Why is the ⟨g⟩ in “longevity” pronounced twice?

How the spelling of “longevity” is playing a mental trick on you

Why is the ⟨g⟩ in longevity pronounced twice?

To some of you, this may seem like an odd question. If so, that’s probably because you don’t pronounce the ⟨g⟩ in longevity twice.

You see, there are two common pronunciations of longevity: one where the first syllable sounds like lawn, and one where that syllable sounds like long. In the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), for a General American dialect, those two pronunciations might be transcribed like this:

- When the first syllable sounds like lawn, ⟨g⟩ is pronounced once: /lɑnˈd͡ʒɛv.ɪ.ti/

- When the first syllable sounds like long, ⟨g⟩ is pronounced twice: /lɑŋˈd͡ʒɛv.ɪ.ti/

There is of course a lot of additional variation in how this word is pronounced across various dialects, but the relevant difference here is whether the nasal consonant before the ⟨g⟩ is pronounced as /n/ (like at the end of the word sin) or /ŋ/ (like at the end of the word sing). That /ŋ/ sound is called eng (or engma) in linguistics. From what I can tell, the use of eng in longevity is more common in North American English, Australian English, and New Zealand English than it is in British English, but both pronunciations can be heard anywhere in the core Anglosphere.

The eng pronunciation also seems to be a more recent development, based solely on the fact that major dictionaries (the OED, Merriam-Webster, Dictionary.com) don’t even list that pronunciation yet. Wiktionary, however, does list this variant (which is an excellent example of how good Wiktionary’s descriptive coverage has become, thanks to crowdsourcing its data).

Among those who do pronounce longevity with an eng, however, the mystery of why the ⟨g⟩ gets pronounced twice is deeply puzzling, at least if the number and view count of online videos about this question are any indication:

@iambrianfink How do YOU pronounce it? 😤 #english #weirdwords #longevity #brianfink #fyp

♬ original sound - Brian Fink

It even caught the attention of some popular online educators!

@jasonkpargin ♬ Elevator Music - Bohoman

Of course, videos like these tend to spark backlash in the comments from people who either insist that there’s only one correct pronunciation of a controversial word, or claim to have never heard the alternate pronunciation.

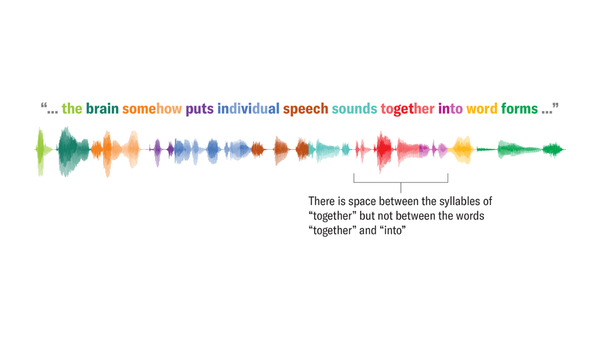

I say “claim” because few people are actually so linguistically isolated that they’ve genuinely never heard common alternate pronunciations of everyday words. If they’re globally connected enough to be commenting on language videos on the internet, they’ve likely encountered those other pronunciations but simply weren’t paying attention. This isn’t a criticism of how observant people are. Your brain ignores a great deal of the linguistic variation it encounters because it’s focused not just on the sounds you hear but on identifying the words being used and the message being conveyed. Our brains are incredible categorization machines, capable of disregarding incidental differences between stimuli in order to identify instances of the same abstract type. Even widely variant pronunciations of a word still get categorized as instances of the “same” word by your brain. We would not be able to do language with each other if our brains weren’t capable of ignoring these interpersonal disparities.

Ironically, it’s precisely our incredible linguistic abilities and our brains’ ability to filter out semantically irrelevant differences which make people so upset when those differences are pointed out to them. It makes for some great internet ragebait, as the above videos show.

“I’ve never heard anybody say it that way.” ~ somebody on the internet who has in fact heard many people say it that way many many times because it’s a common pronunciation but they just weren’t paying attention, probably

Anyway, I digress. Now that we’ve established that both /lɑnˈd͡ʒɛv.ɪ.ti/ and /lɑŋˈd͡ʒɛv.ɪ.ti/ are in fact common pronunciations of longevity, let’s talk about how it got to be pronounced that way, and how its spelling is actually playing a neat mental trick on you.

The spelling of longevity is messing with your head

You might be tempted at first to explain the eng pronunciation by saying that the ⟨g⟩ is shared by two different syllables—it’s part of both the first syllable, long-, and the second syllable, -gev-. And you’d be clever for suggesting this, because this is in fact something that happens occasionally in English. Linguists often analyze words like dinner and donor as containing an ambisyllabic consonant—a consonant sound that is part of two syllables at once. (Note that we’re talking about sounds here, not letters.) However, the ⟨g⟩ in longevity isn’t one of those cases. The syllable boundary around that ⟨g⟩ is actually quite clear: the first syllable is /lɑŋ/ or /lɑn/ depending on your pronunciation, and the second syllable is /d͡ʒɛv/.

What are the syllables in donor, hurry, and lemon? Does thinking about that make your head hurt? If so, you’re not alone! Linguists puzzle over this same problem. If you’re a paid subscriber, stick around til the end of this article for some bonus content about ambisyllabic consonants and how linguists think about syllable boundaries.

In order to understand what’s happening with longevity, you need to make a mental distinction between how the word is spelled and how it’s pronounced:

- spelling: ⟨longevity⟩

- pronunciation: /lɑŋˈd͡ʒɛv.ɪ.ti/ (eng pronunciation)

You’ll notice that the spelled version of longevity has ⟨angle brackets⟩ around it, while the pronunciation version has /slashes/ around it. Linguists use these conventions to clarify when we are talking about the written representation of a word (its spelling) versus when we are talking about the spoken representation of a word (its pronunciation).

If you pay attention to the pronunciation of longevity rather than its spelling, you might notice something odd given the subject of this article: there’s no /g/! Even though longevity is spelled with one ⟨g⟩ letter, it doesn’t have a /g/ sound when you write it phonetically. That’s because in the International Phonetic Alphabet, the symbol /g/ always refers to the “hard” /g/ as in go or good. Since longevity doesn’t have a “hard” /g/ in the pronunciation, there’s no /g/ in its phonetic transcription.

In English spelling conventions—English’s orthography, if you prefer the technical term—the letter ⟨g⟩ is commonly used to write a few different sounds:

| Name | IPA Symbol | Example Words |

|---|---|---|

| hard G | /g/ | go, garden, gum |

| soft G | /d͡ʒ/ | giant, gentle, gym |

| fricative G | /ʒ/ | beige, mirage, rouge |

| silent G | — | gnat, sign, foreign |

And certain combinations of letters (known as digraphs) with ⟨g⟩ also commonly represent certain sounds:

| Digraph | Pronunciation | Example Words |

|---|---|---|

| ⟨ng⟩ | /ŋ/ | sing, ring, bang |

| ⟨gh⟩ | /g/ | ghost, ghetto, Afghanistan |

| ⟨gh⟩ | /f/ | laugh, cough, enough |

| ⟨gh⟩ | — | high, though, sigh |

In the word longevity, the letter ⟨g⟩ is being used to represent two of these “g sounds” at once: the eng sound /ŋ/ and the “soft g” sound /d͡ʒ/. Even though neither of these is technically a /g/ sound in the sense of being a “hard g”, that’s why you perceive there to be two ⟨g⟩’s in the word—it contains two different sounds commonly associated with the letter ⟨g⟩ in English.

You may have also just noticed that the word English itself has this same quirk: the ⟨g⟩ represents both /ŋ/ and /g/ at the same time (though the story behind why that happens in the word English is actually different from why it happens in longevity, even though the result is similar).

How did this dual use of ⟨g⟩ come about? Which sound did that ⟨g⟩ originally represent? Why isn’t it spelled ⟨longgevity⟩ instead? To understand how we got here, we need to trace longevity's journey from Classical Latin to modern English.

The history of longevity

Even as Latin broke up into the distinct Romance languages we have today, people still thought they were speaking Latin, and so they would have read Latin texts with their own vernacular pronunciations.

The word longevity was first documented in English in 1569, making it one of the many words borrowed from Latin during the Renaissance. The Latin word it came from was longaevitās ‘long life’, which itself is a combination of longus ‘long’ + aevum ‘time, eternity; age, generation’ + -tās, an abstract noun suffix indicating states of being.

It’s important to note that not all sounds are meaningful in all languages. For example, Latin didn’t make a meaningful contrast between /n/ and /ŋ/ like English does. You can find pairs of words in English like sin /sɪn/ vs. sing /sɪŋ/ which prove that /n/ and /ŋ/ are meaningfully distinct sounds in the language, but you can’t find such pairs in Latin. Pairs of words like this which differ by only a single sound are called minimal pairs, and they are how linguists determine which sounds are distinct and meaningful in a language. In English, you have to be able to recognize the difference between /n/ and /ŋ/ if you want to be able to distinguish sin from sing or kin from king. This is what I mean what I say that there’s a “meaningful contrast” between /n/ and /ŋ/ in English. When a language does make a meaningful contrast between two sounds like this, we call them distinct phonemes.

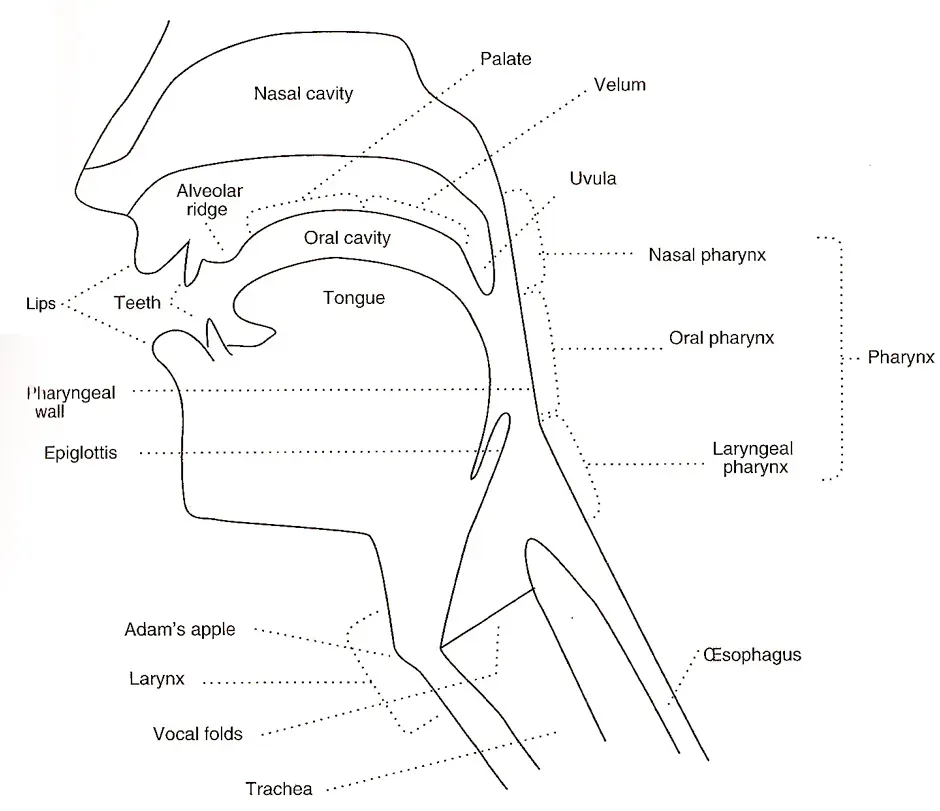

Latin had a phoneme /n/, written as ⟨N⟩, but not a phoneme /ŋ/. Instead, /n/ could be pronounced as either [n] or [ŋ] depending on the sounds around it. So while Latin speakers pronounced an eng [ŋ] in many words, they didn’t perceive it as a distinct sound; they perceived it as just a variation of /n/. In particular, the [ŋ] variant was only used before other velar consonants like /g, k/. (When a phoneme’s pronunciation changes to be more like the sounds around it in this way, the process is called assimilation.)

In technical terms, we’d say that the [ŋ] pronunciation is an allophone of the phoneme /n/. An allophone is simply a pronunciation variant of a particular phoneme, usually conditioned by the sounds around it. In English, for instance, the phoneme /t/ can be pronounced [t] (plain), [tʰ] (aspirated), [ʔ] (glottalized), [t̚] (unreleased), and [ɾ] (flapped). Each of these pronunciations is a different allophone of /t/, and each has its own rules about when it’s used. The aspirated [tʰ], for example, is generally the pronunciation used at the beginnings of syllables. But if you’re a native English speaker, you just hear all these different sounds as /t/. [t, tʰ, ʔ, t̚, ɾ] are not meaningfully distinct in English, just like [n] and [ŋ] were not meaningfully distinct sounds in Latin.

Notice the additional transcription convention I’ve introduced here too: when a sound is a distinct phoneme in a language, we write it between /slashes/; but when a sound isn’t a meaningfully distinct phoneme, we write it between [square brackets]. The first is a phonemic transcription and the second is a phonetic transcription.

Putting all this together, it means that longaevitās in Classical Latin would have been pronounced as [laŋˈɡaᵉ.wɪ.taːs] but perceived as /lanˈɡaᵉ.wɪ.taːs/, with /n/ pronounced as [ŋ] due to assimilation with the following /g/.

Confusingly but unsurprisingly, however, Latin pronunciation changed over the centuries. Even as Latin broke up into distinct languages like French, Italian, Portuguese, Romanian, Spanish and numerous others (what we today call Romance languages, or descendants of Latin), people still thought they were speaking Latin, and so they would read Latin texts with vernacular pronunciations. For example, the Latin word saeculum ‘generation’ was pronounced /ˈsaᵉ.ku.lum/ in Classical Latin, but in ninth-century Spain it was read as /sjeglo/ (Modern Spanish siglo ‘century’). To us, that might not seem like a very logical way to pronounce ⟨saeculum⟩, but the same kind of “illogical” transformation also happened in English: think about how English speakers today say knight as /naᶦt/ today rather than the original pronunciation /knɪxt/ (Wikipedia: Ecclesiastical Latin).

It took scholars centuries to recognize the Romance descendants of Latin as distinct languages. The first grammar of a Romance language wasn’t even published until 1492! It came in the form of Antonio de Nebrija’s grammar of Castilian Spanish (although we see hints of early Spanish as far back as the 900s in the Glosas Emilianenses, and early French in the Oaths of Strasbourg in 842).

As a result of the sound changes throughout Europe and in Italy specifically, the pronunciations used by the Catholic Church for Latin wound up being quite different from the original pronunciations of Classical Latin. Today we call this Ecclesiastical Latin, the variety of Latin used in Christian literature throughout the Middle Ages and in the Catholic Church today.

The genesis of Ecclesiastical Latin had an odd result for our history of longevity: because English scholars during the Renaissance only knew Ecclesiastical Latin pronunciation and not Classical pronunciation (linguists didn’t fully piece together how Classical Latin sounded until the florescence of historical linguistics in the 1800s), whenever they borrowed words from Latin, they did so with their Ecclesiastical pronunciations. This meant that when longevity first entered English in 1569, it was probably pronounced something like /lɑnˈd͡ʒɛ.vi.tas/ instead of the Classical [laŋˈɡaᵉ.wɪ.taːs]. The ⟨g⟩ was now pronounced as a “soft g” /d͡ʒ/, and the /n/ pronounced as [n] rather than the traditional eng [ŋ]. So when the word longevity first entered English, the ⟨g⟩ only represented the “soft g” sound /d͡ʒ/—it wasn’t yet doing double duty as it does for many speakers today. The eng pronunciation actually had to be reintroduced later, ironically making the pronunciation more like the original Classical Latin pronunciation.

What caused the eng pronunciation to come full circle like this? Well we know it’s not due to assimilation like it was in Latin. In Classical Latin, the /n/ in longevity was pronounced as [ŋ] because that made the sound more similar to the /g/ which followed it—both [ŋ] and [g] are pronounced with the tongue touching the velum (soft palate) at the back of the roof of the mouth. But this can’t have happened in English because the sound following the /n/ is /d͡ʒ/ rather than /g/, and /d͡ʒ/ is pronounced at the front of the mouth at the alveolar ridge. So pronouncing longevity with an eng [ŋ] arguably makes the word harder to pronounce because the tongue has to move rapidly between more distant articulatory targets.

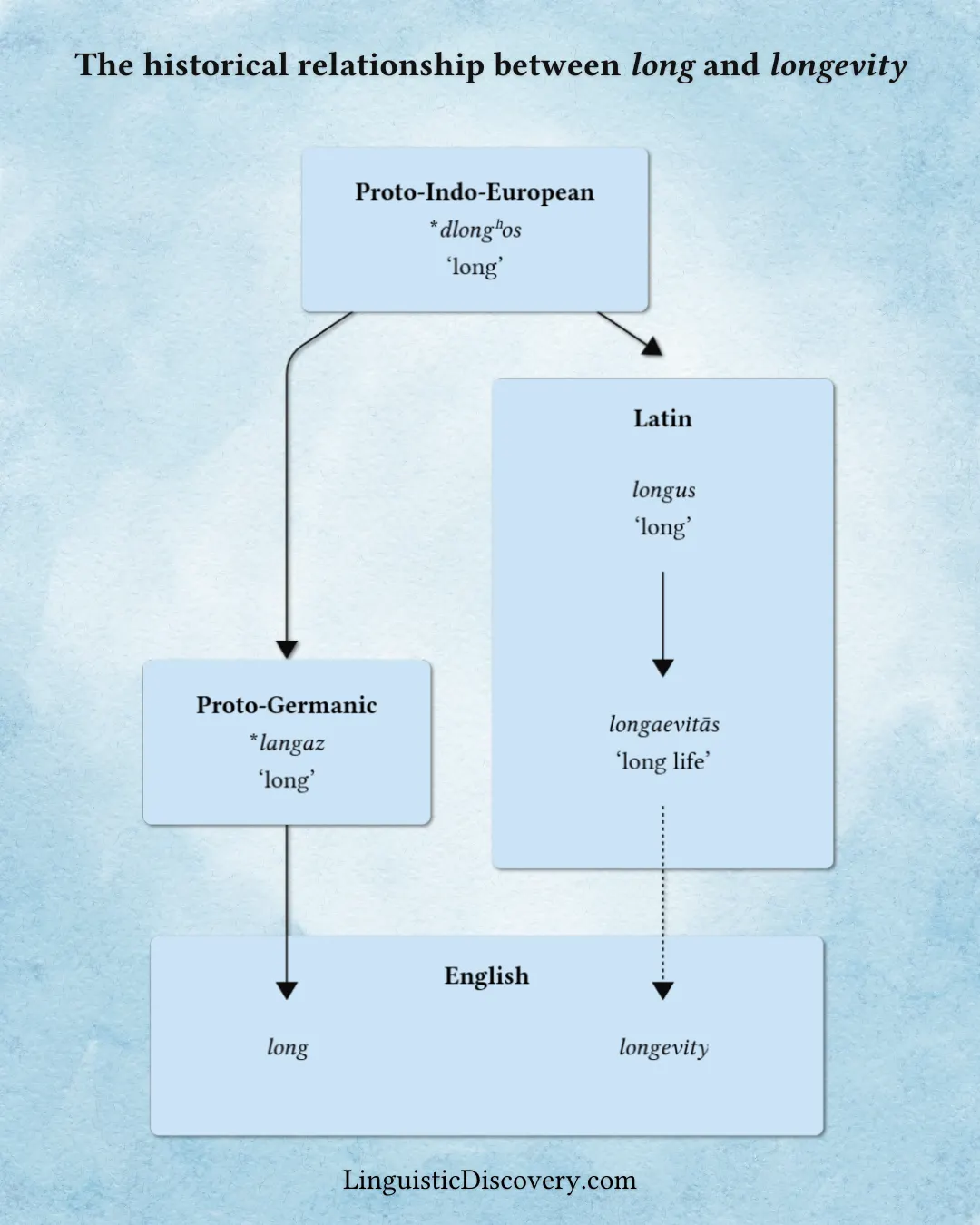

Instead, it seems that the main reason for the shift in the pronunciation of longevity is because speakers made an analogy to the word long in English, which of course is pronounced with an eng, as /lɑŋ/. And this is a very reasonable thing to do! The word long is, after all, historically related to longus, which was part of that Classical Latin word longaevitās. The English word long wasn’t borrowed from Latin longus, though; instead they developed independently, in parallel, from the original Proto-Indo-European root *dlongʰos ‘long’. And even if you didn’t know that longevity actually comes from Latin, it’s entirely reasonable to make an association between long and longevity since the latter literally means ‘a long duration of individual life’. English speakers may not know the exact details of how long and longevity are related, but it seems to them that there must be some connection between them.

This makes the word longevity a subtle case of folk etymology—reinterpreting a word or phrase as having different elements than it originally did because the original elements are unfamiliar to the speaker. In this case, few English speakers know that longevity is actually from a Latin word longaevitās, so they reanalyze it as being from the English word long instead, and assume the -ev- part just has some other meaning they’re not aware of, maybe connected to words like brevity and levity. Of course, there is no actual connection between brevity/levity and -ev- or the original Latin aevum, but the mere existence of other words ending in -evity this makes it easier for speakers to analogically reinterpret longevity this way.

This is why I actually like calling folk etymology analogical reanalysis or etymological reinterpretation instead (Cienkowski 2008). The word folk has subtle pejorative implications of ignorance, when what’s actually happening here is some clever analogical reasoning on the part of speakers. And what’s pretty incredible about this is that almost no one is sitting around consciously thinking about longevity this way before they say it with an /ŋ/. All this analogizing is happening subliminally and automatically. Humans are incredible pattern-recognition machines, especially when it comes to language.

And so we now have the complete answer to our orthographic mystery: the ⟨g⟩ in longevity is pronounced twice because it was borrowed from Latin at a point when the pronunciation of Latin had undergone significant changes, and then it was reinterpreted as being based on the English word long rather than the original Latin word longaevitās. Along the way, we learned a little about how our brains process language, how spelling relates to pronunciation, and how language might change over time. So next time you notice someone pronounce longevity—or any word!—differently from how you do, it’s worth pausing to appreciate the amazing confluence of cognitive, historical, physiological, and analogical factors that brought those differences about, and yet still make us capable of understanding each other.

🙏 Credits

This issue of the Linguistic Discovery newsletter was edited by Amy Treber. If you’re looking for professional copyediting services, email Amy at amytreberedits@gmail.com.

The final responsibility for any mistakes or omissions is of course still wholly my own.

📑 References

- Cienkowski, Witold. 2008. The initial stimuli in the processes of etymological reinterpretation (so‐called folk etymology). Scando-Slavica 15(1). 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00806766908600524.

- Gordon, Matthew K. 2016. Phonological typology (Oxford Surveys in Phonology & Phonetics 1). Oxford University Press.

- Jensen, John T. 2000. Against ambisyllabicity. Phonology 17(2). 187–235. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952675700003912.

- Treiman, Rebecca & Catalina Danis. 1988. Syllabification of intervocalic consonants. Journal of Memory and Language 27(1). 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-596X(88)90050-2.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.

🌟 Bonus Content: How do we know where syllable boundaries are?

Our judgements about syllable boundaries are inconsistent and unreliable, which is probably a reflection of the fact that syllables themselves are, like almost everything in language, fuzzy categories centered around a clear prototype.

As mentioned above, linguists often analyze some words in English as containing an ambisyllabic consonant—one which is part of two syllables at once. Note that we’re talking about sounds here, not letters. Frequently in English a single sound will be written using more than one letter, and that’s what’s happening in the words below. How would you divide these words into syllables? Is the middle consonant sound part of the preceding syllable, the following syllable, or both?

- better

- butter

- dinner

- donor

- funny

- habit

- hammer

- happy

- hobby

- hurry

- lemon

- running

If trying to figure out the syllable boundaries in these words makes your head hurt, you’re not alone: “Determining the exact nature of syllables and their boundaries has proved notoriously difficult” (Jensen 2000: 187). Linguists debate whether these cases should even be analyzed this way (Jensen 2000), and speakers often disagree on exactly where syllable boundaries lie (Gordon 2016: 83). In experiments, speakers do have strong intuitions that words like happy, hammer, and hobby have an ambisyllabic consonant (Rubach 1996), but they seem to be influenced by the fact that these words also happen to be spelled with two consonants (Treiman & Danis 1988). Speakers are less likely to consider the /n/ in pony to be ambisyllabic than they are the /n/ in punny, even though pony and punny have the same syllable structure (pony /poᶷni/ vs. punny /pʌni/). Liquid consonants /l, r/ and nasal consonants /m, n, ŋ/ were also judged to be ambisyllabic more often than other consonants (Treiman & Danis 1988).

So our judgements about syllable boundaries are inconsistent and unreliable, which is probably a reflection of the fact that syllables themselves are tricky to define and not nearly as cleanly delineated in language as you were taught in school. They are, like almost everything in language, fuzzy categories centered around a clear prototype.

Thankfully, this fuzziness isn’t actually a problem for our understanding of longevity, because the ⟨g⟩ in longevity isn’t ambisyllabic anyway, as explained in the article. Linguists may not know what syllables are, but we can still identify the clear cases, and this is one of them.

However, there is disagreement amongst dictionaries about whether the /v/ in longevity belongs to the second syllable or the third. (For the purpose of this article I assumed it belongs to the second.) What’s neat about this disparity is that it shows how syllable boundaries can sometimes be sensitive to morpheme boundaries: /v/ is syllabified as part of the syllable /d͡ʒɛv/ because that’s where the stem ends and the suffix -ity begins. If not for that suffix, the /v/ would be the start of the following syllable instead, which is more typical for English.