund | hundas | sċip | sċipu |

| Genitive | hundes | hunda | sċipes | sċipa |

| Dative | hunde | hundum | sċipe | sċipum |

Figure 3. Declension of hund ‘dog’, and sċip ‘boat’ in Old English (Wikipedia: Old English grammar)

If 1,000 years is enough to so dramatically overhaul the grammar of English, why should we believe that the language of Sol in Iron Dreamers—which also had a millennium to metamorphosize—wouldn’t change as well?

It’s because of one important aspect of the worldbuilding in Iron Dreamers: the fact that the people of Sol are infertile. Children learning their first language is the primary driver of language change, because children inevitably come to slightly different inferences about the words and rules of their language than their parents did. For any given generation, most of the grammatical rules and word meanings stay the same, but not all of them. With successive generations, enough changes accrete until the language transforms entirely.

It’s also generally assumed among linguists that after one’s teenage years, the grammar of your first language stays stable over the course of your lifetime (even while your vocabulary continues to grow). Adults are not thought to contribute in a meaningful way to language change over time. All the change happens during the process of children acquiring the language—or so we thought. We’ll look at some research challenging this assumption in the next post in this series.

So the narrative premise that Sol citizens are infertile makes the idea of a static language credible because Sol society lacks the most pivotal component of language change—intergenerational transmission; that is, passing language from one generation to the next via cultural transmission.

But does that mean the Sol language wouldn’t change at all? Not likely! Even without intergenerational transmission, there are manifold forces at work shaping language.

How does vocabulary change over time?

The median person knows 6,200 more words at age 60 than at age 20.

The most obvious of these is vocabulary change. New technologies lead to new vocabulary, both for the technology itself and for the new experiences they create. Merriam-Webster added the terms shadowban and touch grass to their dictionary in 2024 (Merriam-Webster), terms that are not about technology itself but ones that only make sense in the context of social media technologies.

Technology can also shift the usage of existing words. The Latin word carrus originally referred to a wagon or cart (and was itself borrowed from the Gaulish word *karros ‘two-wheeled Celtic war chariot’), but by the time of Old French the word carre referred to any wheeled vehicle. English then borrowed the word, and in the 1800s U.S. car referred primarily to the cars of trains or streetcars. It then shifted its meaning to ‘automobile’ in the early 1900s.

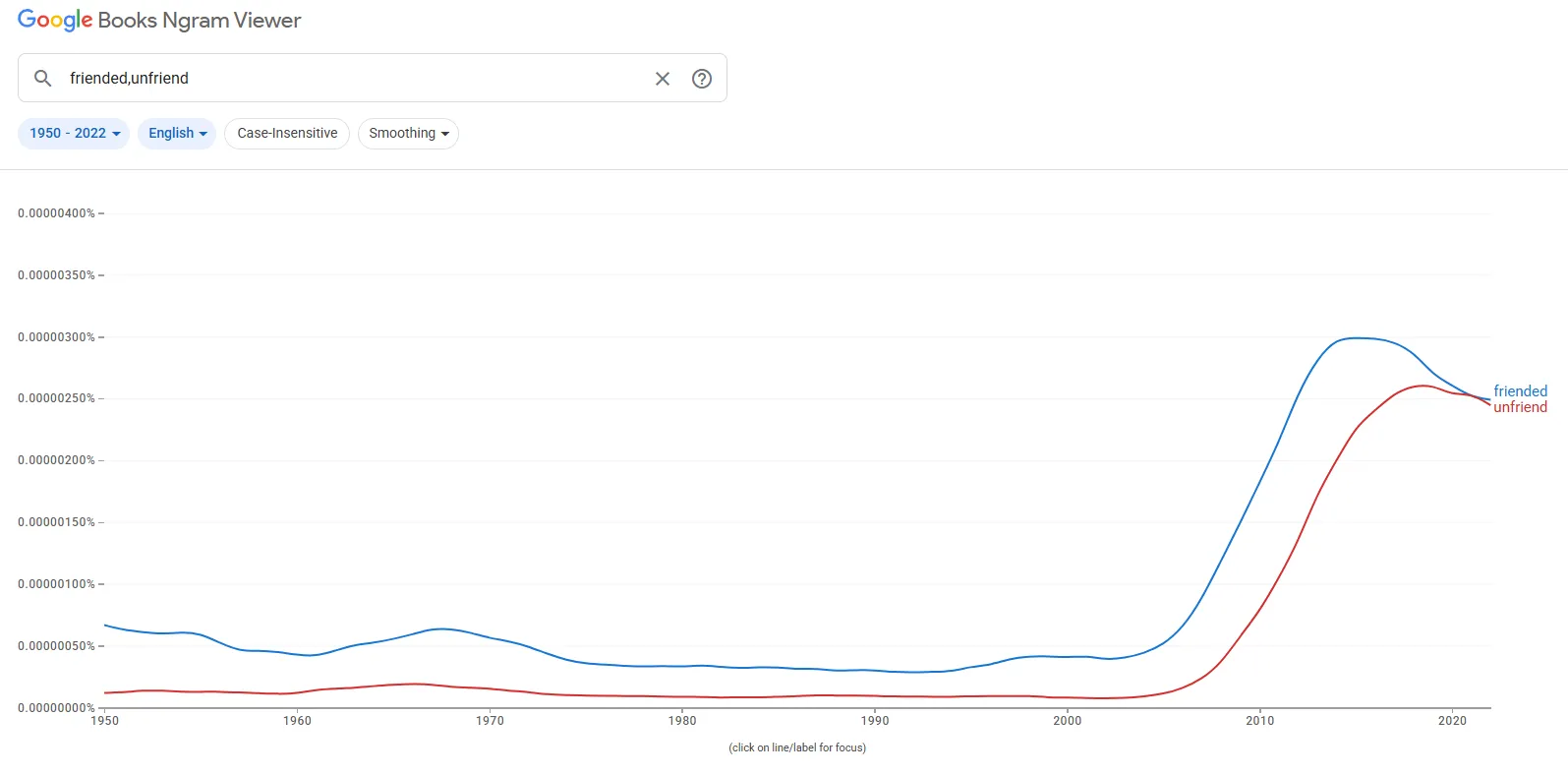

Another example is the verb to friend. Prior to the mid-00’s, friend did not have a canonical usage as a verb. The verb form of the word was befriend. But the advent of social media changed that, so that friend could mean specifically ‘add someone to one’s social media network’—a distinct meaning from befriend.

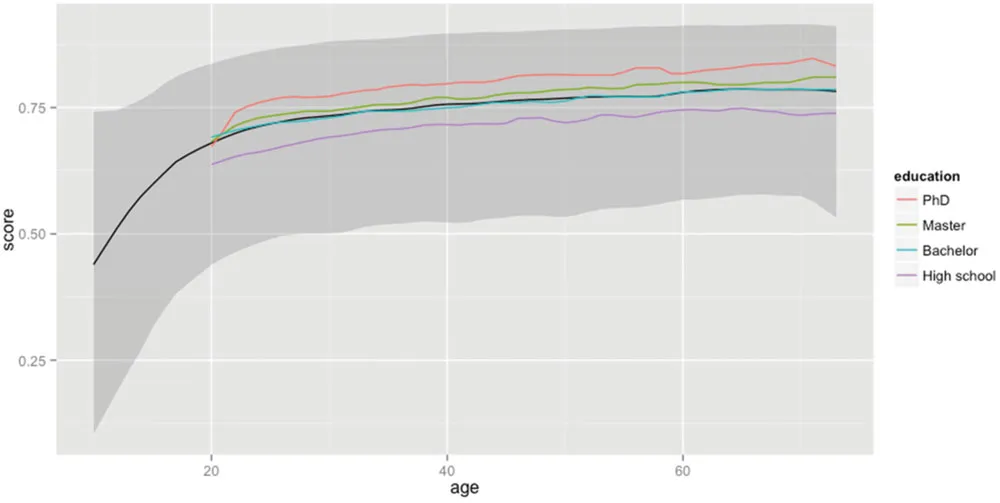

In addition to creating new vocabulary, adults continue to learn more of the existing vocabulary of their language throughout their lifetimes. The graph below shows the percentage of words in an experimental list that are known by people of different ages and education levels.

The following table shows the estimated number of words known by 20-year-olds and 60-year-olds, as well as the high end and low end of the vocabulary range at each age. The median person knows 6,200 more words at age 60 than at age 20.

| Age | Low End | Median | High End |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 27,100 | 42,000 | 51,700 |

| 60 | 35,100 | 48,200 | 56,400 |

Figure 6. Estimates of the lemmas (words) known by 20-year-olds and 60-year-olds (Brysbaert et al. 2016)

Linguistic accommodation

Long-term exposure to another dialect does gradually affect your own pronunciation, often without you realizing it.

Another language change that happens among adults is adapting the way you speak to the people you interact with regularly—a phenomenon known as linguistic accommodation, or, when referring to pronunciation specifically, accent accommodation. Not only do most people do this on a conversation-by-conversation basis, but people with extended exposure to a different accent or dialect will gradually accommodate that way of speaking as well. If you grew up in one dialect region and then moved to another in early adulthood, it’s very likely that you’ll revert to your original dialect when you call your family back home. On the other hand, long-term exposure to another dialect does gradually affect your own pronunciation, often without you realizing it. People who move from one English-speaking country to another are often shocked when, after several years, their friends in their home country tell them they’ve picked up an accent.

A neat thing about the linguistic worldbuilding in Iron Dreamers is that Christine recognizes the existence of accent accommodation and incorporates it. The citizens of Sol come from countries all over the world, so you would expect there to be a great deal of accent accommodation happening as they all settle on a particular dialect of English. This seems to be exactly what has happened in the book:

Their accents are predominantly American, but there’s a hint of something else—British or Swedish or something—as if they had moved to another other country and their accent assimilated after years of exposure. (p. 45)

Neither of the changes mentioned above—shifts in vocabulary or shifts in pronunciation—require intergenerational transmission. So even though the citizens of Sol aren’t passing their language on to anyone new, we’d still expect there to be significant changes in vocabulary and pronunciation after 1,000 years: many new terms, other terms having fallen out of use, other terms having radically shifted their meanings, and notable shifts in pronunciation.

Yet ultimately those changes might not cause too much of a headache to a time traveler from 1,000 years past—perhaps no more difficulty than learning a highly divergent dialect. Where things get really tricky is grammatical changes—differences in the rules of the language itself. Can adults alone change the grammar of a language? Or does significant grammatical change require intergenerational transmission as children learn the language?

A growing body of evidence suggests that one’s grammar is not as stable over the lifetime as we previously thought. So in the next issue of this 4-part series, we’ll explore just how much your grammar can change in adulthood, and what that means for the citizens of Sol.

Thanks for reading! If you’re a paid subscriber, jump to the bottom of this article for a fun parallel between The Iron Dreamers and the French Academy. ⬇️

ℹ️ Articles in this series

- Part 1: Why do languages change? (this article)

- Part 2: Are we stuck with the same grammar for life?

- Part 3: Are some languages more complex than others?

- Part 4: How are new languages created?

📑 References

- Aijmer, Karin. 1985. The semantic development of will. In Jacek Fisiak (ed.), Historical semantics and historical word-formation (Trends in Linguistics: Studies & Monographs 29), 11–22. de Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110850178.11.

- Brysbaert, Marc, Michaël Stevens, Paweł Mandera & Emmanuel Keuleers. 2016. How many words do we know? Practical estimates of vocabulary size dependent on word definition, the degree of language input and the participant’s age. Frontiers in Psychology 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01116.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.

🌟 Bonus Content

Here’s a fun little parallel between The Iron Dreamers and the French Academy: