From counting to cuneiform: How writing was invented

The earliest version of cuneiform wasn't used to write language at all—it was used to count! And that Sumerian system of counting still influences our counting systems today. Here's the story of Sumerian numerals.

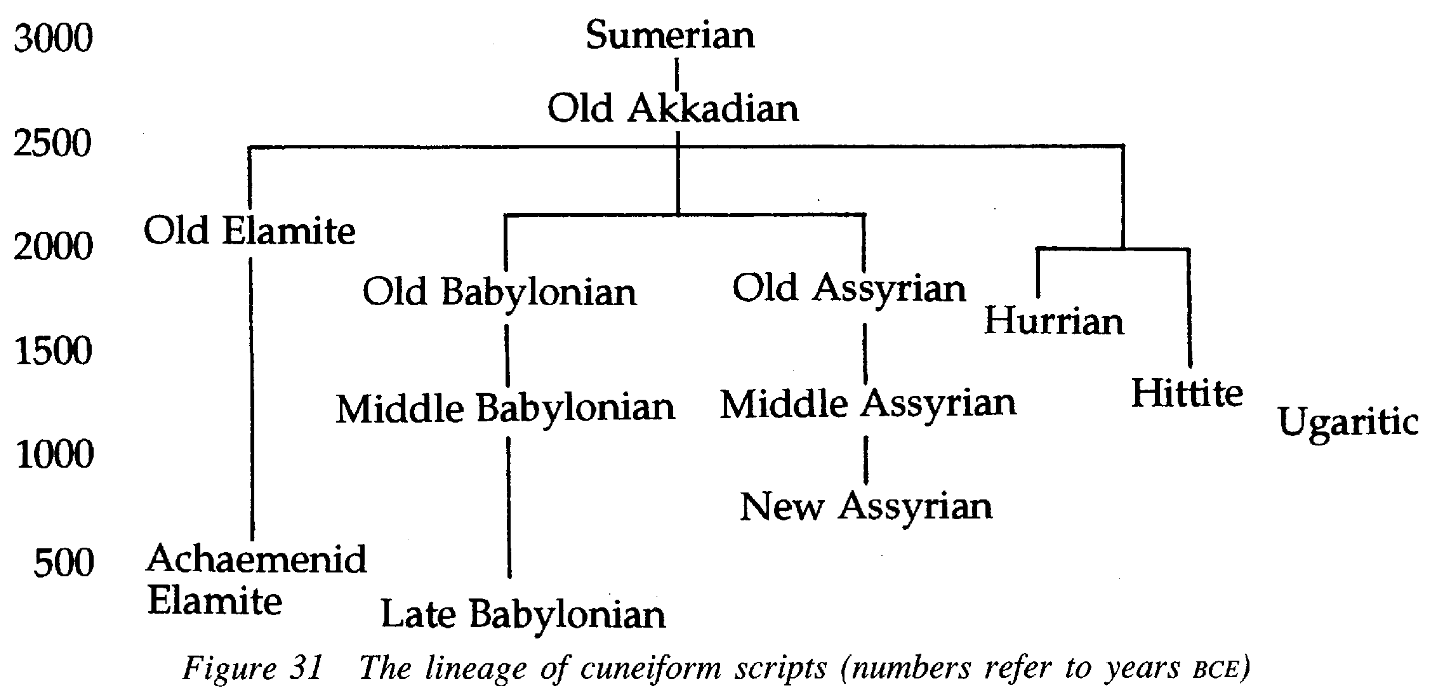

The earliest known writing system, cuneiform, was first used to write the Sumerian language (c. 3300 BCE), and later the Akkadian, Babylonian, Assyrian, Elamite, Hurrian, Hittite, Old Persian, and Ugaritic languages (Figure 1).

But the earliest version of cuneiform wasn’t used to write language at all—it was used to count! And that Sumerian system of counting still influences our counting systems today.

This is the story of Sumerian numerals.

Prefer to watch or listen to this article instead? Here's a video version:

Proto-Cuneiform

Sumer is generally considered to be the earliest civilization (c. 5500–1800 BCE). As Sumerian society grew in complexity and established rich trade networks throughout Mesopotamia, the development of systems of record keeping and accounting became paramount. Previously Neolithic or tribal societies had less use for extensive systems of record keeping or even counting, and this is still true today. The Ös language of Central Siberia, for example, doesn’t have a word for thousand, which one speaker explained by saying, “In the olden days, our people never need to count a thousand things … so there’s no word for it.” (Harrison 2007: 189). The Yanoama language of the Amazon lacks words for numbers higher than 3 (Harrison 2007: 187). The Pirahã language of Brazil is famously claimed by linguist Daniel Everett to lack numbers entirely. Many languages spoken by small communities do have rich and complex systems of counting that reach very high numbers, however. Such complex systems just aren’t always necessary.

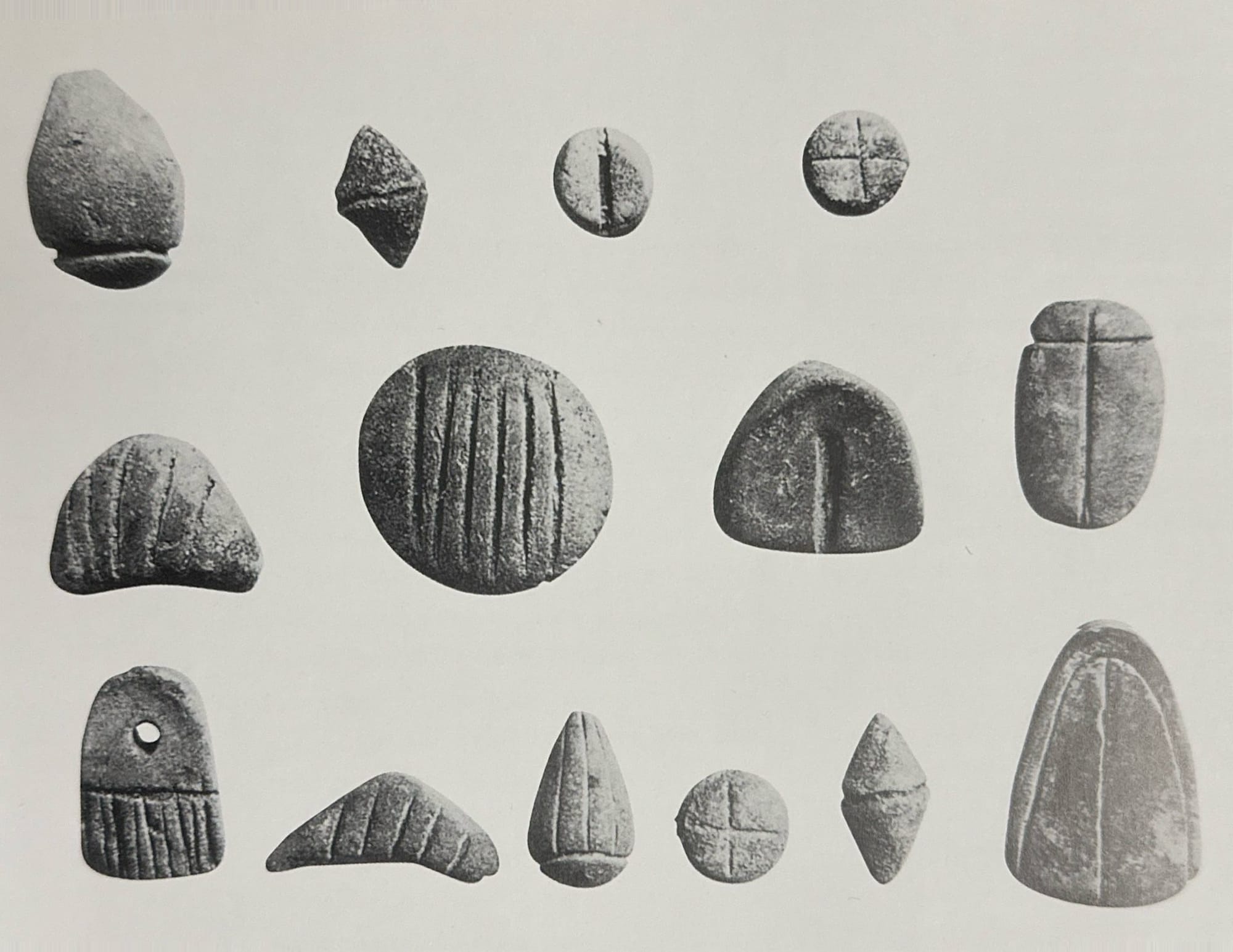

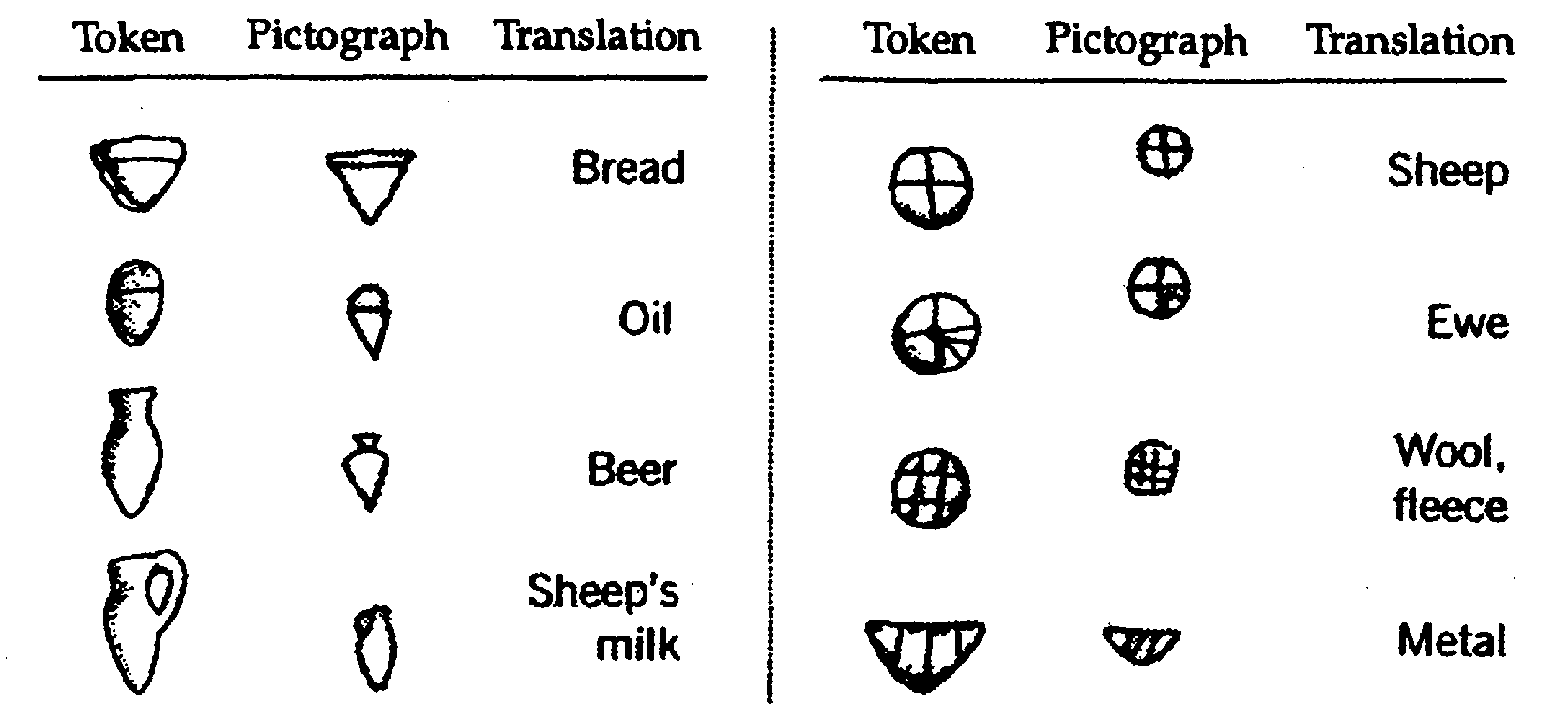

The growth of complex societies like Sumer, on the other hand, necessitates the use of extensive counting and tallying for the purposes of trade and administration, which is precisely why cuneiform evolved. Starting around 8000 BCE, clay “tokens” appear in the archaeological record in the Middle East—small, nondescript clay objects bearing tally marks (Figures 2–3). Differently-shaped tokens were used to tally different kinds of objects. For example, the crossed token seems to have been used to record numbers of sheep.

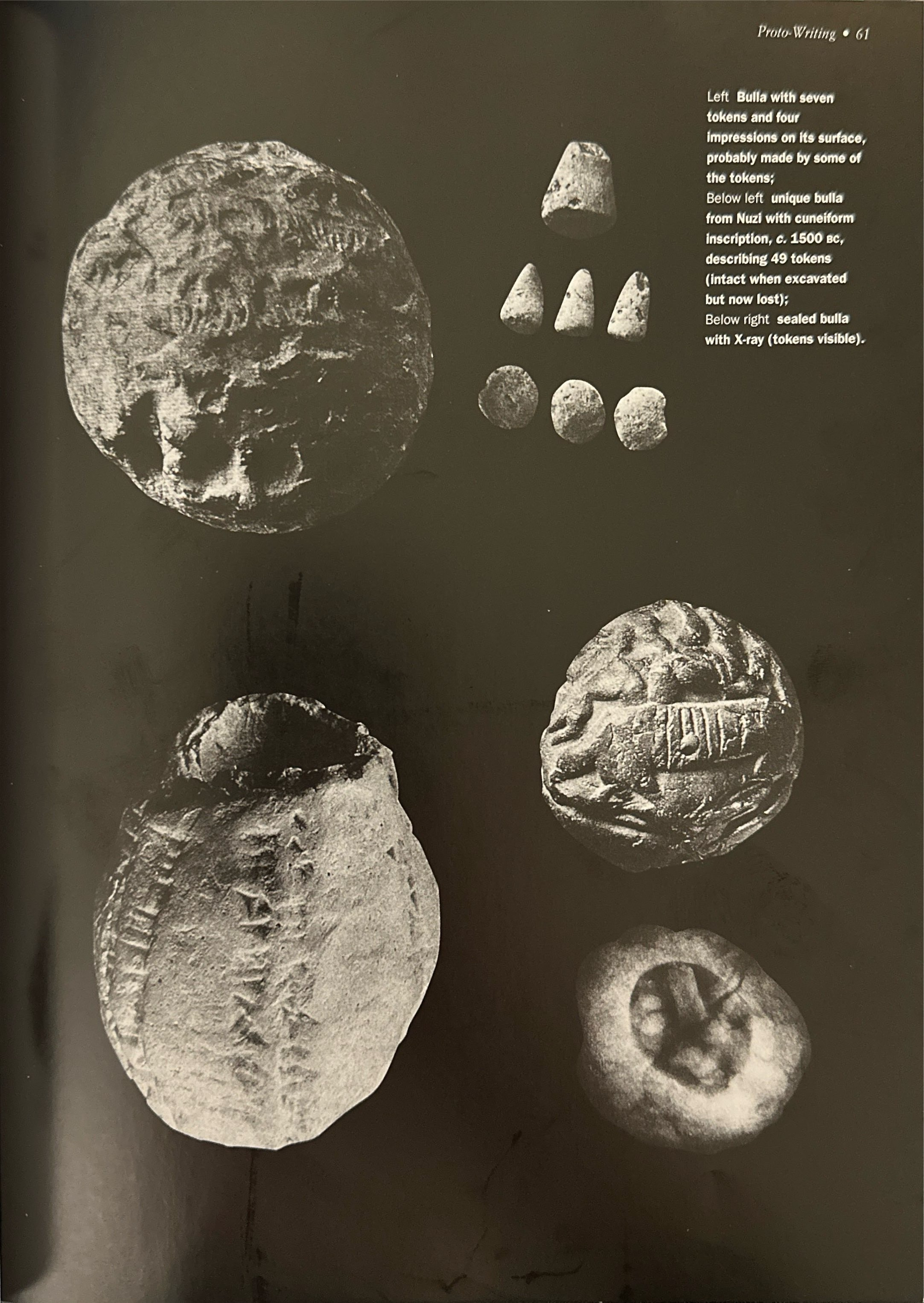

When shipping goods, merchants would enclose tokens in small spherical clay containers called bullae (Latin ‘bubble, blob’; see Figure 4). The recipient would then open the container to verify that the correct quantity of goods had been received.

Merchants later began impressing the token or a drawing of the token on the outside of the bulla, which obviated the need for the bulla in the first place. The merchant could simply send impressions of the symbols instead, leading to the earliest Sumerian pictographs. At least 30 Sumerian signs correspond closely to the shape of a specific token (Figure 5). Though 30 is a small number in comparison to the ~800 known proto-cuneiform signs, the correspondences nonetheless strongly suggest a connection (Coulmas 1996: 506–509; Gnanadesikan 2009: 15).

But while the use of bullae became more restricted, the pictographs grew in importance. Around 3300 BCE, the first proto-cuneiform tablets appear in the Sumerian city of Uruk. I say proto-cuneiform and not simply cuneiform because it was still not yet at a stage where it represented language. The difference between writing and proto-writing is that writing is a static representation of language, whereas proto-writing is a static representation of information that isn’t systematically related to a specific language. Tally marks, property/name marks, Incan quipu, certain types of cave paintings, and pictorial signs all generally fall under the term proto-writing (Coulmas 1996: 421).

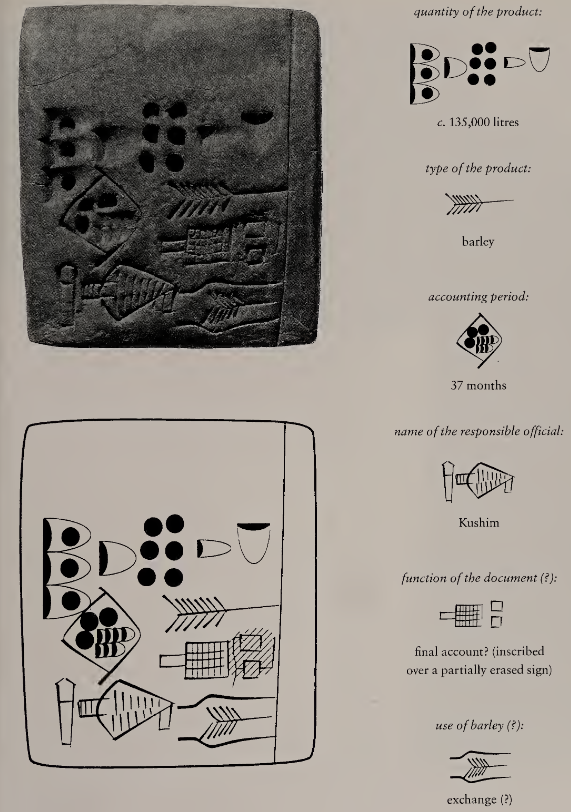

Proto-cuneiform texts are all numerical tablets concerning calculations and tallies of objects. (See Figure 7 for an example.) Of the total inventory of about 800 extant signs at the time, about 60 are numerals, and the rest are pictographic or quasi-pictographic (Gnanadesikan 2009: 15). They convey no grammatical information like verb tense or noun case, and there are no prefixes or suffixes. Because of this, scholars can’t be certain which language proto-cuneiform actually encoded (although Sumerian is usually assumed). A drawing of an ox could be read as the word ‘ox’ in any language. This illustrates why scholars call proto-cuneiform a type of proto-writing rather than writing.

The signs on proto-cuneiform tablets are arranged in boxes outlining the text, with one statement per box. The order of signs within a box tends to follow a specific pattern: the numerals, then the objects counted, and then other relevant information. So “3 sheep temple” might have meant that three sheep had been given to the temple. (Note that the order of the signs didn’t match the order of words in spoken Sumerian, again demonstrating why proto-cuneiform had not yet achieved the status of writing). (Gnanadesikan 2009: 18)

Sumerian Counting

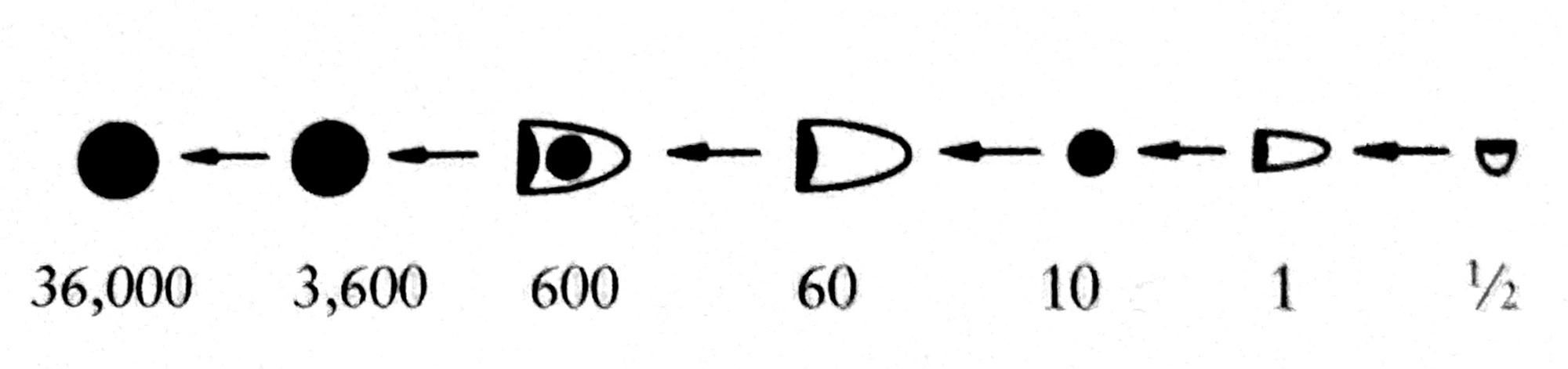

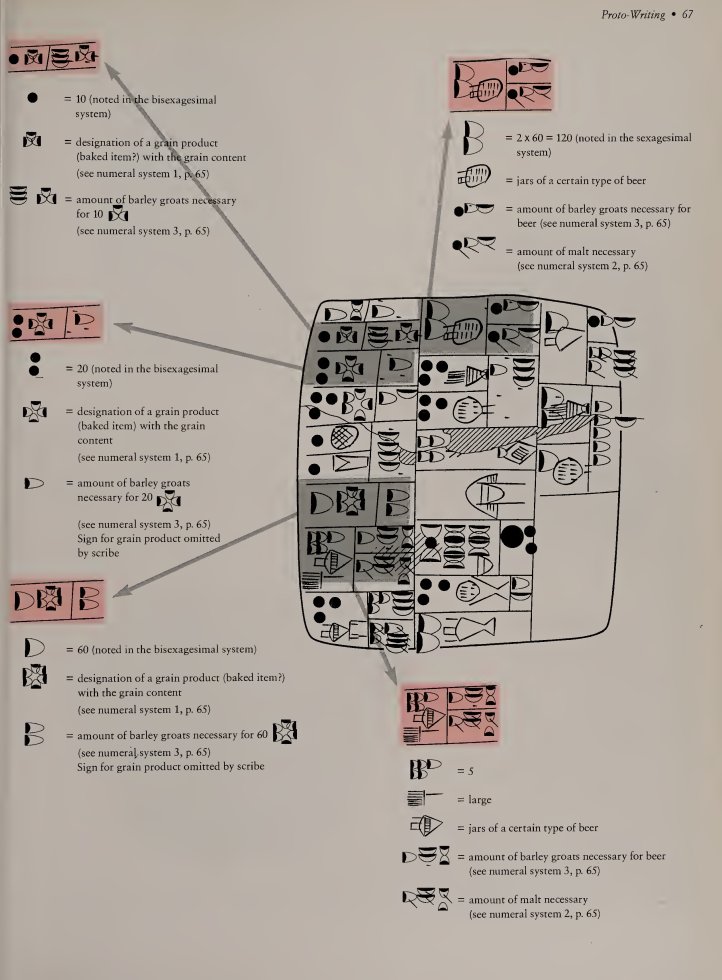

Even though proto-cuneiform was just used for counting, it was still incredibly complex. Different commodities used different measurement systems, and the system used changed with context. For example, here is one important series of numerals that was used to count many kinds of discrete objects:

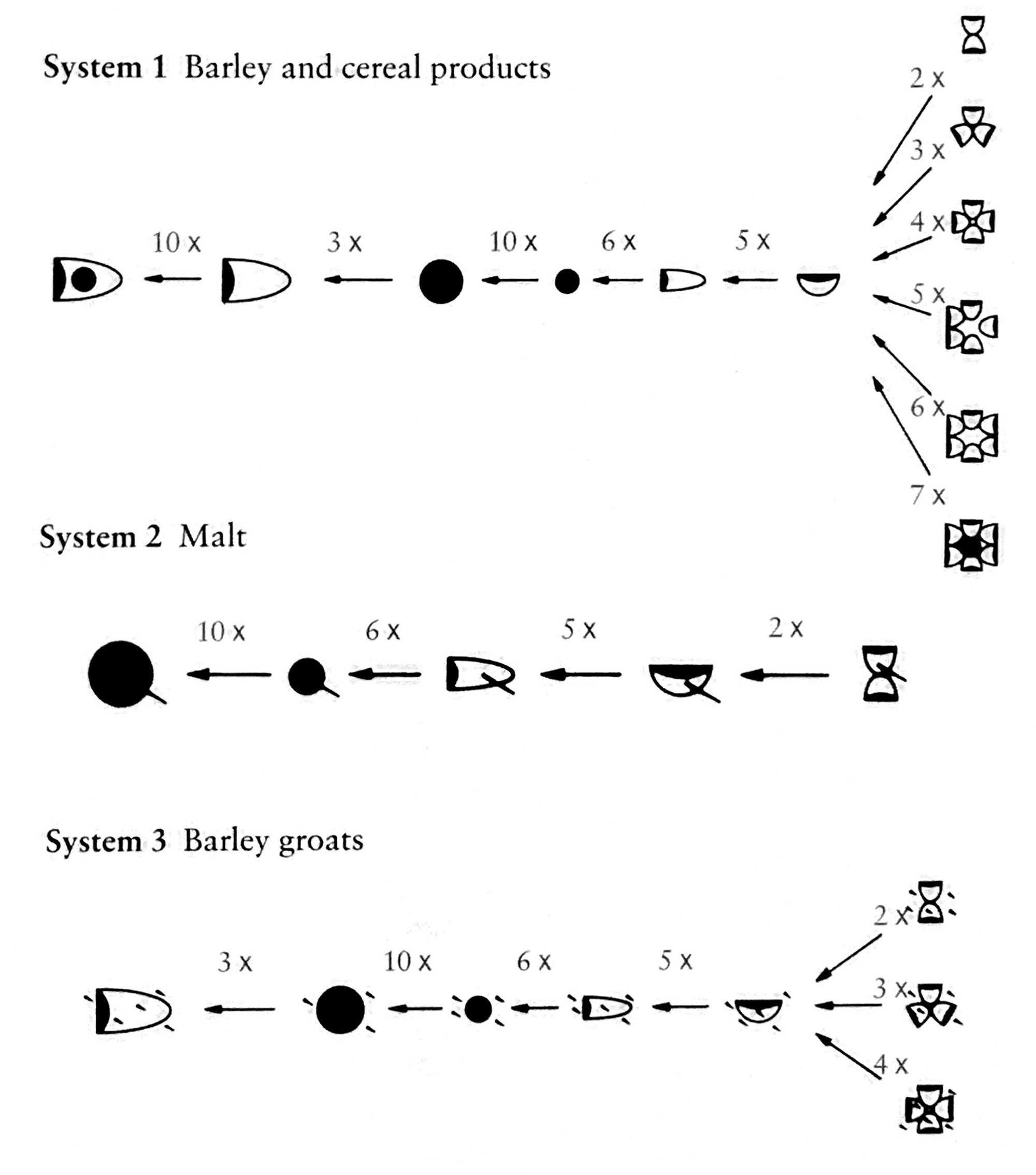

But different series of numerals were used to count barley and cereal products, malt, barley groats, land area, and calendar time. Readers had to surmise which series was intended based on context. Here are three of those series:

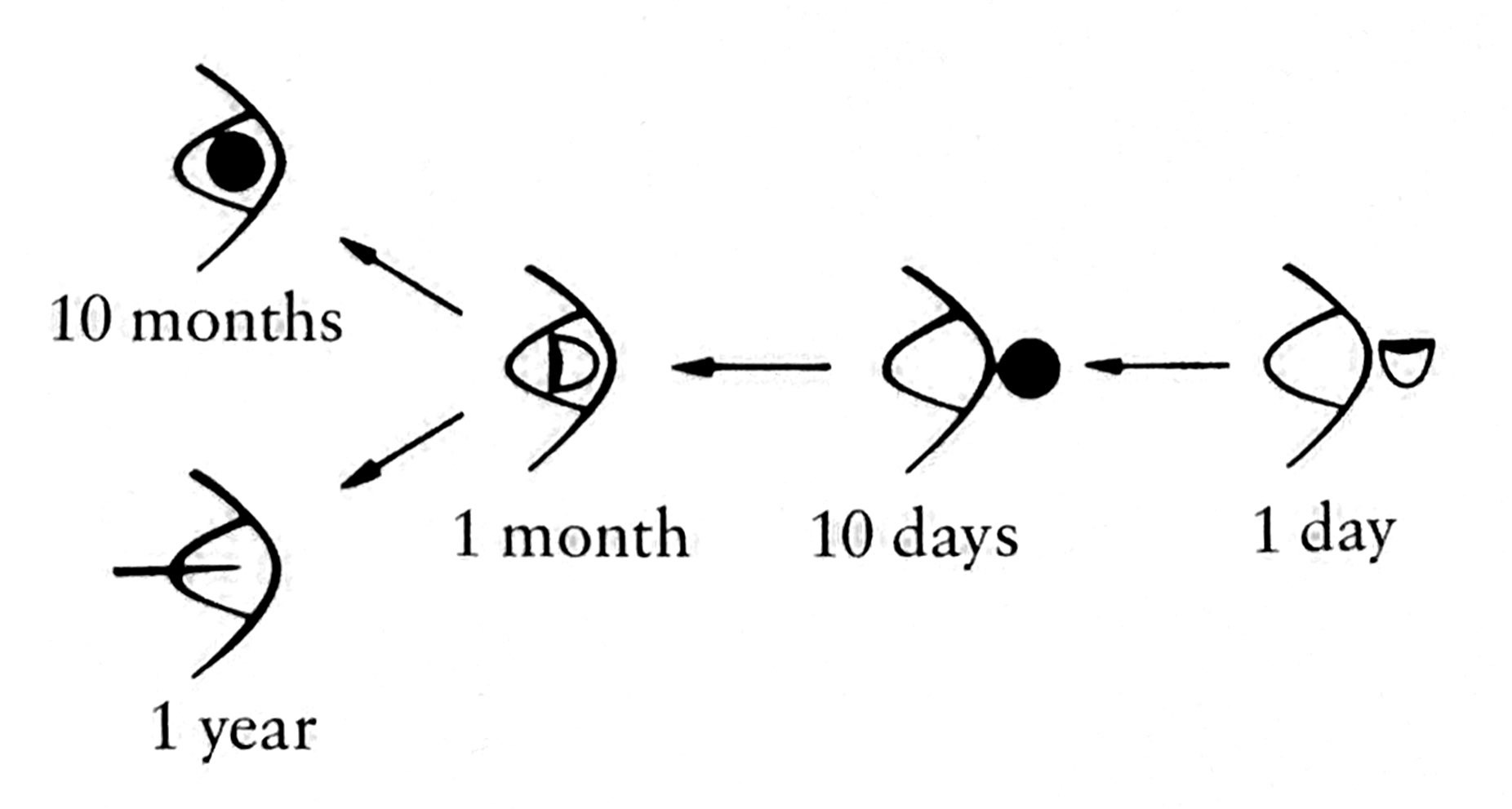

And here is the calendrical counting system:

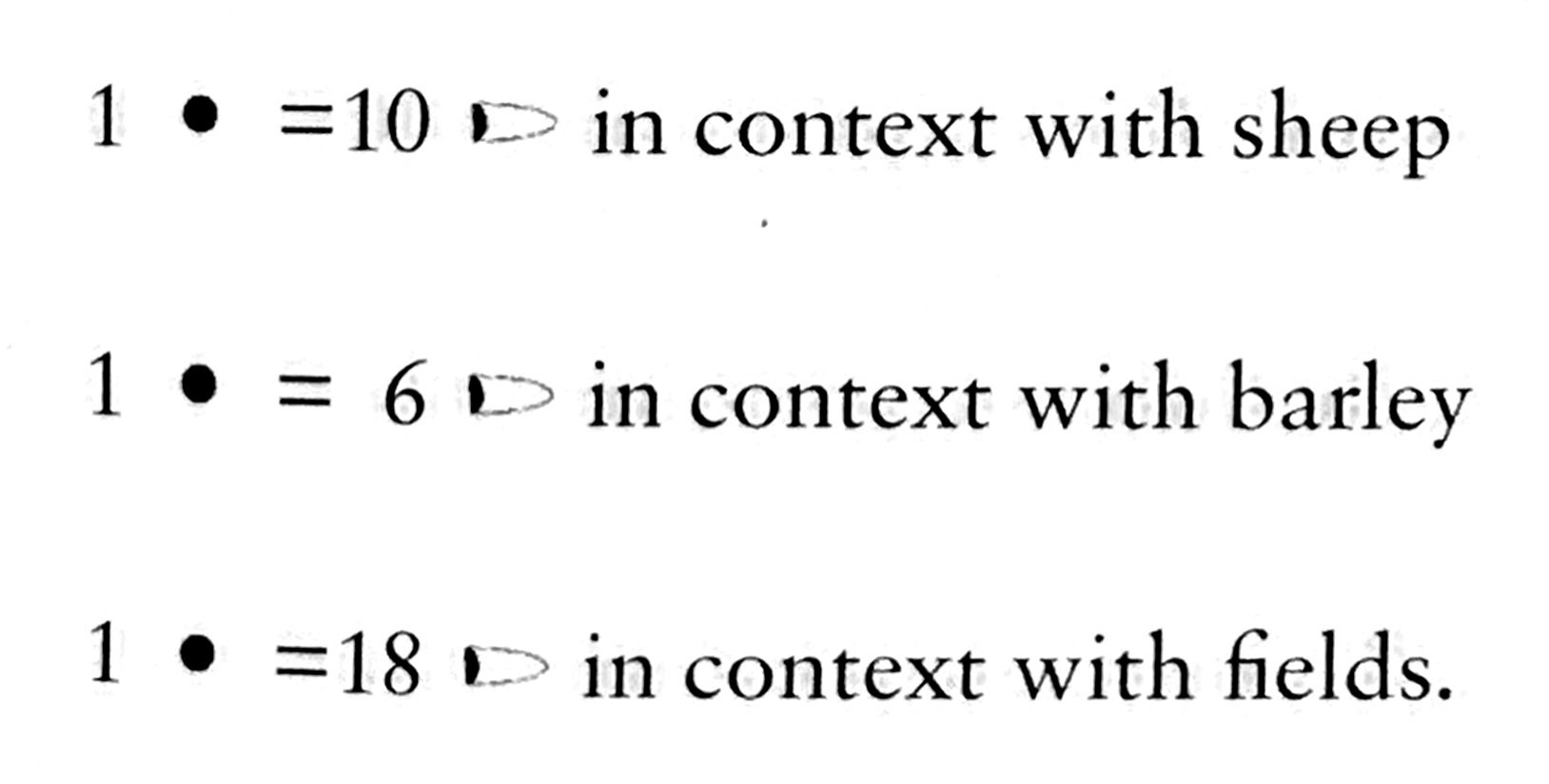

Because there were so many different systems, the value of an individual sign depends heavily on context. For example, the small dot changes its value depending on the type of item being counted:

To complicate things even further, some of these counting systems were base-60 (counting by 60s) while others were base-120 (counting by 120s)! These are called sexagesimal (by 60) and bisexagesimal (by 120) counting respectively. Here’s one example of a tablet using both systems:

Put simply, the early Sumerians did not yet use numbers fully abstractly. As Andrew Robinson states in his excellent book The story of writing:

The cardinal principle of our numeral system—that a numeral is an abstract entity that can be attached to anything from minutes to kilograms of cheese—had not been conceived by the earliest people to count. (Robinson 2007: 65)

From today’s standpoint, the proliferation of Sumerian counting systems seems like a deficiency, but it would be a mistake to interpret these tally systems through a presentist lens. Given that the primary function of these numeral systems was tallying objects, having numerals that tell you something about what is being counted would have been an advantage rather than a disadvantage (Gnanadesikan 2009: 15).

In fact, using different numerals to count different types of things isn’t too different from how English describes amounts of non-countable nouns: a glass of milk, a bushel of wheat, a pint of ale. The words glass, bushel, and pint in these expressions are called measure words. While English typically only requires measure words for uncountable nouns, other languages always use measure words when counting. One well-known example is Mandarin:

-

Mandarin

- 一yīone

- 只zhīcl

- 狗gǒudog

‘one dog’

-

Mandarin

- 三sānthree

- 只zhīcl

- 狗gǒudog

‘three dogs’

So the Sumerian system of using different counters for different types of objects is not as exotic as it may at first seem.

Babylonian Mathematics

Over time, however, the Sumerian counting system—and indeed all the signs—did eventually simplify. Scribes began to write using a wedge-shaped stylus, giving the signs their distinctive wedges. The signs became more abstract and were less iconic/pictographic. Here is how the sign for ‘head’ evolved over the 2,000-year period from 3000 BCE to 1000 BCE:

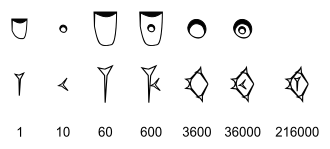

Remember that base-60 system for counting discrete objects in proto-cuneiform? That system won out and became the standard system of counting in Sumerian. Here’s what that same system looked like about 800 years later, c. 2500 BCE. (Note that the symbols are in reverse order from Figure 8.)

Around this time, the Sumerian language was being displaced by Akkadian, the earliest documented Semitic language. Akkadian was the language of the Akkadian Empire, which had succeeded the civilization of Sumer. The Akkadians adapted the Sumerian writing system to their language and continued to use its system of counting, with modifications. The Akkadian language then diverged into two dialects, known as Assyrian and Babylonian. Interestingly, even though the Assyrian/Babylonian language used a base-10 counting system rather than a base-60 counting system in speech, they kept the base-60 counting system of the Sumerians in writing, and just used 10 as a subbase—a testament to how strongly the Sumerians had influenced their culture. Here is what that Old Babylonian counting system looked like:

| Num. | Sign | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 𒐕 | 11 | 𒌋𒐕 | 21 | 𒎙𒐕 | 31 | 𒌍𒐕 | 41 | 𒐏𒐕 | 51 | 𒐐𒐕 |

| 2 | 𒐖 | 12 | 𒌋𒐖 | 22 | 𒎙𒐖 | 32 | 𒌍𒐖 | 42 | 𒐏𒐖 | 52 | 𒐐𒐖 |

| 3 | 𒐗 | 13 | 𒌋𒐗 | 23 | 𒎙𒐗 | 33 | 𒌍𒐗 | 43 | 𒐏𒐗 | 53 | 𒐐𒐗 |

| 4 | 𒐼 | 14 | 𒌋𒐼 | 24 | 𒎙𒐼 | 34 | 𒌍𒐼 | 44 | 𒐏𒐼 | 54 | 𒐐𒐼 |

| 5 | 𒐊 | 15 | 𒌋𒐊 | 25 | 𒎙𒐊 | 35 | 𒌍𒐊 | 45 | 𒐏𒐊 | 55 | 𒐐𒐊 |

| 6 | 𒐚 | 16 | 𒌋𒐚 | 26 | 𒎙𒐚 | 36 | 𒌍𒐚 | 46 | 𒐏𒐚 | 56 | 𒐐𒐚 |

| 7 | 𒑂 | 17 | 𒌋𒑂 | 27 | 𒎙𒑂 | 37 | 𒌍𒑂 | 47 | 𒐏𒑂 | 57 | 𒐐𒑂 |

| 8 | 𒑄 | 18 | 𒌋𒑄 | 28 | 𒎙𒑄 | 38 | 𒌍𒑄 | 48 | 𒐏𒑄 | 58 | 𒐐𒑄 |

| 9 | 𒑆 | 19 | 𒌋𒑆 | 29 | 𒎙𒑆 | 39 | 𒌍𒑆 | 49 | 𒐏𒑆 | 59 | 𒐐𒑆 |

| 10 | 𒌋 | 20 | 𒎙 | 30 | 𒌍 | 40 | 𒐏 | 50 | 𒐐 | 60 | 𒐑 or 𒐕 |

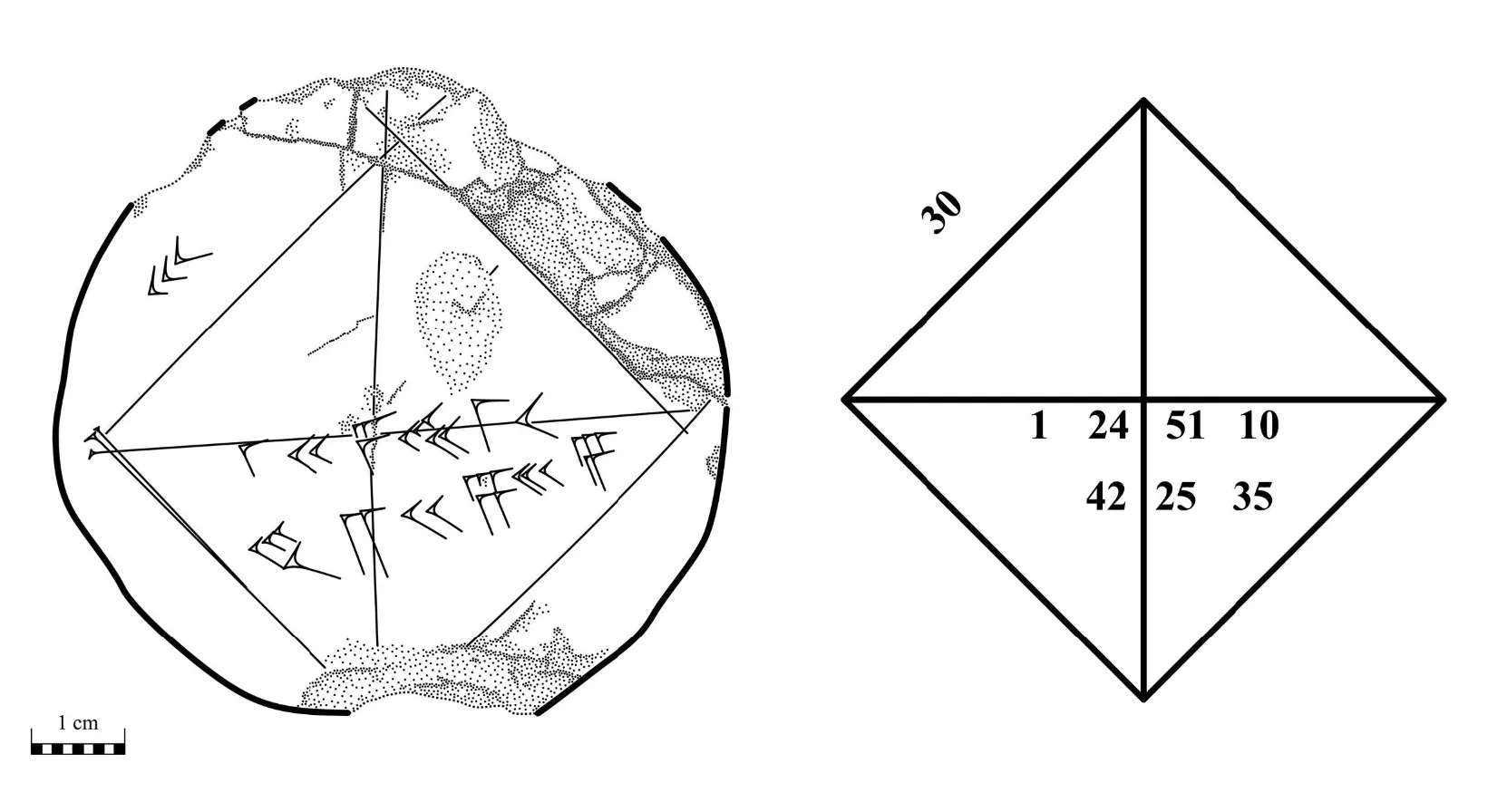

By this point the numeral system had developed into a place value system, where the value of a numeral depends on its position within a number. This is just like how the Arabic numeral system works today. In the Arabic numeral system, each 4 in the number 444 has a different value—400 in the first position, 40 in the second position, and 4 in the third. The Babylonian system worked the same way, with two major differences: a) it had a base (or radix) of 60, and b) it lacked a symbol for 0. The lack of a sign for 0 made most numerals highly ambiguous. Babylonian scribes would have had to keep in mind an empty space within numbers when doing calculations.

For example, the sign 𒐕 could represent 1, 60, or 3,600, depending on whether it was interpreted as having one, two, or no zeros after it. Likewise, the sign 𒌋 could represent 10, 600, or 36,000. They could even represent fractions! 𒐕 could also be 1/60, 1/3,600, etc. Here are two examples showing the different ways a single number could be interpreted (from Robinson 2007: 86–87):

-

𒐕𒌋𒐊

-

-

𒐖𒐏𒐊

-

Despite the ambiguity caused by the lack of zero, this was nonetheless the first positional numeral system, and it would have an enduring influence throughout history, as we’ll see.

The Babylonian Influence Today

Using the base-60 numeral system inherited from the Sumerians, the Babylonians made great advances in mathematics,

including topics in fractions, algebra, quadratic and cubic equations, and the Pythagorean theorem. One well-known

tablet dated to c. 1800–1600 BCE calculates

It is because of the Babylonians and their advanced study of mathematics that an hour has 60 minutes and a minute has 60 seconds today. This system was devised by the Greek astronomer Eratosthenes (c. 276–194 BCE), who followed in a long tradition of using astronomical techniques originally developed by the Babylonians. He created an early geographic system of longitude that divided a circle into 60 parts. A century later, Greek astronomer Hipparchus (c. 190–120 BCE) subdivided each of the 360 degrees of longitude into smaller segments. He labeled the first subdivision ‘the first small parts’ and the second subdivision ‘the second small parts’. Those were translated into Latin as partēs minūtae prīmae and partēs minūtae secundae respectively. Eventually the first subdivision came to be known as simply the minute, and the second subdivision the second.

There may also be some more subtle influences. In many Indo-European languages, numbers behave differently after 60. In Old English, for example, the word for 60 was siextiġ (> Modern English sixty), but the word for 70 was hundseofontiġ, literally ‘ten-seven-ty’, where hund- meant ‘10’ and is related to hundred. French famously switches to something akin to a base-20 counting system after 60: 60 is soixante, but 70 is soixante-dix, literally ‘sixty-ten’ instead of septante as would be expected in a pure decimal system. It is possible (but not at all proven) that this break at 60 in these languages is due to the lasting influence of the Sumerians and the cultural importance of 60.

And that is the story of how a tally system of proto-writing that began perhaps as far back as 10,000 years ago still guides our modern mathematical techniques and methods of telling time.

📖 Recommended Reading

📑 References

- Comrie, Bernard. 2013. Numeral bases. In World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. http://wals.info/chapter/131.

- Coulmas, Florian (ed.). 1996. The Blackwell encyclopedia of writing systems. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gnanadesikan, Amalia E. 2009. The writing revolution: Cuneiform to the internet (The Language Library). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Harrison, K. David. 2007. When languages die: The extinction of the world’s languages and the erosion of human knowledge. Oxford University Press.

- Nissen, Hans J., Peter Damerow & Robert K. Englund. 1993. Archaic bookkeeping: Early writing and techniques of economic administration in the Ancient Near East. University of Chicago Press.

- Robinson, Andrew. 2007. The story of writing: Alphabets, hieroglyphs, and pictograms. 2nd edn. Thames & Hudson.

- Schmandt-Besserat, Denise. 1992. Before writing. 2 vols. University of Texas Press.

If you'd like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.