Are some languages more complex than others? The linguistics of “The Iron Dreamers”, Part 3

Do languages get simpler over time? Could they get more complex?

All languages are equally capable of accomplishing any communicative tasks that humans need them for. There is no concept that can be expressed in one language but not another; there is no language that is incapable of discussing higher-order mathematics and science; there is no language that allows you to think more clearly than any other. All languages adapt to the needs of their speakers.

Do certain types of societies give rise to certain types of languages? Do isolated communities have more complex languages? What about smaller communities? Can languages become more or less complex over time?

Today we’ll explore the effects of community size and isolation on language complexity as we look at the linguistics of science communicator Ashley Christine’s (@ModernDayEratosthenes) debut sci-fi novel, The Iron Dreamers.

- Part 1: Why do languages change?

- Part 2: Are we stuck with the same grammar for life?

- Part 3: Are some languages more complex than others? (this article)

- Part 4: How are new languages created?

To briefly recap the premise of The Iron Dreamers, we learn early in the book that a portion of humanity has become immortal and fled to space, where they establish a colony of several hundred thousand people on a space station called Sol. However, these immortals have also become infertile, so no new children are born to this community. After a thousand years, the people are still speaking 21st-century English.

Why hasn’t English changed in all that time? One of the characters in the book explains:

“I thought language would have changed by now,” she says.

“It should have changed. If we lived and died as humans used to, then even English would have evolved to be unrecognizable to you. But everyone here was born in the twenty-first century[.] There’s been no reason for language to change.” (p. 193)

But given that Sol is a completely isolated community, would this affect how the language worked over 1,000 years? Let’s find out!

Are some languages more complex than others?

“Simpler” languages were viewed as primitive, less developed, and reflective of mental or racial inferiority. Language was used to retroactively justify and rationalize all sorts of preexisting beliefs denigrating other cultures.

Linguists have long had the impression that the languages of small hunter-gatherer communities are more complex than the languages of large trade languages like English or Mandarin. Here’s the kind of complexity I’m talking about:

-

Central Alaskan Yup’ik (Inuit–Yupik–Unangan; Alaska)

- tuntussuqatarniksaitengqiggtuqtuntu‑ssur‑qatar‑ni‑ksaite‑ngqiggte‑uqreindeer‑hunt‑fut‑say‑neg‑again‑3sg:ind

‘He had not yet said again that he was going to hunt reindeer.’

Payne (1997: 28)

-

Chitimacha (isolate; Louisiana)

- hihiand

- nikincukingni‑kint‑cuy‑ki‑ngwater‑drop‑irr.sg‑1sg.agt‑deb

‘I'll have to drop you in the water.’

Swadesh (1939: A1c.2)

-

Mohawk (Iroquoian; Ontario, Quebec, New York)

Thaʼtontahohah(ah)iiakonhátieʼ.

- thaʼ‑t‑onta‑ho‑hah‑a‑hiiak‑on‑háti‑eʼcontr‑duact‑cisloc‑m.sg.pat‑road‑link‑cross‑stat‑prog‑stat

‘He was just weaving back and forth across the road.’

Mithun (2020: 943)

Linguistics uses a special format for presenting examples that allows anybody to read and understand the example, even if they don’t know the language. This format is called an interlinear gloss. The number of lines can vary, but they are usually something like the example below.

A list of glossing abbreviations can be found here.

| Line | Description |

|---|---|

| Central Alaskan Yup’ik (Inuit–Yupik–Unangan; Alaska) | A header with some language information, such as its family and where it is spoken |

| tuntussuqatarniksaitengqiggtuq | A transcription of the example in the language. |

| tuntu-ssur-qatar-ni-ksaite-ngqiggte-uq | A breakdown of the morphemes (meaningful parts like stems, prefixes, and suffixes) in each word. |

| reindeer-hunt-FUT-say-NEG-again-3SG:IND | The glosses (brief definitions) for each morpheme. Grammatical categories are glossed using Latinate technical terms and labeled in SMALL CAPS. The meanings of the abbreviations are usually provided in a footnote or table somewhere in the text. You can see the abbreviations used in Linguistic Discovery’s content here. |

| ‘He had not yet said again that he was going to hunt reindeer.’ | The translation for the example. |

| Payne (1997: 28) | The bibliographic source of the example. |

If you compare these examples to their English translations, you’ll see that these languages pack more meanings into a single word than English, and explicitly mark various grammatical distinctions (all the morphemes glossed in small caps) that English lacks.

But while we have an intuitive notion that languages like these are more complex than large international languages like Spanish or French, this has been difficult to prove in part because the notion of complexity is a slippery one. Entire volumes have been dedicated to defining the concept (Sampson, Gil & Trudgill 2009; McWhorter 2011; Trudgill 2011) and numerous papers besides.

Another impediment to research on linguistic complexity is that one of the foundational assumptions in linguistics for many decades has been the idea that all languages are equally complex (the Equicomplexity Hypothesis) and therefore languages do not become more simple or complex over time (the Invariance of Linguistic Complexity Hypothesis) (Sampson 2009: 1; Trudgill 2011: 16). In fact, linguists sometimes make concerted efforts to point this out in introductory textbooks or materials aimed at the broader public. This is because up until the work of anthropologist Franz Boas, “simpler” languages were viewed as primitive, less developed, and reflective of mental or racial inferiority (Graffi 2011: 28). Language was used to retroactively justify and rationalize all sorts of preexisting beliefs denigrating other cultures. So, understandably, linguists go out of their way to counter these pernicious myths.

But what linguists are really saying when they state that all languages are equally complex is just that all languages are equally capable of accomplishing any communicative tasks that humans need them for. There is no concept that can be expressed in one language but not another; there is no language that is incapable of discussing higher-order mathematics and science; there is no language that allows you to think more clearly than any other. All languages are complex-adaptive systems that operate on the same cognitive principles and adapt to the needs of their speakers.

Still, even acknowledging that all languages are equally cognitively sophisticated, there may be a meaningful sense in which some languages exhibit greater grammatical complexity, allowing us to compare languages in terms of their complexity without any sort of associated value judgments about the mental sophistication of their speakers. Recent research suggests that this is exactly the case: certain social and cultural factors do indeed seem to correlate with certain types of languages.

Why do languages get simpler over time?

In situations where many people are bilingual in both languages from a young age, languages tend to become more complex, because speakers will mix grammatical features of both languages.

For starters, languages with a high degree of contact with other languages, where adults are learning them as second languages, tend to simplify their grammars over time (Trudgill 2011: 15–20). This appears to be what happened with English, as wave after wave of speakers of other languages—first the Celts, then the Norse, then the Norman French, then the peoples of England’s colonies—influenced the language.

The reason for this grammatical simplification is that adults are bad language learners! They smooth out irregularities, don’t use grammatical affixes, and prefer analytic constructions over synthetic ones. English losing the majority of its verbal and nominal inflection is an excellent example of what happens when adults language learners influence a language over several generations. (See Part 1 of this series for examples of how English has changed over time in this regard.)

We can see how influence from English affected the Oklahoma dialect of the Cayuga language, an Iroquoian language which for historical reasons wound up dispersed across opposite sides of the Canadian-American border (Mithun 1989). In Ontario, Cayuga continued to be used in daily conversation by a community of speakers, whereas in Oklahoma the language fell out of use, and the few remaining speakers use it infrequently, speaking English instead. As a result, Oklahoma Cayuga has become more analytic under influence from English than Ontario Cayuga.

For example, Cayuga has a repetitive prefix s- as well as a word é:ʔ meaning ‘again’. Fluent Ontario speakers will prefer the prefix as in example (4), while Oklahoma speakers prefer the separate word whenever the verb gets too complex, as in (5).

-

Ontario Cayuga

- tǫsasatkahaté:nihDUACT-REP-2.SG-SEMIREFL-turn_around

‘turn back around; re-turn’

Mithun (1989: 248–249)

-

Oklahoma Cayuga

- teskḁa:té:niDUACT-2.SG.AGT-SEMIREFL-turn_around

- é:ʔagain

‘turn around again’

Mithun (1989: 248–249)

Similarly, while Ontario speakers will use a single word for adjectival descriptions (6), Oklahoma speakers will use separate noun and adjective words (7):

-

Ontario Cayuga

- kỏnǫhsowá:nęko‑ʔnǫhs‑owanęf.sg.pat‑onion‑large.stat

‘she has a big onion’

Mithun (1989: 250)

-

Oklahoma Cayuga

- kuwa:nę́k‑uwanen‑big.stat

- ʔnǫ́hsaʔʔnǫhs‑aʔonion‑nzr

‘the onion is big’

Mithun (1989: 250)

On the other hand, in situations where many people are bilingual in both languages from a young age, languages tend to become more complex, because speakers will mix grammatical features of both languages (Trudgill 2011: 34). This creates irregularities as well as adds new grammatical categories to languages that previously lacked them. The Chitimacha language, for example, developed a three-way sit/stand/lie distinction in its auxiliary verbs due to rampant bilingualism with Muskogean languages of the U.S. Southeast (Hieber 2019: 14).

In the world of Sol in The Iron Dreamers, the community seems to have decided on English as the communal language from an early stage. Since the citizens of Sol came from all over Earth, it’s likely that not all of them originally knew English, which means Sol exhibits the first type of contact scenario: lots of adults learning English as a second language. Unlike normal situations of contact, however, I don’t think we’d expect Sol English to simplify!

For starters, the reason adult language learning simplifies a language is because the children of those adults learn those simpler patterns, ensconcing them in the language. But on Sol there are no children. Secondly, English has already been subject to extensive adult language learning for centuries. While it could in theory still become grammatically simpler, there’s not much grammatical complexity left to lose at this point! So perhaps Sol English would lose the third person singular -s suffix on verbs (which has already happened in African American Vernacular English), or start using separate words or auxiliaries for past and present tense instead of the -ing and -ed suffixes (maybe I be play and I did play, or something similar). But given that the non–English-speaking citizens of Sol were probably in the minority and have had a long time to learn the language, it’s entirely plausible that they would have exerted little to no influence on the grammar of Sol English.

Why do languages get more complex over time?

The existence of megalanguages like English and Mandarin have skewed our idea of what counts as a “small” language. For the vast majority of human history, any given language only had anywhere from several hundred to several thousand speakers.

In fact, there’s reason to think that Sol English might actually get more complex over time. If contact with other languages leads to simplification, a corollary is that isolation might foster greater complexity (Trudgill 2011: Ch. 3), assuming the community is in a stable state of isolation for a sufficiently long period of time (Trudgill 2011: 95). This is certainly true for the citizens of Sol, who have been living in linguistic isolation for 1,000 years. Without outside influences eroding grammatical complexity, any new grammatical features would accrete over time.

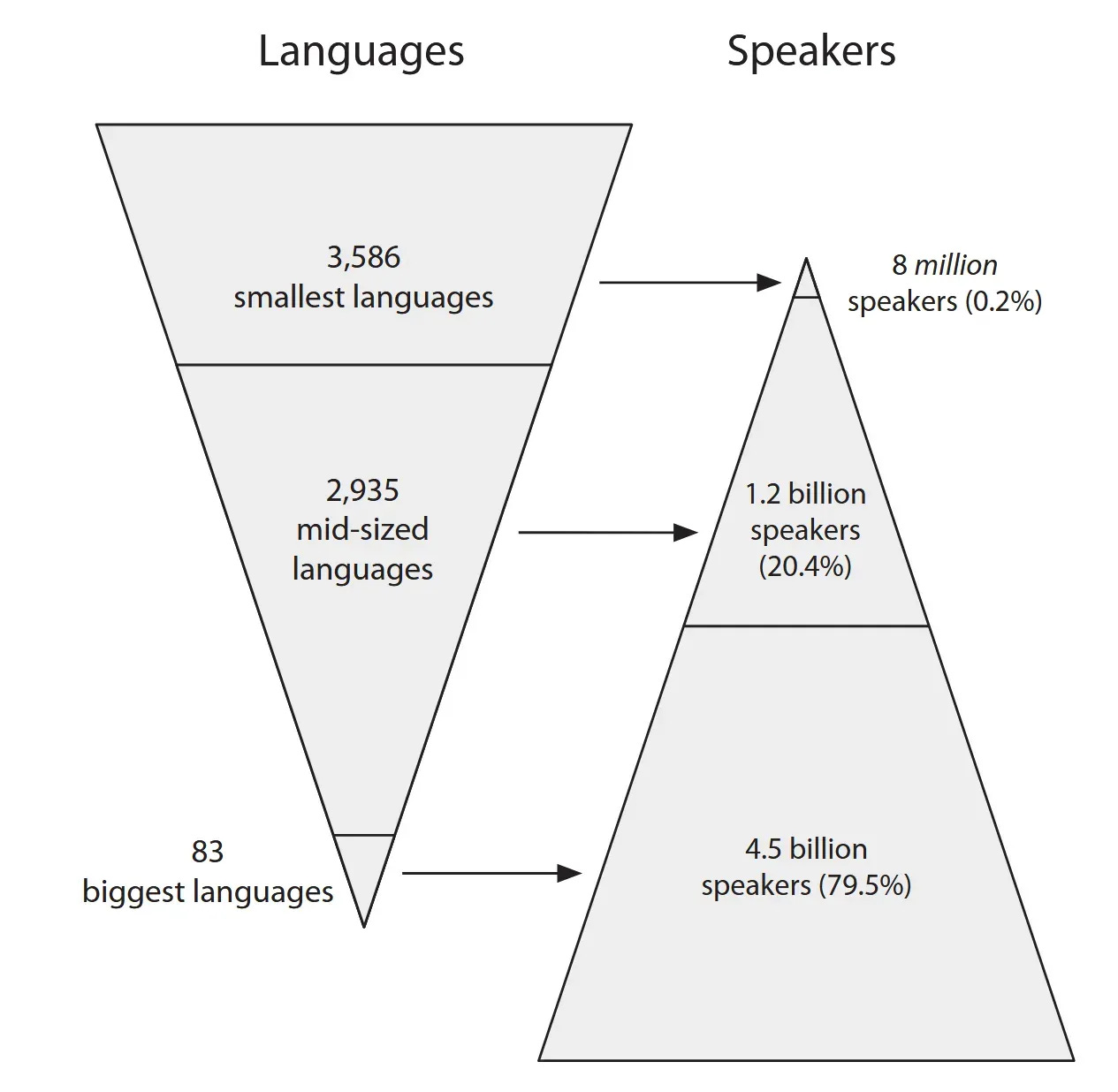

Additionally, we know that small languages (in the sense of having a small number of speakers) also tend to be more complex (Trudgill 2011: 99–104; Trudgill 2017; Reali, Chater & Christiansen 2018; Raviv, Meyer & Lev-Ari 2019). In population genetics, the effects of random change are greater when the population is small due to the statistics involved (Nettle 1999: 139). Language is similar. Small speaker sizes make it easier for otherwise complex features to take hold.

Consider for example that only 15 out of the 2,662 languages in the World Atlas of Language Structures have object-initial word order (Object-Subject-Verb or Object-Verb-Subject); languages of this type are exceedingly rare. Yet each one of these object-initial languages is small: a median speaker size of 750, as compared to 5,000 for the world’s languages as a whole (Nettle 1999: 139). Even though object-initial word order is thought to be non-optimal for efficient cognitive processing, the small size of these languages has made it possible for this grammatical rule to persist rather than vanish under selective cognitive pressures.

-

Hixkaryana (Cariban; Brazil)

- totoman

- yonoyehe-ate-him

- kamarajaguar

‘The jaguar ate the man.’

Derbyshire (1977: 593)

Another feature of societies that tends to preserve complexity is dense social networks (Trudgill 2011: 101–104; Mithun 2015: 37). In a community where everybody knows everybody, everyone shares the same social context. This reinforces existing linguistic conventions and creates greater linguistic cohesion. It doesn’t matter if certain forms are irregular or idiomatic, because everybody knows what you’re talking about.

However, the existence of megalanguages like English and Mandarin have skewed our idea of what counts as a “small” language. For the vast majority of human history, up until the Agrarian / Neolithic Revolution, any given language only had anywhere from several hundred to several thousand speakers. It wasn’t until the rise of sedentary societies and city-states with large urban populations that languages got big (Evans 2022: 10–13; Ostler 2005: 9–10; Janson 2012: 22; Trudgill 2011: 168–169). Even today, the median number of speakers for a language is only around 5,000 (Harrison 2007: 14). Fully half the world’s languages have fewer than 5,000 speakers.

Sol has a population of several hundred thousand immortals—actually quite large for a language by historical standards—so perhaps not the ideal circumstance for complexification.

On the other hand, there’s evidence in the book that the people of Sol share a lot of social context (not too surprising since they’ve been getting to know each other for 1,000 years)—so much so that they’ve developed a distaste for speaking too directly (pp. 52, 324). Overall, from my impression of the worldbuilding in the book, Sol does meet the other conditions that are favorable for complex languages (Trudgill 2011: 146; Trudgill 2017):

- low amounts of adult language contact

- high social stability

- small size

- dense social networks

- large amounts of communally-shared information

I think the situation on Sol could go either way, with Sol English either staying stable or gradually growing more complex over time. It’s certainly neat to imagine English becoming a polysynthetic language like Mohawk a thousand years from now!

But what if language change on Sol went even further? What if the mix of languages on Sol came together to form a new language altogether? In the next and final installment of this series, we’ll learn about the linguistics of pidgins and creoles, and how they might apply to The Iron Dreamers.

ℹ️ Articles in this series

- Part 1: Why do languages change?

- Part 2: Are we stuck with the same grammar for life?

- Part 3: Are some languages more complex than others? (this article)

- Part 4: How are new languages created?

📚 Recommended Reading

📑 References

- Derbyshire, Desmond C. 1977. Word order universals and the existence of OVS languages. Linguistic Inquiry 8(3). 590–599.

- Evans, Nicholas. 2022. Words of wonder: Endangered languages and what they tell us (The Language Library). 2nd edn. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Graffi, Giorgio. 2011. The pioneers of linguistic typology: From Gabelentz to Greenberg (Oxford Handbooks in Linguistics). (Ed.) Jae Jung Song. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199281251.013.0003.

- Harrison, K. David. 2007. When languages die: The extinction of the world’s languages and the erosion of human knowledge. Oxford University Press.

- Hieber, Daniel W. 2019. Semantic alignment in Chitimacha. International Journal of American Linguistics 85(3). 313–363. https://doi.org/10.1086/703239.

- Janson, Tore. 2012. The history of languages: An introduction (Oxford Textbooks in Linguistics). Oxford University Press.

- McWhorter, John H. 2011. Linguistic simplicity and complexity: Why do languages undress? (Language Contact & Bilingualism 1). De Gruyter Mouton.

- Mithun, Marianne. 1989. The incipient obsolescence of polysynthesis: Cayuga in Ontario and Oklahoma. In Nancy C. Dorian (ed.), Investigating obsolescence: Studies in language contraction and death (Studies in the Social and Cultural Foundations of Language 7), 243–258. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511620997.020.

- Mithun, Marianne. 2015. Morphological complexity and language contact in languages indigenous to North America. Linguistic Discovery 13(2). https://doi.org/10.1349/ps1.1537-0852.a.466.

- Mithun, Marianne. 2020. Grammaticalization and polysynthesis: Iroquoian. In Walter Bisang & Andrej Malchukov (eds.), Grammaticalization scenarios: Cross-linguistic variation and universal tendencies, Vol. 2: Grammaticalization scenarios from Africa, the Americas, and the Pacific (Comparative Handbooks of Linguistics 4.2), vol. 2, 943–976. De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110712735-008.

- Nettle, Daniel. 1999. Linguistic diversity. Oxford University Press.

- Ostler, Nicholas. 2005. Empires of the word: A language history of the world. Harper Collins.

- Payne, Thomas. 1997. Describing morphosyntax: A guide for field linguists. Cambridge University Press.

- Raviv, Limor, Antje Meyer & Shiri Lev-Ari. 2019. Larger communities create more systematic languages. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 286(1907). 20191262. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2019.1262.

- Reali, Florencia, Nick Chater & Morten H. Christiansen. 2018. Simpler grammar, larger vocabulary: How population size affects language. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285(1871). 20172586. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2586.

- Sampson, Geoffrey. 2009. A linguistic axiom challenged. In Geoffrey Sampson, David Gil & Peter Trudgill (eds.), Language Complexity as an Evolving Variable (Studies in the Evolution of Language 13), 1–18. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199545216.003.0001.

- Sampson, Geoffrey, David Gil & Peter Trudgill (eds.). 2009. Language complexity as an evolving variable (Studies in the Evolution of Language 13). Oxford University Press.

- Swadesh, Morris (ed.). 1939. Chitimacha texts. In Chitimacha grammar, texts, and vocabulary (American Council of Learned Societies Committee on Native American Languages Mss. 497.3.B63c G6.5). Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society Library.

- Trudgill, Peter. 2011. Sociolinguistic typology: Social determinants of linguistic complexity. Oxford University Press.

- Trudgill, Peter. 2017. The anthropological setting of polysynthesis. In Michael Fortescue, Marianne Mithun & Nicholas Evans (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Polysynthesis, 186–202. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199683208.013.13.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.