Are we stuck with the same grammar for life? The linguistics of “The Iron Dreamers”, Part 2

How does your grammar change over the course of your lifetime?

Grammatical changes over the lifespan aren’t always linear. There’s also evidence for a “rollercoaster effect”, where a linguistic feature will undergo drastic swings in frequency at different life stages.

For most of modern linguistics history, linguists assumed that once children pass the prime language-learning age—known as the critical period—their grammar is fixed for life. People learn new vocabulary throughout their lives, and their accents may change as their social networks shift, but it was assumed that they continue using the same grammatical rules. Language only changes from one generation to the next because children in their callowness inevitably learn slightly different grammatical rules than the generation before them. All the action of language change happens during the process of acquiring one’s first language—or so we thought.

But what if you encounter a new grammatical construction a sufficiently large number of times as an adult? Is that enough to change your grammar? Or are you locked into the grammar of your idiolect—your own personal dialect—for life? What if you lived longer than a normal human—say, 1,000 years? Would that be long enough for your grammar to change completely?

This is exactly the question that arises in science communicator Ashley Christine’s (@ModernDayEratosthenes) debut sci-fi novel, The Iron Dreamers. In a world where humans are immortal, would their grammar change over time? In today’s issue of the newsletter, we’ll talk about the linguistics of immortality in The Iron Dreamers.

- Part 1: Why do languages change?

- Part 2: Are we stuck with the same grammar for life? (this article)

- Part 3: Are some languages more complex than others?

- Part 4: How are new languages created?

To briefly recap the premise of The Iron Dreamers, we learn early in the book that a portion of humanity has become immortal and fled to space, where they establish a colony of several hundred thousand people on a space station called Sol. However, these immortals have also become infertile, so no new children are born to this community. After a thousand years, the people are still speaking 21st-century English.

Why hasn’t English changed in all that time? One of the characters in the book explains:

“I thought language would have changed by now,” she says.

“It should have changed. If we lived and died as humans used to, then even English would have evolved to be unrecognizable to you. But everyone here was born in the twenty-first century[.] There’s been no reason for language to change.” (p. 193)

So how realistic is this? Could a language really stay largely unchanged for 1,000 years, even if its speakers were immortal and no new children were acquiring the language? Let’s find out!

For some theoretical approaches to language change, frequency is everything. This is especially true of usage-based linguistics, which adopts the view that grammar is shaped by how we use and experience language (Diessel 2017; Bybee 2023). In a usage-based approach, the more you use a word, the more entrenched in your mind the word and its meaning become. At the same time, the most frequent words are also the ones that are most likely to undergo phonetic reduction, semantic bleaching, fossilization/routinization, and perhaps eventually grammaticalization. In this approach, frequency is the sine qua non of language change.

What we don’t know is whether these changes only happen during the process of learning a language as a child, or whether frequency continues to play a role in shaping the grammar of our idiolect as an adult. As one linguist put it in a review of the research on grammatical changes in adulthood:

Summarizing the state of the art, we conclude that next to nothing is known about lifespan changes affecting syntactic or grammaticalizing constructions that goes beyond exploratory or anecdotal evidence. (Anthonissen & Petré 2019: 1)

So it’s an open question whether the 1,000-year-old citizens of Sol in Iron Dreamers would be using different grammatical rules or still speaking 21st-century English.

Nonetheless, the most recent research suggests that individual idiolects can and do change over the lifespan. While the majority of research on lifespan changes focuses on phonetic and phonological changes to pronunciation (such as accent accommodation discussed above) (Anthonissen & Petré 2019: 3; Stevens 2025), there are a few studies that have looked explicitly at grammatical change.

Logically and empirically, there are ways that a speaker might react to a new grammatical construction making its way into a language (imagine Middle English speakers when future tense will first started appearing in the language) (Sankoff 2019):

- stable (most common): The speaker continues to speak the same way they always have. They may use the new construction sometimes, but the frequency with which they use it doesn’t change over time. This is what you’d expect in the absence of any social changes to the speaker’s life (Sankoff 2017: 299). If they don’t move regions, change their social networks, etc., there is no reason for them to adjust the way they speak.

- conservative (least common): In the face of novel linguistic changes, some speakers are reactionary and use the new construction less as they age.

- progressive (middlemost common): The speaker gradually increases their use of the new construction throughout their life.

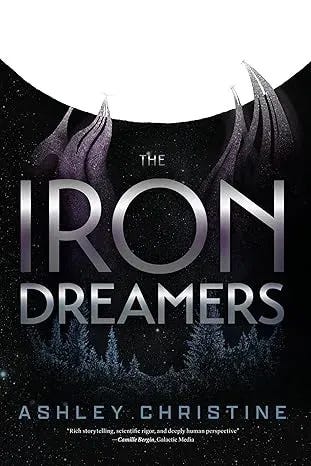

For example, one study looked at the emergence of constructions like X is said to be Y (called the nominative + infinitive construction, and labeled as “evidential” in the graphs below) over the lifespans of authors in the Early Modern English period (Anthonissen 2019). Author John Owen showed mostly stable use of the construction of his lifetime; authors John Milton and Roger L’Estrange showed progressive use over their lifetimes; and author Thomas Fuller showed a conservative trend, reducing his usage over time:

Another study of authors in the 1800s found that all of them increased their use of the present progressive (which was still new to the language at the time) or remained stable over the course of their writing career (Arnaud 1998). For instance, poet John Keats wrote a letter to his publisher John Taylor in 1818 describing a trip, and wrote “it rains” where today we would write “it is raining”, but otherwise he was a progressive user of the present progressive, with a very high frequency of usage.

However, grammatical changes over the lifespan aren’t always linear. There’s also evidence for a “rollercoaster effect” (Van Hofwegen & Wolfram 2010: 437), where a linguistic feature will undergo drastic swings in frequency at different life stages. One study looked at negative concord (often called “double negation”, although this is a bit of a misnomer) in four teenagers:

All four adolescents’ rates of negative concord were between 74% and 96%. By their mid to late twenties, three of them had dramatically reduced their use of negative concord. Leon, now an IBM executive, registered only 11%; his brother Russell, the proprietor of a hardware store, 36%; and Jojo, an army sergeant, 32%. Only Carlos, imprisoned for murder at the age of 20, retained the preponderant use of negative concord as an adult, at 88% (Sankoff 2017: 303, summarizing Baugh 1996: 411).

So it’s not so much that adults completely abandon old grammatical structures or fully embrace new ones. Instead, they merely shift the frequency with which they use older vs. newer constructions, all while still retaining the linguistic features from their youth (Raumolin-Brunberg 2005; Raumolin-Brunberg 2009; Raumolin‐Brunberg & Nurmi 2012; Anthonissen 2019).

Of course, the average human lifespan at present is only approximately 73.2 years (Our World in Data), so perhaps with more time we would indeed see certain grammatical features drop out of a person’s idiolect entirely—even the ones from their youth. Sol’s millennials (in the literal sense) in Iron Dreamers may have had enough time to cycle through a set of grammatical changes multiple times over.

Having established that it is possible for adults to change the grammar of their language over time even without intergenerational transmission, what types of changes might we expect for the isolated community of Sol? Would their language became simpler or more complex? We’ll answer that question in the next issue of this series!

ℹ️ Articles in this series

- Part 1: Why do languages change?

- Part 2: Are we stuck with the same grammar for life? (this article)

- Part 3: Are some languages more complex than others?

- Part 4: How are new languages created?

📑 References

- Anthonissen, Lynn. 2019. Constructional change across the lifespan: The nominative and infinitive in early modern writers. In Kristin Bech & Ruth Möhlig-Falke (eds.), Grammar – Discourse – Context: Grammar and usage in language variation and change (Discourse Patterns 23), 125–156. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110682564-005.

- Anthonissen, Lynn & Peter Petré. 2019. Grammaticalization and the linguistic individual: New avenues in lifespan research. Linguistics Vanguard. Walter de Gruyter GmbH 5(s2). https://doi.org/10.1515/lingvan-2018-0037.

- Arnaud, René. 1998. The development of the progressive in 19th century English: A quantitative survey. Language Variation & Change. Cambridge University Press (CUP) 10(2). 123–152. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394500001265.

- Baugh, John. 1996. Dimensions of a theory of econolinguistics. In Towards a social science of language: Papers in honor of William Labov, Vol. 1: Variation and change in language and society (Current Issues in Linguistic Theory 127), vol. 1, 397–420. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.127.24bau.

- Bybee, Joan. 2023. What is usage‐based linguistics? In The handbook of usage‐based linguistics (Blackwell Handbooks in Linguistics), 7–29. Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119839859.ch1.

- Diessel, Holger. 2017. Usage-based linguistics. In Mark Aronoff (ed.), Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199384655.013.363.

- Raumolin-Brunberg, Helena. 2005. Language change in adulthood: Historical letters as evidence. European Journal of English Studies. Informa UK Limited 9(1). 37–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825570500068125.

- Raumolin-Brunberg, Helena. 2009. Lifespan changes in the language of three early modern gentlemen. In Arja Nurmi, Minna Nevala & Minna Palander-Collin (eds.), The language of daily life in England (1400–1800) (Pragmatics & Beyond New Series 183), 165–196. John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/pbns.183.10rau.

- Raumolin‐Brunberg, Helena & Arja Nurmi. 2012. Grammaticalization and language change in the individual. In Heiko Narrog & Bernd Heine (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Grammaticalization (Oxford Handbooks in Linguistics), 251–262. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199586783.013.0020.

- Sankoff, Gillian. 2017. Language change across the lifespan. Annual Review of Linguistics 4. 297–316. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011817-045438.

- Sankoff, Gillian. 2019. Language change across the lifespan: Three trajectory types. Language 95(2). 197–229.

- Stevens, Mary. 2025. Sound change proceeds incrementally within adult lifespans: Real-time evidence from/s/-retraction in Australian English. Language 101(3). 500–523. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2025.a969616.

- Van Hofwegen, Janneke & Walt Wolfram. 2010. Coming of age in African American English: A longitudinal study. Journal of Sociolinguistics 14(4). 427–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2010.00452.x.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.