Where does the alphabet come from? And why does English use it so strangely?

A new book takes us on a linguistic odyssey through the history of the alphabet

It is a sunny day, and a man takes shelter from the heat in a street not far from the east bank of the river Nile. Between the houses, he can catch glimpses of that mighty river, full of ships travelling up and down. He, a humble merchant, had himself arrived by one such boat, travelling upriver to visit this city of Thebes, which is prosperous and bustling.

The crowds increase as he walks towards the temple of the god Amun, where he is to meet with a potential client. The temple is a grand site with royal patronage, having been constructed on the orders of pharaoh Senusret I himself. The current ruler is Amenemhat III, and Egypt is enjoying a state of unity and stability that historians of the future will call its Middle Kingdom, 1,800 years before Christ—not that our merchant thinks of his day and age as being ‘before’ anyone or anything.

Looking up at the great temples, statues and obelisks, it is clear to the visitor that these Egyptians are a highly literate people; the buildings are covered with hieroglyphs, many painted and carved with painstaking detail.

These are official inscriptions intended to impress and to endure, existing somewhere between writing and art. However, when he had stopped at a tavern for a drink, the visitor had also seen people writing in a more casual style, composing messages and lists with a brush, ink and papyrus.

The local language is Egyptian, which our visitor to Thebes understands and speaks pretty well, but the written language remains tricky. Having been around for over a thousand years, this system of pictures and symbols is sophisticated and complex. He knows that some hieroglyphs simply stand for a particular object or idea, the thing that they appear to represent. Others stand for a sound, or two sounds together, or even three. Others are used instead to tell you something about the type of the thing that precedes them—whether it is a man or a woman, a god, a building, a drink, a boat. To complicate matters, in principle, a given hieroglyph can be put to all three of these uses in different contexts and by different scribes. Moreover, the number of hieroglyphs that the Egyptians use seems beyond count; future experts will reckon around 700. Try as he might, Egyptian writing still makes the visitor’s head spin.

He himself is not Egyptian. His origins lie far to the north-east, beyond the kingdom of the Nile, and his mother tongue is very different. What he and his people speak is one dialect of an expanding family of languages that will one day include internationally famous members, such as Arabic and Hebrew. His people can be found throughout Egypt, though especially concentrated in Lower Egypt, where the Nile spills out into the Mediterranean, and where he has set up a business trading papyrus. Many of his people have been employed by the Egyptians as soldiers and servants. Though he lives and works among the Egyptians, the visitor is a linguistic outsider to this complex world of hieroglyphs and the Egyptian language that they write down. Their symbols and speech share an ancient association, while his own language is a newcomer on the scene. If he wants to write in his language, not theirs, he and his people must either invent their own writing system from scratch, or adapt the Egyptians’ characters. They are opting for the latter. Their adaptation has already begun, and with it, the first shoot of a new tree of writing is sprouting.

With his business in Thebes concluded, our visitor begins his return journey northwards. However, this time, rather than sailing along the Nile around the Qena Bend, he chooses to cut a corner and take the Farshût road over land. It’s a sensible decision; it’s quicker, and the waters of the Nile can be difficult and unkind. The route takes him away though from the lush, green landscape of the Nile valley and off into wilder land. Halfway through this shortcut, the man stops in a valley that will be known in Arabic as Wadi el-Hol. There he chats to his travelling companions, eats and drinks with them and takes a break from the journey. Wadi el-Hol is a popular spot; soldiers, pilgrims and merchants are all passing through, and many people have left behind messages in the surrounding limestone rock.

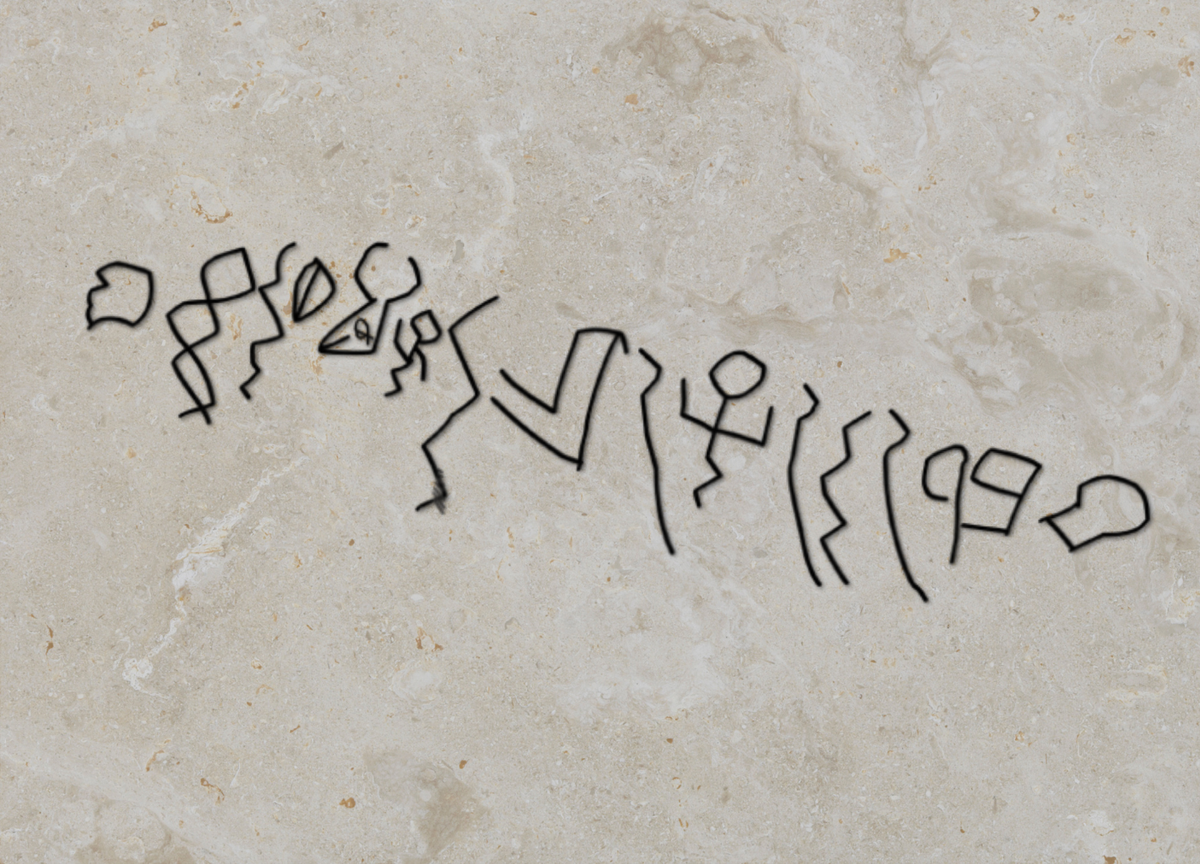

To pass the time, the man decides to add to the lithic literature. Rather than in the Egyptians’ formal hieroglyphs, or their more casual ‘hieratic’ script, he carves from right to left 16 hieroglyph-like symbols that work according to a much newer system. It is something his people have been developing recently, and it is not the first example at Wadi el-Hol; he spots a previous message by a fellow compatriot, written instead from top to bottom.

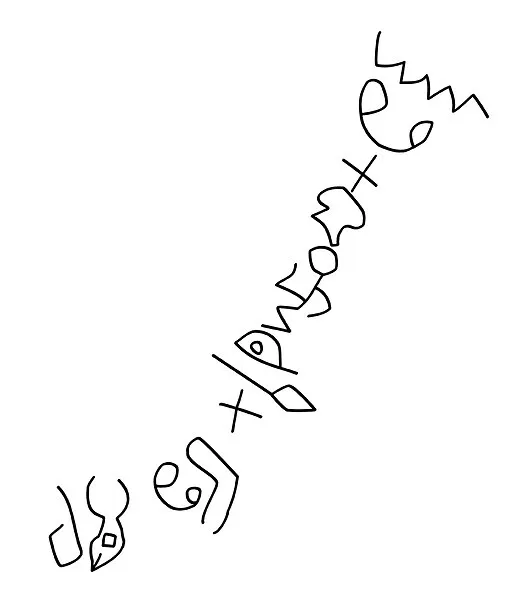

Compared with the complexities of hieroglyphs, the principle behind the man’s system is simple: every image looks like a thing, and it stands for the first sound of the word for that thing in his language. For example, he carves an ox’s head, with eyes and horns, facing to the left:

For him, an ox is a ʾalp. The word ʾalp begins with a glottal stop. This is a sound produced when the glottis, an opening between the vocal folds in our throats, quickly closes then opens. In doing so, it briefly stops any exiting airflow. It’s a very common sound in speech, made when English speakers for example will say uh-oh. The traveller’s revolutionary principle says that, because the word for an ox begins with a glottal stop, the symbol of an ox now stands for that sound. No more ambiguities about whether the symbol refers to a thing, an idea, a category, a sound, two sounds, three sounds—just one symbol, for one sound.

His inscription completed and his companions well rested, the man continues on his way north, and so vanishes from history and our imagination. In truth, we know nothing about the individuals who carved the two inscriptions in the new script at Wadi el-Hol, nothing certain about their origins, languages, profession, status or gender. All we have is what they left behind there, but it’s enough to know that they were part of something big. Over the course of almost 4,000 years, that head of cattle would develop beyond recognition and travel far, all the way to this very text. Its horns would become a letter’s legs, and its mouth would come to point upwards.

It would become our letter A.

This short narrative is the opening section of ‘Chapter A’ in Why Q Needs U, a new book about the history of the alphabet and how we today spell the English language. It sets out to answer, in an accessible and entertaining style, two broad questions. First, where did we get the alphabet from? Second, why does English use it in such a strange way?

To tackle the first topic, Why Q Needs U starts off in Ancient Egypt. It assembles the story of the alphabet’s birth from ancient fragments of text and modern academic scholarship. The new principle mentioned in that story is a milestone in human history; it was a deliberate departure from the Egyptian tradition of writing, and so launched a new tradition that has endured all the way up to the very letters that your eyes are reading right now. We humans as a species come out well from this story, because it shines a light on our shared linguistic ingenuity. The evidence suggests that the alphabet’s ancient innovators were humble people, whose status as ethno-linguistic outsiders in the Kingdom of Egypt motivated their repurposing of old symbols. They understood the value of writing, what it offered their speech. They also understood what in the new medium their language needed to have represented, if it was to be written down and read successfully.

Clearly, though, from those first sparks of alphabetic fire, our letters have a long way to go—our capital letter A definitely doesn’t look like an ox’s head anymore! To tell the full tale, Why Q Needs U spends time with each character in the cast of this long story. For instance, Chapter A goes on to track the alphabet’s anti-clockwise journey around the Mediterranean Sea, until it lands in the hands of the Greeks. It was in Greece that A was reassigned to represent a vowel sound, no longer a glottal stop. It was also in Greece that a left-to-right direction of writing first won out, having fought off the older right-to-left direction that Arabic and Hebrew still go by today. This shift, and its possible psychological origins, are discussed in Chapter B.

Indeed, every letter is a chance to explore some aspect of the international collaborative project that is the alphabet. Some of the chapters of Why Q Needs U spend time with certain peoples who have played a part in how we now spell English; Chapter C exalts the Etruscans, while Chapter K acknowledges the linguistic imports of the Vikings. Other chapters, like Chapters G, J and P, look at how specific individuals can leave a lasting legacy, if the societal conditions are right. Others, like Chapters O and V, look at the multi-faceted shape of the English language, with all its different dialects and disagreements in sound. Letters like E, H and N invite us in their chapters to step back and admire ingenious systems quietly at work in how we spell, such as the matter of doubled consonant letters that assist in the spelling of the vowel that they follow.

Why Q Needs U is a linguistic love letter to language, speech and spelling, and an attempt to capture in one book the world of human experience behind our letters, from A to Z.