Did Kanzi the bonobo understand language?

Kanzi the bonobo, who learned language, made stone tools, and played Minecraft, dies at age 44. What can his remarkable linguistic abilities teach us about language?

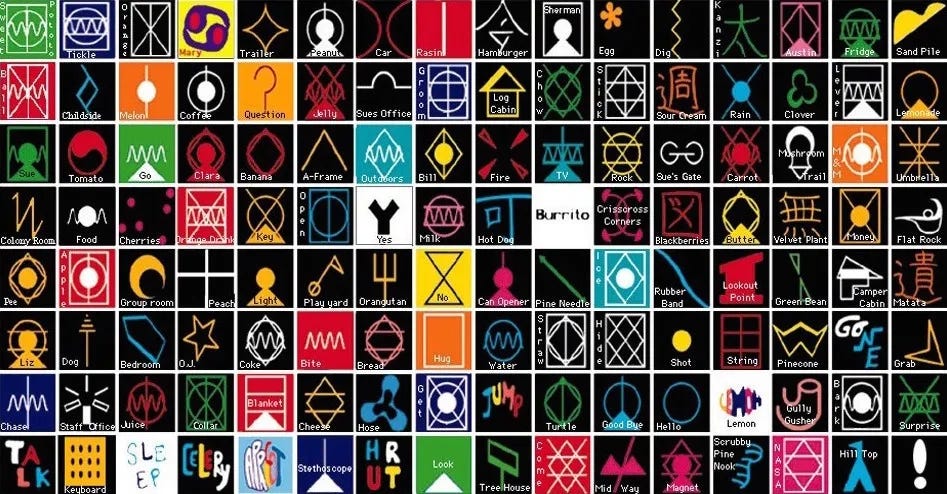

In the early 1980s, a team of researchers led by Sue Savage-Rumbaugh at Emory University’s Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center were struggling to teach a bonobo named Matata how to use a symbolic picture system called Yerkish to communicate. Each symbol, called a lexigram, represented one concept or object. Matata, who had been born in the wild, never really picked up on what the researchers were trying to teach her.

Unbeknownst to the researchers, however, someone else had apparently been paying attention to Matata’s lessons—her adopted son Kanzi, who had been born in captivity and accompanied Matata to her lessons starting when he was only 6 months old. One day, while Matata was away, Kanzi began spontaneously using the Yerkish keyboard in ways that strongly indicated he knew the meanings of the signs. He pressed the signs for “apple” and “chase”, for example, then picked up an apple and ran away with a facial expression known as a play grin. He would press keys for specific foods, and then when taken to the refrigerator would select the foods that he’d indicated on the keyboard. He used the keyboard more than 120 times on that first day alone. (Savage-Rumbaugh 1994: 135)

Prefer to watch or listen to this article instead? Here’s a video version:

The Loquacious Kanzi

After further investigation, it soon became clear that Kanzi had learned much of the symbol system, through sheer exposure rather than explicit training—remarkably parallel to how human infants learn language. Kanzi eventually mastered almost 400 signs in all. Kanzi also appears to have developed something like rudimentary word order in his symbol use. While in the first month of his use of Yerkish the order of Kanzi’s signs varied freely (using, for instance, both hide peanut and peanut hide word orders), his later utterances standardized on a verb-noun order (hide peanut), regardless of whether the noun was the agent/subject or patient/object (Progovac 2017: 57).

It later became clear to the researchers that Kanzi had not only mastered communication in Yerkish, but had acquired a rudimentary understanding of spoken English as well. Using a series of experiments carefully designed to avoid the Clever Hans effect (where the researchers’ reactions accidentally bias the subject’s behavior), researchers showed that Kanzi could understand both individual words and novel sentences he’d never encountered before. An observer in the room kept a record of what Kanzi was doing, but wore ear protectors so they didn’t know what it was Kanzi had been told to do. Kanzi was even able to correctly follow spoken instructions when they were issued entirely by telephone. He could follow complex instructions like “Fetch the carrots on the table in the kitchen and put them in the bowl in the living room.”, and ignore other carrots or other locations that were irrelevant to the task along the way. (Johansson 2019: 75–76)

In another study, the research team compared Kanzi’s English abilities with that of a 2-year-old human named Alia. Both Kanzi and Alia were given 660 spoken instructions requiring them to use objects in novel ways. Kanzi responded correctly to 74% of the instructions while Alia responded correctly to 65% (Savage-Rumbaugh et al. 1993). Savage-Rumbaugh estimates that Kanzi understood about 3,000 spoken words (Smithsonian Magazine).

Kanzi’s linguistic abilities far exceeded that of any other primates in experimental settings, despite decades of experiments. A gorilla named Koko and a chimpanzee named Washoe were taught to communicate using sign language; a chimpanzee named Lana was also taught some Yerkish, while another named Sarah used a different symbol system. In each case, it was difficult to definitively show that the primate had demonstrated anything more than a conditioned response to human-initiated cues.

Kanzi’s spontaneous symbol acquisition and subsequent robust linguistic development forced scholars to reconsider this purely behaviorist interpretation of primate communication. In his excellent book The symbolic species (Amazon | Bookshop) Terrence Deacon summarizes Kanzi’s abilities this way:

Kanzi seems to have a far better sense of what is and is not relevant to symbolic and linguistic communication. He attends to the appropriate stimulus and context parameters whereas other chimps, trained at older ages, seem to need a lot of help just recognizing what to pay attention to. Like a child attuned to the phonemes of the local language, Kanzi’s whole orientation seems to have been biased by this early experience. (Deacon 1997: 126)

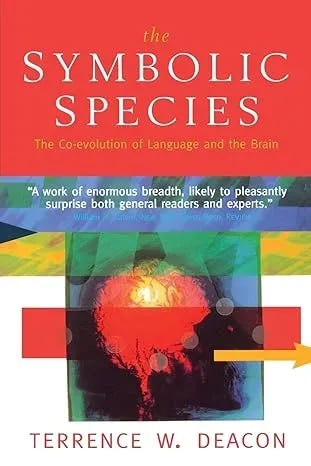

Kanzi had seemingly developed a more robust theory of mind (the ability to ascribe mental states and intentions to others) than his primate peers in other experiments. One experiment demonstrates Kanzi’s grasp of theory of mind well: Researchers would hide a grape under a cup, then ask Kanzi (or the other bonobos in the experiment), “Where’s the grape?” If the researcher was present when the grape was being hidden, the bonobo often didn’t respond to the request. But if the researcher had been absent for the grape-hiding, the bonobo would more often quickly point to the right cup. The results suggest that the bonobos had some understanding of the researcher’s state of knowledge about the location of the grape. (Townrow & Krupenye 2025)

Kanzi the Renaissance Man – er…Primate

Kanzi’s skillset didn’t stop there, however. Kanzi could gather wood, light matches, and cook omelettes and marshmallows over a fire. In one experiment designed to investigate Kanzi’s ability to create and use Stone Age tools, he was able to produce a sharp edge by flaking a stone (albeit much more crudely than early humans), then use it to cut through a rope to retrieve a food reward (Toth et al. 1993).

Kanzi was also an accomplished gamer. An old bootlegged video shows him playing Pac-Man, and more recently the popular YouTuber Christopher Slayton partnered with the Ape Initiative to test Kanzi’s abilities at learning Minecraft, the best-selling video game. Kanzi proved to be an adept miner, mastering basic Minecraft skills within minutes and going on to beat the final boss. (Slayton also helped raise over $10,000 for the Ape Initiative with his video.)

Kanzi’s skills were not without limit, however. Though his utterances did show signs of being somewhat rule-governed (as described above), they were simplistic compared to human children even early in their language learning process. Humans typically enter the two-word stage between 18 and 24 months of age, at which point basic grammatical structures like word order and semantic relationships like possession emerge. While Kanzi’s utterances relied heavily on interpretation and context, human utterances rely on linguistic rules and conventions from an early stage. For example, Kanzi used the symbol for “strawberry” as the name for the object, as a request to go where the strawberries are, as a request to eat some strawberries, and so on (Harley 2013: 65). Kanzi showed no use of function words or morphology either.

On the other hand, linguist David Gil has suggested that this free-for-all style of using words to mean different things is exactly what the first languages would have been like (Gil 2006). Before languages developed grammatical affixes, fixed word order, or function words, humans would have stitched together sentences similarly to how Kanzi did. (Gil in fact uses Kanzi’s utterances as examples in the paper; p. 97) Words were not yet strictly “verbs” or “nouns”, but instead took on their function and precise meaning from context. In fact, in his fantastic pop linguistics book The unfolding of language (Amazon | Bookshop) Guy Deutscher shows how languages proceed from having “no grammar” to having all the complex grammatical pieces we see today. All that is needed at the start is the ability to make symbolic associations between words and concepts or things—an ability that Kanzi clearly possessed.

All that notwithstanding, Kanzi’s linguistic abilities obviously can’t compare to that of even young human language learners. So does Kanzi’s behavior really count as language? If not, how should we characterize it?

Did Kanzi really have language?

Since the earliest primate language experiments, scholars have questioned both the methods and the meaningfulness of the results of these experiments, with many scholars dismissing the actions of the primates in these studies as mere behavioral conditioning. An enormous amount of criticism has been leveled at Savage-Rumbaugh in particular, most famously by Steven Pinker in his book The language instinct (Amazon | Bookshop), where he spends a page derisively dismissing all of Savage-Rumbaugh’s claims (Pinker 1994: 350).

Nativists like Steven Pinker and Noam Chomsky are quick to dismiss the putative linguistic abilities of other apes because they believe that the ability to acquire language is a genetic mutation specific to humans. In this view, any apparent linguistic abilities exhibited by other animals are the result of other, non-linguistic cognitive abilities such as conceptualization, memory, planning, etc. In a famous paper, nativist Noam Chomsky collaborated with evolutionary biologists Marc Hauser and Tecumseh Fitch to distinguish between language in a “broad sense” (all those cognitive abilities that contribute to language that I just mentioned) and language in a “narrow sense” (the abilities that are unique to humans and to language) (Hauser, Chomsky, & Fitch 2002). For nativists, then, Kanzi’s abilities are irrelevant to language and theoretically uninteresting because they merely point to other, non-linguistic abilities. For nativists, language is typically viewed as an all-or-nothing phenomenon. There is no gradual cline from non-language or proto-language to language. Instead, linguistic nativists generally adhere to a saltationist view of language evolution—a sudden mutation that occurs over one or a few generations.

Given this perspective, it’s easy to see why Savage-Rumbaugh’s work with Kanzi has garnered so much criticism. In some ways, this is science functioning exactly as it should: it is partly as a result of these criticisms that later researchers working with Kanzi have stipulated precautions in their experiments to avoid accusations of bias, anthropomorphizing, etc. And Savage-Rumbaugh herself does adopt a rather extreme view of primate linguistic abilities, which even ardent anti-nativists find hard to accept. She states, for example, that language is not confined to humans and is in fact learnable by other ape species, who are only limited by the fact that they can’t physically vocalize the sounds of human language (Savage-Rumbaugh 1994: 278). Most linguists think this claims too much. If it were true that the anatomy of the vocal tract were the only thing holding apes back from doing language, then they ought to have mastered sign language, for example. This has clearly not been the case.

In other places, however, Savage-Rumbaugh describes Kanzi’s linguistic abilities as merely being in “partial continuity” with human language (1994: 257). This is a much more reasonable position to adopt, I think. Nativists and other cynics of animal communication, because they treat language as binary, something that an individual either has or does not have, focus too much on language (ironically) and not enough on the cognitive prerequisites for language (the “broad sense” that Hauser, Chomsky, & Fitch discuss). We do in fact share many of those cognitive prerequisites with the other great apes—theory of mind, self-awareness, symbolic representations, joint attention, etc. Studies of animal communication are notable not because they demonstrate that other animals have language, but because they demonstrate that other animals possess some or all of the various cognitive abilities necessary for language, often simply to a lesser degree than humans.

At the extreme, many linguists argue that there are no cognitive abilities that are unique to language. Humans are simply the only species to have developed all of these abilities together, and to a sufficient degree. This approach to language is called functionalism or cognitive linguistics. It denies that there is any “narrow sense” of language at all. All our linguistic abilities are merely an extension or repurposing of other skills we already possess. Language is not viewed as some neatly compartmentalized ability like it is in the nativist perspective.

Functionalism allows us to posit a more gradualist (as opposed to saltationist) narrative of how we went from the non-language of animals to the language of humans. Kanzi’s linguistic abilities show us what pre-language or proto-language might have looked like among our ancestors, when we had developed some but not all of the cognitive prerequisites for language. In this perspective, contra the nativists, Kanzi has much to teach us about language.

What can we learn from Kanzi?

What made Kanzi’s language-learning journey unique compared to other primates in linguistic experiments is how young he was when he learned Yerkish and how quickly he did so—a clear parallel to how humans learn language. Kanzi’s rapid acquisition of Yerkish shows that, even though bonobos don’t engage in symbolic communication in the wild, they nonetheless have the cognitive capacity to do so (Deacon 1997: 125–127). Kanzi in fact had a handful of skills like this, each of which demonstrate that apes have latent abilities which their environmental context simply hasn’t brought forth (Johansson 2019: 77).

Likewise, humans possess a wide variety of skills that don’t occur “in our natural state” (a hunter-gatherer existence), such as solving differential equations or writing. Yet humans have always been biologically capable of such accomplishments. They merely haven’t been expressed until the modern era. (Johansson 2019: 77) In his brilliant book The dawn of language (Amazon | Bookshop), Sverker Johansson summarizes this point nicely:

From a scientific perspective these apparently unnecessary abilities can be explained instead as the expressions of a more general ability that would have been used for other purposes by our ancestors. […] The reason human beings can solve differential equations may be explained in this way—not because our ancestors had to deal with higher mathematics, but because the intellect that evolved among them in order to solve all the problems they faced can also be used for differential equations if so required. (Johansson 2019: 77–78)

In the functionalist perspective, this is precisely how language is thought to have evolved:

Cognitive linguistics considers language to be the natural consequence of applying general cognitive abilities to social interactions and our mutual desire to communicate with fellow human beings. What needs to be accounted for in this context is our general cognitive and social evolution as a whole; the origin of grammar does not require a more sophisticated explanation of its own. (Johansson 2019: 53)

So, what Kanzi’s experience teaches linguistic science is which cognitive abilities are necessary for symbolic communication, and which aren’t. Thanks to Kanzi, we can reasonably conclude that “a modern human brain is not an essential precondition for symbolic communication” (Deacon 1997: 401).

In Memoriam

Sadly, Kanzi passed away on March 18, 2025 at the age of 44. His cause of death is awaiting results from a necropsy, but Kanzi was being treated for heart disease, so that may have been a contributing factor. Kanzi was a happy, gregarious individual who loved to interact with humans, and spent his last morning being his usual joyous self, playfully chasing other bonobos and enjoying the day’s enrichment surprises.

Terrence Deacon says of Kanzi that he had “The most advanced symbolic capabilities demonstrated by any nonhuman species to date” (1997: 124), and indeed Kanzi will always be remembered for his impact on the field of linguistics, and the ways his happy antics challenged an entire theoretical paradigm in the field.

R.I.P. Kanzi. You helped us understand the nature of language better, and in doing so helped us understand ourselves a little bit more as humans as well.

📰 Press Coverage

📚 Recommended Reading

📑 Bibliography

- Ape Initiative. 2025a. Kanzi. https://www.apeinitiative.org/kanzi

- Ape Initiative. 2025b. In loving memory of Kanzi, the world’s most renowned bonobo. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1MTsAgsqofrzT6Fl2CVbBlVfhVXBz0qSg/view

- Deacon, Terrence W. 1997. The symbolic species: The co-evolution of language and the brain. W. W. Norton & Co. (Amazon | Bookshop)

- Gil, David. 2006. Early human language was isolating-monocategorial-associational. In Angela Cangelosi, Andrew D. M. Smith & Kenny Smith (eds.), The Evolution of Language, vol. 6, 91–98. Rome, Italy: World Scientific. https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812774262_0012.

- Greenfield, Patricia Marks & E. Sue Savage-Rumbaugh. 1990. Grammatical combination in Pan paniscus: Processes of learning and invention in the evolution and development of language. In Sue Taylor Parker & Kathleen Rita Gibson (eds.), “Language” and intelligence in monkeys and apes (Comparative Developmental Perspectives), 540–578. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511665486.022.

- Harley, Trevor A. 2013. The psychology of language: from data to theory. 4th edn. Psychology Press. (Amazon | Bookshop)

- Hauser, Marc D., Noam Chomsky & W. Tecumseh Fitch. 2002. The faculty of language: What is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? Science 298(5598). 1569–1579. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.298.5598.1569.

- Johansson, Sverker. 2021. The dawn of language: How we came to talk. (Trans.) Frank Perry. MacLehose Press. (Amazon | Bookshop)

- Progovac, Ljiljana. 2015. Where is continuity likely to be found? In Robert Seyfarth, Dorothy Cheney & Michael Platt (eds.), The social origins of language (Duke Institute for Brain Sciences Series 1), 46–61. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400888146-005.

- Savage-Rumbaugh, Sue & Roger Lewin. 1994. Kanzi: The ape at the brink of the human mind. John Wiley & Sons. (Amazon | Bookshop)

- Savage-Rumbaugh, Sue & Duane Rumbaugh. 1993. The emergence of language. In Kathleen R. Gibson & Tim Ingold (eds.), Tools, language & cognition in human evolution, 86–108. Cambridge University Press.

- Savage-Rumbaugh, Sue, Kelly McDonald, Rose A. Sevcik, William D. Hopkins & Elizabeth Rubert. 1986. Spontaneous symbol acquisition and communicative use by pygmy chimpanzees (Pan paniscus). Journal of Experimental Psychology 115(3). 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.115.3.211.

- Savage-Rumbaugh, E. Sue, Jeannine Murphy, Rose A. Sevcik, Karen E. Brakke, Shelly L. Williams, Duane M. Rumbaugh & Elizabeth Bates. 1993. Language comprehension in ape and child. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development 58(3/4). https://doi.org/10.2307/1166068.

- Toth, Nicholas, Kathy D. Schick, E.Sue Savage-Rumbaugh, Rose A. Sevcik & Duane M. Rumbaugh. 1993. Pan the tool-maker: investigations into the stone tool-making and tool-using capabilities of a bonobo (pan paniscus). Journal of Archaeological Science 20(1). 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.1993.1006.

- Townrow, Luke A. & Christopher Krupenye. 2025. Bonobos point more for ignorant than knowledgeable social partners. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 122(6). e2412450122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2412450122.

If you'd like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.