Curiouser and curiouser… A (short) journey through words and language

Join League of the Lexicon game creator Joshua Blackburn as he follows the threads of his curiosity about keyboards

Before I wrote The Language-Lover’s Lexipedia, and before I created my game League of the Lexicon—a quiz game about words and language—I ran a communications agency. For over a decade I told clients that it wasn’t what I knew about their business that mattered, but my curiosity about what I didn’t know. It might sound like an ingenious excuse for being ill-informed, but what I meant was that because I didn’t know what they knew, I asked questions; and because I asked questions, I saw their world differently.

I mention this because that’s how I think about words and language too. I’m neither a linguist nor a lexicographer—I didn’t even take English at university; but loving language doesn’t need an English degree, only curiosity. And it is this curiosity that has led me deep into the rabbit holes of language.

It often begins with a question—something that occurs to me mid-conversation or while staring at an ad on the London Underground. Questions like:

- Where does punctuation come from?

- How do Chinese keyboards work?

- How can I get a word in the dictionary?

- Why are pedants pedantic?

- Why are words with a K funny? (And why are words with a T not?)

- How are IKEA products named?

And on it goes.

For me, language is a loose thread that I can’t resist pulling on; and when I start, it’s hard to stop, because the thread is infinite. So I’m going to try an experiment for this article about linguistic curiosity; I’m going to write about the first thing my eyes land on, then keep pulling the thread to see where it leads…

keyboard (n.)

The first key-boards [sic] were found on musical instruments, specifically organs, pianos, harpsicords and the like, with the word first appearing in the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) in 1776. The first citation for a type-based keyboard is 1846, in relation to a telegraphy machine. Given the early design of these devices, it was an obvious choice, since they used actual piano keys, transposed from hammering strings to inputting letters.

Speaking of ancient keyboards…

…it seems strange to see the ampersand—the squiggly symbol that means and—featured on such an old keyboard; after all, it doesn’t get much use these days. But the truth is, the fortunes of this elegant glyph have plummeted over the last century.

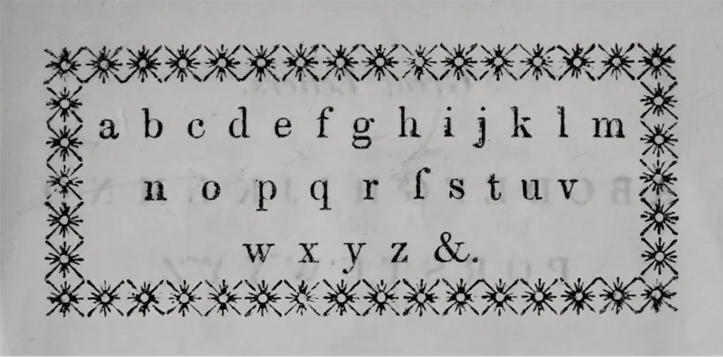

Up to the 20th century, the ampersand was often taught as the 27th letter of the alphabet; today, it is relegated to corporate logos and space-squeezed signs. Indeed, as grammarian June Casagrande wrote in 2019: “Here’s a simple guideline for using ampersands: Don’t.” How the mighty have fallen.

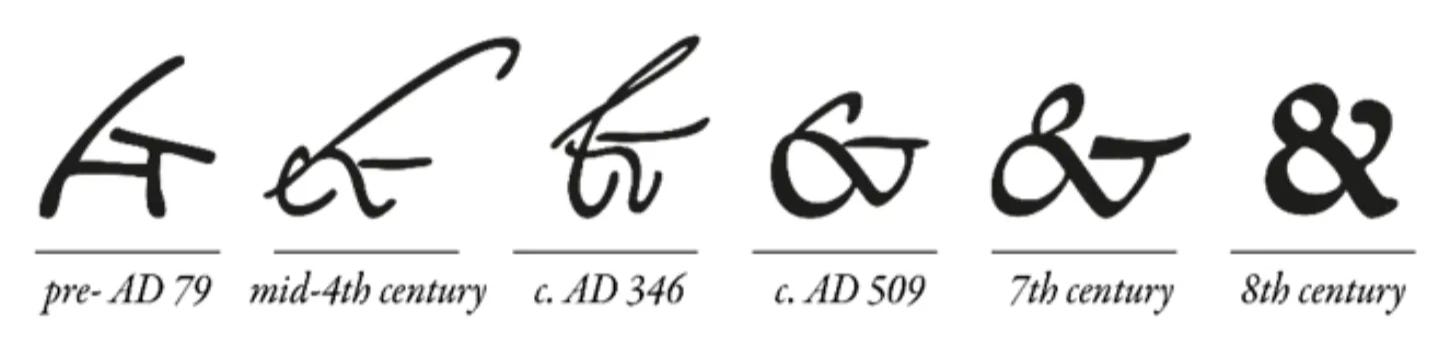

The earliest ampersand was found on a wall in Pompeii (see below) where it was a ligature combining e and t of the Latin et, meaning ‘and’. Its name is a contraction of and per se and, a Latin-English hybrid that essentially means: ‘this symbol means “and”’. Children chanting their ABCs would conclude with: “X, Y, Z, and per se and”; spoken quickly, those last syllables combined to create its name, ampersand. When people wrote by hand—or carved on stone—the ampersand was no doubt useful; but modern keyboards have made its time-saving qualities redundant.

Incidentally, the ampersand wasn’t the first symbol to represent ‘and’. A century and a half before the destruction of Pompeii, Tiro, secretary and slave of the Roman statesman Cicero, invented the Tironian et, that looked like this: ⟨⁊⟩. It was used in the Gothic script known as blackletter, but is now only found in Irish Gaelic.

Speaking of Cicero…

…you may be more familiar with his work than you realise.

When graphic designers lay out work, they use placeholder text, and for as long as most people can remember, it’s been a chunk of Latin-sounding words starting “Lorem ipsum…” But where this text came from, and when it was first used, was a mystery for a long time.

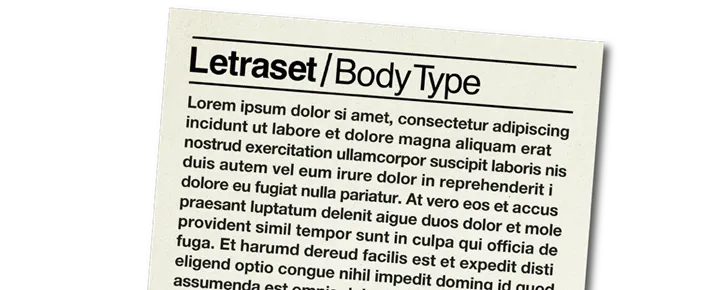

It’s often said that the practice started among 16th-century printers, but this is untrue. The first evidence of Lorum ipsum is the 1960s, where it appeared in adhesive transfer sheets made by Letraset which were used for text layout. It then secured its place among graphic designers when it was adopted in 1985 by Aldus PageMaker, the desktop publishing software for Apple computers.

The text itself was assumed to be gibberish, until classicist Richard McClintock showed that it came from mangled fragments of Cicero’s De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum (‘About the Ends of Good and Evil’), written around 45 BC. It has thus become one of the most accidentally (mis-)quoted Latin texts in history.

Speaking of misquotations…

…did Groucho Marx really say, “I didn’t say that, and even if I did, I didn’t mean it”? Sadly not. Despite being widely shared online, it is, appropriately, a misquotation. Or rather, a misattribution. Likewise Yogi Berra’s “I never said half the things I said”, which he famously didn’t say, but people like to say he did.

Misquotations are nothing new, but thanks to social media and hallucinatory AI, they’re booming. There are three types of misquotation: the thing that was almost said, the thing that was never said and the thing that may have been said, but not by the person said to have said it. The problem is that determining the truth can be complicated, but sharing a misquotation is easy. Or as quotation compiler Robert Andrews is said to have said—but, again, didn’t—“Most quotations end up being misquotations.”

People love reading clever things said by famous people—Oscar Wilde, Coco Chanel, Mark Twain, Albert Einstein and the like. As a result, well-known figures are commonly attached to nuggets of wisdom they never uttered. But correcting these errors is difficult when people don’t want them corrected. “If you’re going through Hell, keep going” wasn’t Winston Churchill, but it’s what people want him to have said. Just as they want to believe Marilyn Monroe delivered the sassy line, “Well-behaved women seldom make history.” It’s a lot less exciting that the real author was Harvard professor, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich.

Mark Twain probably didn’t say “Never let the facts get in the way of a good story” either, making it an apt motto for those who share dubious quotations. However, if you belong to the minority of people who care about the accuracy of quotations, visit the Quote Investigator, who provides both facts and good stories.

Speaking of mistakes…

…errors in books are called corrigenda or errata. For a long time, such mistakes were common in printing. Shakespeare’s First Folio is full of them, and many first editions—from writers like Niccolò Machiavelli, Jane Austen, Oscar Wilde, Charles Dickens and more—feature errata slips. Even the Declaration of Independence has errata, with an erratum in the errata itself.

Today, however, mistakes can be embarrassing and costly. It certainly was for Penguin Australia who had to destroy 7,000 copies of The Pasta Bible in 2010 because the recipe for tagliatelle with sardines and prosciutto listed “freshly ground black people” in the ingredients.

Fortunately not all mistakes require a work to be pulped, often an errata slip will do—but these can be awkward too. When Faber and Faber published Moortown by Ted Hughes in 1979, there was a typo in “Night Arrival of Sea Trout”, that required the correction, “for ‘rape’, read ‘nape’.” But at least there was good news when the publisher of the Australian Dictionary of National Biography corrected one entry with the information: “For ‘died in infancy’ read ‘lived to a ripe old age at Orange’.”

Some mistakes are so bad they’re good. Susan Anderson says she’s still haunted by the typo on page 293 of her sizzling romance novel, Baby, I’m Yours: “He stiffened for a moment but then she felt his muscles loosen as he shitted on the ground.” And scientists at the Large Hadron Collider in Cern have stopped counting the number of references to their work at the “Large Hardon Collider”.

But not all mistakes are costly. One of the most valuable Harry Potter books sold in auction was a first edition hardback, where the title on the back cover is misspelled “Harry Potter and the Philospher’s Stone”. It’s not even the only mistake in the book. But thanks to these typos, it sold for £68,812 in 2019.

Speaking of typos…

…brings us back to keyboards and the origin of the QWERTY layout, a subject that has been much debated.

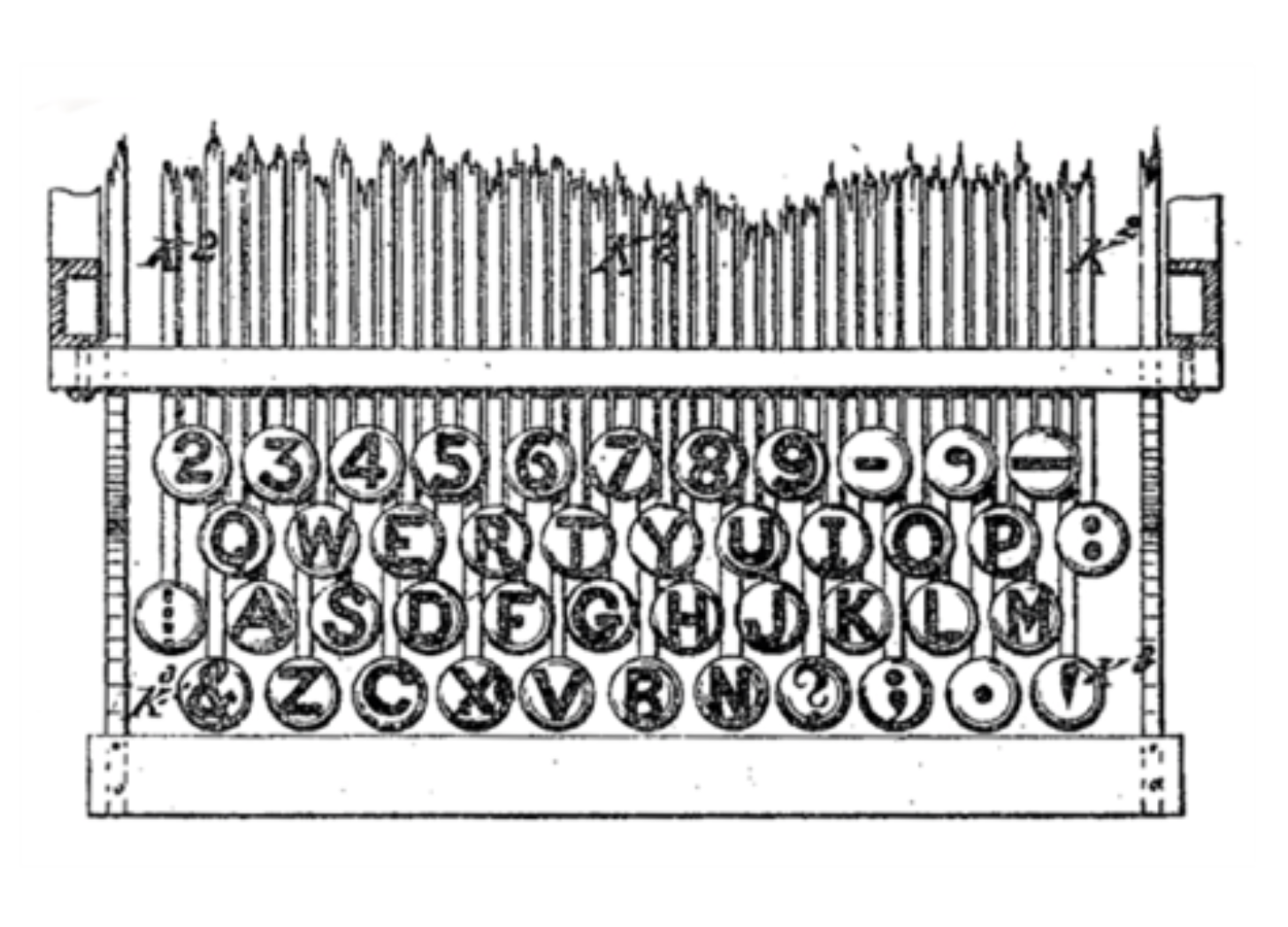

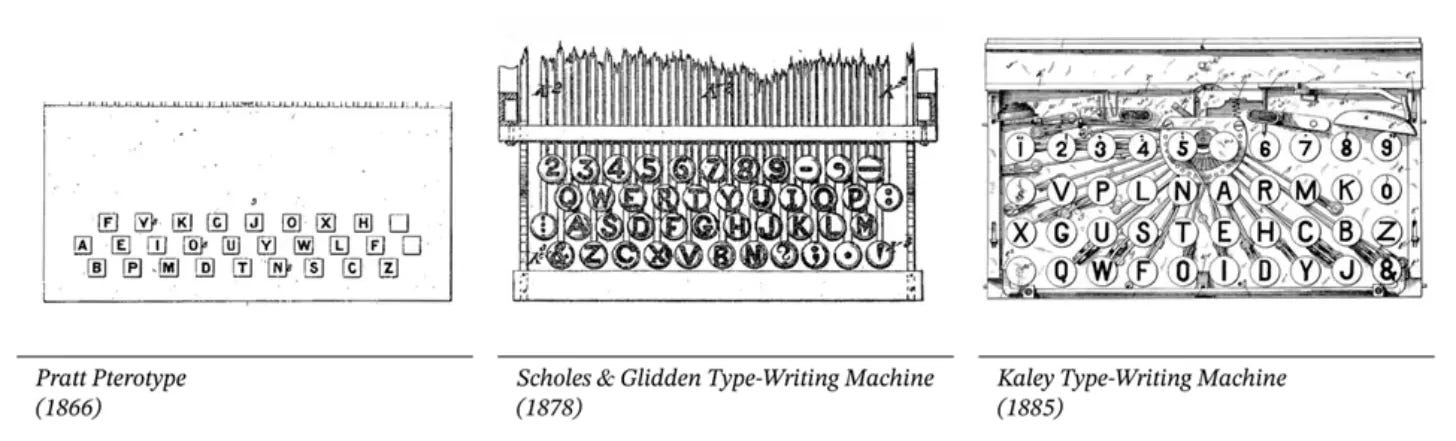

What’s known is that the QWERTY arrangement was created by Christopher Latham Sholes for the “Sholes and Glidden type-writer” [sic], which became the Remington No. 1, the first commercially viable typewriter.

It’s commonly said that Sholes’ layout, first documented in an 1878 patent, was designed to avoid the mechanical problem of type bars clashing within the machine. Far from being the best layout for speed, the story goes, QWERTY was designed to slow typists down so they wouldn’t jam the type basket. It’s also been claimed that the QWERTY layout was chosen so that salesmen could type TYPEWRITER with one finger from the first line of letters. It’s true that you can, but I wouldn’t read anything into it.

Since many of the early users of typewriters were morse code operators, for whom speed was a priority, it is highly improbable that Sholes would design a keyboard to deliberately inhibit speed. In the early days of the typewriter, inventors explored different layouts (see below), but all with the aim of improving typing speed. As John Harrison wrote in his 1888 Manual of the Type-Writer:

Why its alphabet should begin with Q, and end with M, is mysterious at first sight. But the reason of this disorder soon becomes clear. The keys are arranged so that greater facility is given to fingering letters than if the letters were placed in their usual order.

The question is not so much how QWERTY came to be devised as how it came to dominate, and the answer to this lies in Remington’s position as the leading manufacturer of typewriters. As their typing schools and teaching methods promoted QWERTY, other manufacturers fell into line and it became the de facto standard. QWERTY almost certainly isn’t the best keyboard layout—even Sholes proposed a new design before his death—but the combination of technology lock-in, the network effect and the efforts of the leading manufacturers cemented its position.

And thus we come full circle, almost as if I engineered it that way. But I had to. I could have gone from mistakes to malapropisms to humour to sound symbolism to language learning and beyond. Because the world of words never ends. And for those with a curious mind, that is the joy of it.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.