Libfixes: When word parts go rogue

What happens when parts of words declare independence

There’s a revolution happening in English, and the affixes are winning. They’re breaking free from their original words, declaring independence, and forming new allegiances. ‑cation no longer belongs to vacation; ‑pocalypse has abandoned apocalypse; ‑flation has defected from inflation. Now they league with the likes of staycation, snowpocalypse, and stagflation. The affixes have been liberated. Call it what you want—Affixgate, Affexit, Affixception—but in linguistics these rogue word parts are known as libfixes (‘liberated affixes’), and today I’m providing you with some linguotainment about these unusual words in this first of a 2-part series.

ℹ️ Articles in this Series

- Part 1: Libfixes: When word parts go rogue [this issue]

- Part 2: The science of libfixes: How libfixes work, where they come from, and what they teach us about language and the mind

This article contains a number of sexually explicit and derogatory terms (but not pictures or videos). These terms are included here solely for educational purposes and are merely discussed, not used with their normal pragmatic intent. (See the Use-Mention Distinction for more on this difference.) Nonetheless, you may want to screen this article before sharing it with kids, and/or exercise judgement if viewing this at work.

No Longer Bound: The Libfix Revolution

The fateful day came in 1965, when an unwitting English speaker, perhaps influenced by words like ethanol into thinking that alcoholic too contained the suffix ‑ol, rent the word alcohol asunder, cast down the beginning alco‑, and in a flash of creative insight coined a strange new frankenword: sugarholic.

The ‑holic in chocoholic and shopaholic and workaholic didn’t start out free. Its path to liberation was long and circuitous: It began its life in the depths of history as the Akkadian word guḫlum, referring to a lustrous gray mineral we today call stibnite. Traditionally, stibnite was reduced to a cosmetic powder called kohl that was then used to darken the skin around the eyes. Thus the word guḫlum could refer to either the mineral or the cosmetic powder. Aramaic later borrowed this word as kuḥlā, and Arabic then borrowed it from Aramaic as the word كُحْل kuḥl sometime during the Old Arabic period (c. 1st millennium BCE) (Wiktionary: كحل).

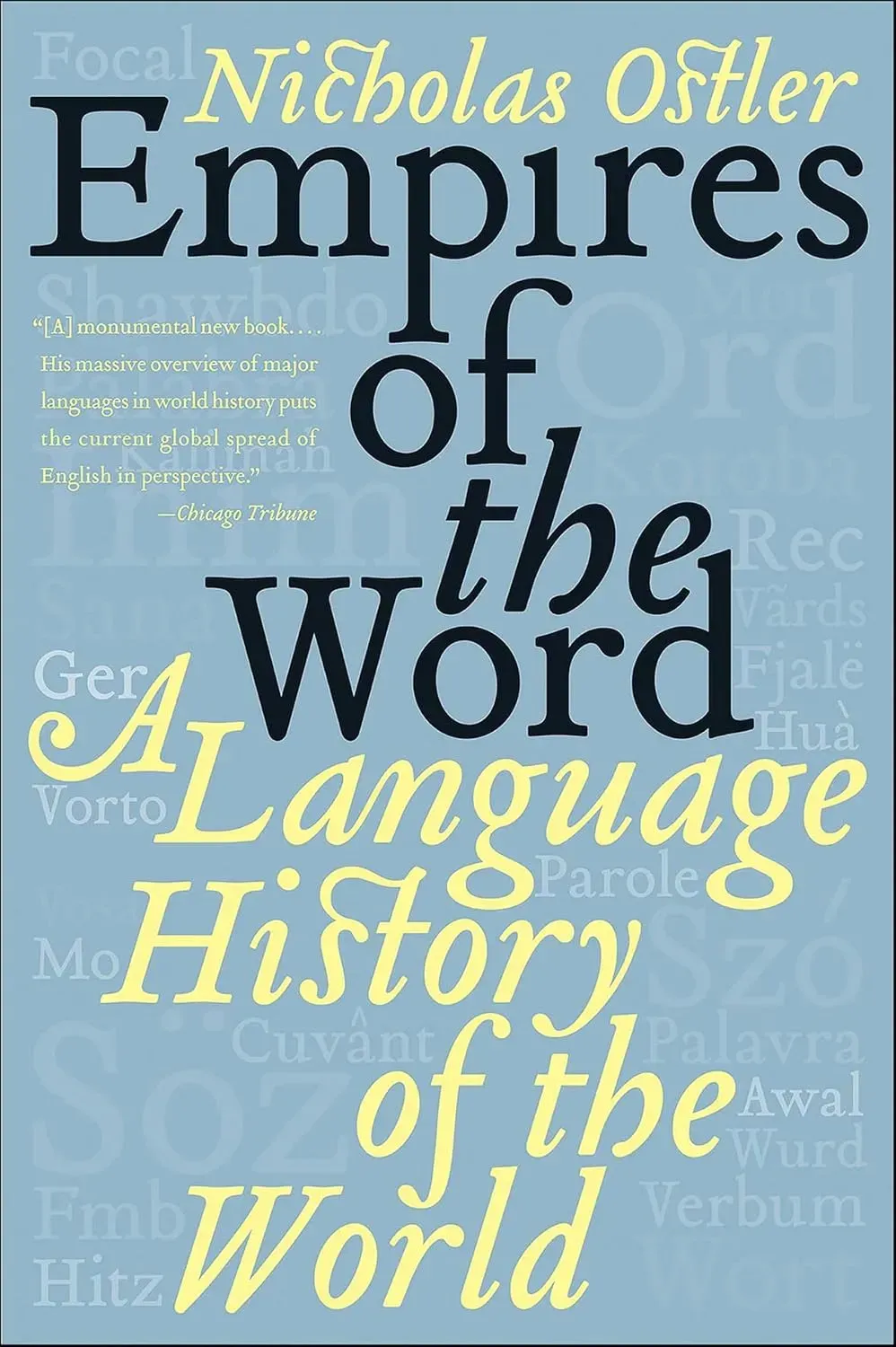

The Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula by the Umayyad Caliphate brought the word with it in the form of Andalusian Arabic كُحُول kuḥūl (Wiktionary: alcohol). This period was the beginning of the Islamic Golden Age as well as the Islamic–European knowledge exchange, when the Islamic world contributed significantly to the intellectual advancement of Europe. These contributions came in many forms, including Latin translations of previously lost Ancient Greek texts (like Aristotle), and numerous Arabic texts in astronomy, mathematics, science, and medicine. Many technical terms in English originate from words borrowed from Arabic during this period: algebra, algorithm, chemistry, cipher, zero, zenith, and many others.

Among those words was alcohol, the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic phrase اَلْكُحُول al-kuḥūl ‘the kohl’. al‑ is the definite article ‘the’ in Arabic, but many European scholars mistook it as part of the following word, which is why so many Arabic borrowings in European languages begin with a‑ or al‑ (e.g. Spanish azúcar ‘sugar’ and algodón ‘cotton’). In Medieval Latin alcohol initially referred only to kohl, the cosmetic powder, but soon it took on a more generic meaning, referring to any powder obtained from titrating a material. This was the meaning it had when it was subsequently borrowed into Spanish and French.

English got ahold of the word in the 1540s from either Spanish, French, or Medieval Latin, and it quickly expanded in meaning to not just powders but distillates of liquids as well. By the 1670s, alcohol could refer to any sublimated substance, or metaphorically to the “essence” or “spirit” of anything. The first use of the modern sense of the word, referring to intoxicating beverages, appears in 1753 in the phrase “alcohol of wine”. (Barnhart 1988: 22–23; Etymonline: alcohol)

‑holic entered its captivity in 1790 when the word alcoholic first appears in the record. At the time, the word simply meant ‘of or pertaining to alcohol’. The meaning ‘caused by drunkenness’ is attested in 1872, and finally the modern sense of ‘habitually drunk’ in 1910. It was at this point that a fortuitous coincidence occurred: just a few years prior, the International Conference on Chemical Nomenclature resolved to name alcohols using a shortened form of the word alcohol as a suffix, ‑ol, coining terms like ethanol (ethyl alcohol), methanol (methyl alcohol), and phenol (benzine alcohol) (Wikipedia: Ethanol). (Those coinages also include an infix ‑an‑ meaning ‘a single bond’.) Suddenly, ‑ol was a productive suffix that could be used to form new words at will, and in this suffix ‑holic received its first glimpse of freedom. If ‑ol could run wild, attaching itself to any word it pleased, why couldn’t the adjective form ‑(h)olic?

The fateful day came in 1965, when an unwitting English speaker, perhaps influenced by words like ethanol into thinking that alcoholic too contained the suffix ‑ol, rent the word alcohol asunder, cast down the beginning alco‑, and in a flash of creative insight coined a strange new frankenword: sugarholic.

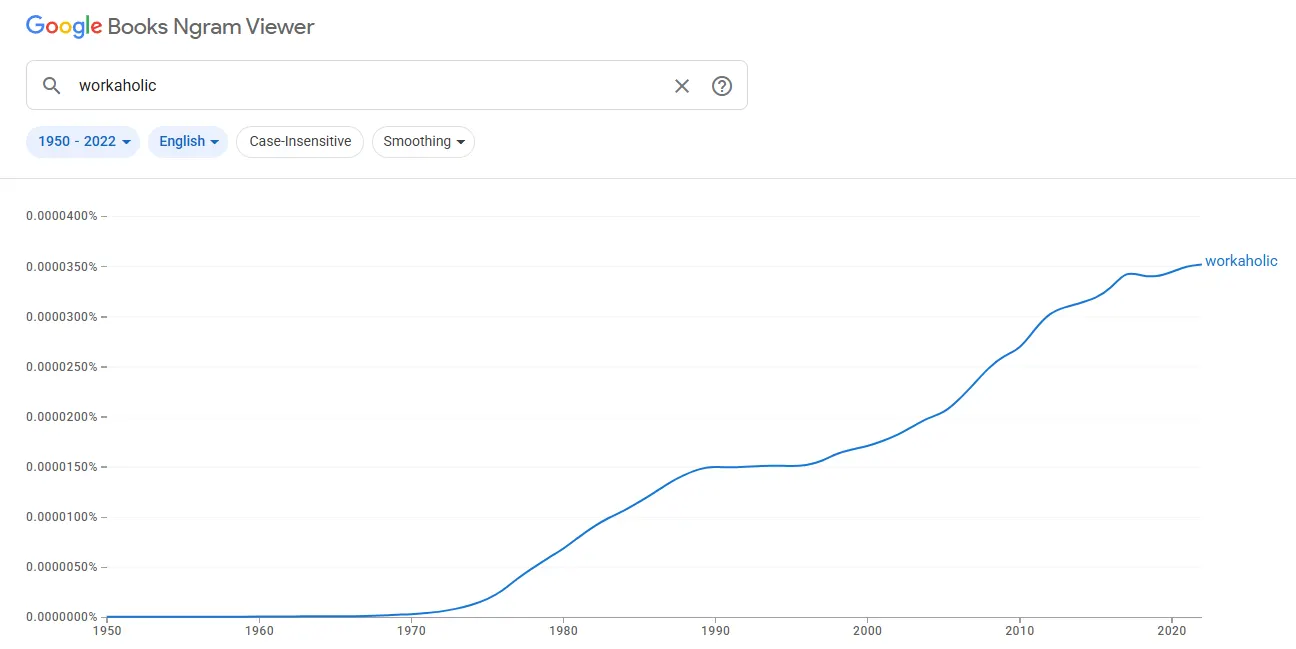

After centuries of captivity, ‑holic seized upon its chance and was at last free. Within the year it had formed an alliance with food to create foodoholic, and in 1968 it achieved its masterstroke: workaholic. This confederation proved to be unstoppable, rocketing ‑holic to such heights that it would never have to worry about lexical captivity again:

With the model of workaholic deeply entrenched and popularized, other words soon fell into line: golf and chocolate succumbed quickly as golfaholic and chocoholic in 1971, then shopping as shopaholic in 1984 (Etymonline: -aholic). Today there are entire Wikipedia pages filled with ‑holic offspring, a testament to its ascendancy.

What are libfixes?

“So, if you’re a really dedicated coffee artist and you really put your whole baristaussy into this latte, I’m expecting some killer latte art.” ~ Kirby Conrad, Ph.D.

The etymological history in the previous section illustrates several common types of language change:

- borrowing words between languages, which often involves adapting the pronunciation of the word to the new language (termed phonological adaptation), e.g. Andalusian Arabic al-kuḥūl → Medieval Latin alcohol, where Latin replaced the foreign ⟨ḥ⟩ (voiceless pharyngeal fricative /ħ/) sound with native /h/.

- rebracketing, where the boundaries of words or affixes are reanalyzed. In the case of al-kuḥūl becoming alcohol, the boundary was lost entirely, a process called juncture loss.

- blending, combining parts of two or more words, such as ethyl + alcohol → ethanol.

- libfixation, the focus of today’s article, when parts of words escape their parent words and become new affixes.

If any of the abbreviations or notations in this article are unfamiliar to you, check out the “How to read linguistics” page. It lists all the abbreviations, conventions, and notations used in Linguistic Discovery content.

The term libfix was first coined by linguist Arnold Zwicky on his blog in 2010 and defined as follows:

The “liberation” of parts of words […] to yield word-forming elements that are semantically like the elements of compounds but are affix-like in that they are typically bound. (Arnold Zwicky’s blog: Libfixes)

The word itself is a blend of liberated affix, and follows the pattern of other affix names in linguistics: prefix, suffix, circumfix, infix, and others. Other terms used to describe libfixes include fragment, secreted affix (gross), combining form, and splinter (see Delhem & Marty 2024: 5 for sources).

The best-known libfix is ‑gate, originally part of Watergate, the name of a hotel where an infamous political scandal involving former US President Richard Nixon occurred in the early 1970s. The episode quickly became known as “the Watergate scandal”, and soon commentators were using that phrase as a template for creating other neologisms like Volgagate (in a 1973 article in National Lampoon; OED: ‑gate). New York Times columnist William Safire popularized the construction soon after, writing about Vietgate in September 1974, and then applying the pattern with abandon: Billygate, Briefingate, Contragate, Debategate, Lancegate, Nannygate, Raidergate, and many others. His intention may have been to “minimize the relative importance of the crimes committed by his former boss with this silliness” (source), but the inadvertent effect of his sarcastic use of ‑gate was to ensconce the suffix in public consciousness. Today ‑gate is used for all manner of scandals and controversies, with a giant Wikipedia list dedicated to its appearances in English. Some examples from recent memory include gamergate, nipplegate, emailgate, and poopgate (which will forever be part of local Chicago lore—but don’t let it deter you from doing the fantastic architectural boat tour!).

Some other well-known libfixes include:

- ‑cation ‘a specific type of vacation’ ← vacation

- girlcation ‘vacation with girl friends’

- kidcation ‘vacation without kids’

- staycation ‘vacation at home’

- ‑copter ‘having a spinner rotor for flight’ ← helicopter

- gyrocopter

- quadcopter

- ‑dar ‘ability to perceive X’ ← radar

- gaydar

- humordar

- jewdar

- sarcasmdar

- ‑doodle ‘cross with a poodle’ ← labradoodle

- bernadoodle

- goldendoodle

- ‑erati ‘the elite within a group’ ← illuminati

- literati ‘the educated/literate elite’

- digerati ‘internet elite’

- glitterati ‘famous, wealthy, and attractive people’

- twitterati ‘Twitter elite’

- wokerati ‘extremely woke people’

- ‑flation ‘growth in X’ ← inflation

- tipflation ‘growth in the size of tips’

- shrinkflation ‘increase in the reduction of the size of goods’

- stagflation ‘increase in stagnation’ / ‘stagnation + inflation’

- ‑gasm ‘explosive or pleasurable experience’ ← orgasm

- braingasm ‘intense intellectual stimulation’

- eargasm ‘climax of musical excitement’

- foodgasm ‘intense enjoyment of a food’

- nerdgasm ‘intense excitement at nerdy things/topics’

- ‑iversary ‘yearly recognition of X’ OR ‘recognizing an event every X intervals’ ← anniversary

- blogiversary ‘anniversary of a blog’

- adoptiversary ‘anniversary of an adoption’

- weekiversary ‘weekly recognition of an event’

- monthiversary ‘monthly recognition of an event’

- ‑licious ‘appealing in reference to X’ ← delicious

- babelicious

- bubblelicious ‘appealing bubbles’ (gum, boba tea)

- bootylicious

- Fergalicious ‘the sexual appeal of music artist Fergie’

- ‑(ma)geddon ‘disastrous or cataclysmic event’ ← armaggedon

- carmaggedon ‘incredible amount of traffic; large pileup’

- snowmaggedon

- toemaggedon

- ‑nomics ‘pseudo-scientific; economic policy of X’ ← economics

- Freakonomics

- Reaganomics

- hope-a-nomics

- ‑preneur ‘type of entrepreneur’ ← entrepreneur

- kidpreneur

- mompreneur

- solopreneur

- ‑pocalypse ‘a catastrophic event relating to or caused by X’ ← apocalypse

- beepocalypse

- snowpocalypse

- ‑scape ‘environment of X’ ← landscape

- mindscape

- seascape

- soundscape

- ‑splain ‘explain condescendingly or to one who is more knowledgeable in an area’ ← explain

- ablesplain ‘to explain a disability-related topic without knowledge of it’

- goysplain ‘to explain a Judaism-related topic to a Jewish person’

- mansplain ‘to explain condescendingly to a female listener’

- whitesplain ‘to explain a race-related topic to a non-white person’

- ‑tainment ‘type of entertainment’ ← entertainment

- edutainment

- familytainment

- gastrotainment / eatertainment

- infotainment

- scientainment

- ‑tarian ‘one who eats X’ ← vegetarian

- flexitarian

- pescetarian

- pizzatarian

- ‑thon ‘event characterized by intense effort and/or long duration ← marathon

- boreathon

- hackathon

- excuseathon

- knitathon

- readathon

- telethon

- walkathon

- ‑Tok ‘TikTok subcommunity’ ← TikTok

- BookTok

- CleanTok

- DanceTok

- MusicTok

- PlantTok

- TechTok

- ‑ussy ‘resemblance to a vulva or vagina’ ← pussy

- bussy ‘boy pussy’ or ‘butt pussy’ (anus)

- thrussy ‘throat pussy’

- donutussy ‘donut hole’ (the physical hole)

- baristaussy ‘barista pussy’ (source)

- Swarthmore College linguistics professor Kirby Conrad explained the use of the ‑ussy libfix by saying, “So, if you’re a really dedicated coffee artist and you really put your whole baristaussy into this latte, I’m expecting some killer latte art.” Incidentally, this is also a great example of the ass camouflage construction at work, where the body part stands in metonymically for the entire person.

- ‑ussy was actually selected as the Word of the Year by the American Dialect Society for 2022.

- ‑verse ‘the community of X’ ← universe

- cryptoverse

- Twitterverse

- ‑zilla ‘biggest/baddest/meanest/nastiest of its type’ ← Godzilla

- dogzilla

- bridezilla

- momzilla

Technologies seem to be an especially fertile ground for libfixes (or blends in general) (O’Dell 2016):

- blog-based

- blogosphere

- bloggerati ‘the blogger elite’

- Twitter-based

- twitterati

- twittersphere

- twitterpated ‘making excessive use of Twitter to tell the world about the minutiae of one’s life’

- twittercide ‘deleting one’s Twitter account’

- twittercation ‘a break from using Twitter’

- twitterhoea ‘sending too many tweets in a short span of time’

- twisticuffs ‘strong disagreement between tweeters’

- twitterholic

Libfixes don’t have to be suffixes either; some are prefixes:

- alt‑ ‘outside the mainstream’ ← alternative

- altcoin

- alt-history

- alt-right

- alt-rock

- crypto‑ ‘related to cryptocurrency’ ← cryptography

- cryptobro

- cryptocoin

- cryptocurrency

- cryptoverse

- franken‑ ‘human-altered interference with nature’ ← Frankenstein

- frankenfood

- frankenplant

- frankenword

- heli‑ ‘type of helicopter’ ← helicopter

- helipad

- heliport

- helidrome

- hyper‑ ‘relating to hypertext’ ← hypertext

- hyperlink

- hypermedia

- petro‑ ‘relating to petroleum’ ← petroleum

- petrodollar

- petrochemical

- petrocurrency

- petrostate

All this is just a small sampling of libfixes. There are many many more. This sampling doesn’t include Covid- and pandemic-related terms (quarantini, quarantigue, maskne, maskulinity, maskhole, covidiot, moronovirus, Faucism, Magat, or Spanish pandejo ← pandemic + pendejo ‘asshole’ [Berry 2022]) because it would be too exhausting to catalog them all. Something about that time period—perhaps the fact that everyone was chronically online, but more likely because there were so many new concepts and experiences that needed naming—led to a shocking proliferation of new blends and libfixes.

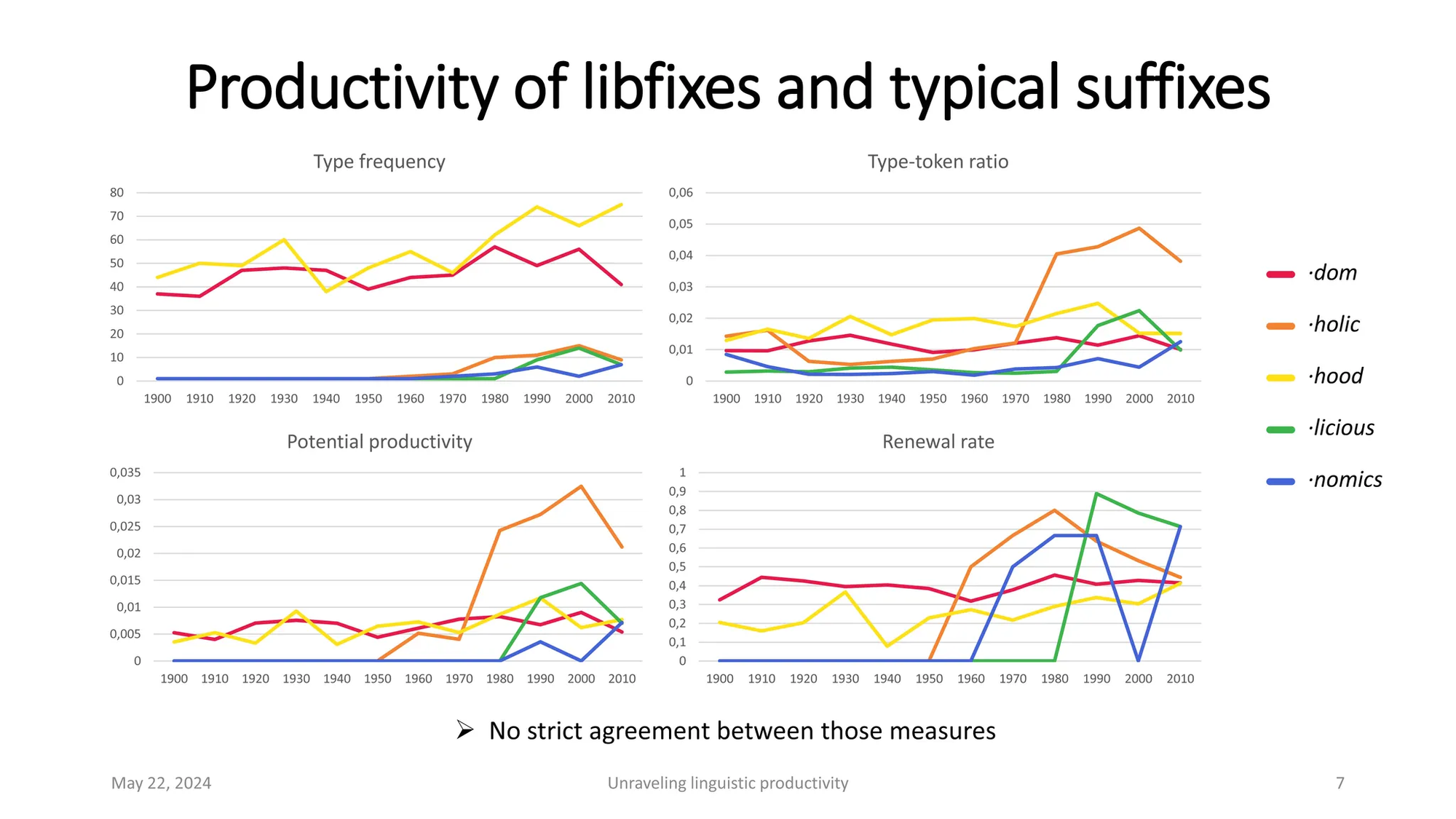

The big list of examples above notwithstanding, libfixation seems to be a relatively novel word-formation strategy, at least in English. By any measure of productivity (how readily a construction can be applied to new words or contexts), the most common English libfixes have become more productive over time. The charts below show a few different measures of productivity for the libfixes ‑holic, ‑licious, and ‑nomics, as well as the traditional suffixes ‑dom and ‑hood for comparison.

Given how closely libfixes are associated with the tech and internet spaces, their rise to prominence was probably spurred by the rise of computing and internet terminology, in much the same way that scientific terminology gave rise to an increase in acronyms and initialisms as a word-coinage strategy in the early 20th century. (Before the 1990s, acronyms and initialisms simply weren’t used to create new words. shit does not come from ship high in transit; news does not come from north-south-east-west; and so on. A good rule of thumb is: if someone tells you that a word was originally an acronym, no it wasn’t.)

Regardless, libfixes have now become so common that other languages in contact with English are starting to adopt the strategy for new words (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025). So let’s look at libfixes in other languages too.

Libfixes in languages other than English

I see the influence of English all the time in my language revitalization work. English speakers love to use noun compounding when coining words. This is unfortunate for language revitalization because most Native American languages are extremely verb-oriented: traditionally, nouns were derived from complex descriptive verbs whenever possible.

Of course, other languages have their own native libfixes. Just because English has influenced other languages in a way that makes libfixes more common doesn’t mean that libfixes weren’t already present in those languages. Some examples:

- Italian: ‑opoli ‘‑ville’, referring to a scandal ← Tangentopoli ‘Bribesville’ (Wikipedia: Libfix)

- Brazilian Portuguese: ‑ão ‘scandal’ ← Mensalão ‘Monthly payment–gate’ (Wikipedia: Libfix)

- Dutch (Hamans 2021)

- ‑talië ‘Italy’ (but used generically to mean ‘country’

- vertalen ‘interpret’ → Vertalië ‘country of interpreters’

- hospitaal ‘hospital’ → hospitalië ‘hospital as long-term residence’

- kapitaal ‘capital’ → Kapitalië ‘country where capital rules’

- betalen ‘pay’ → Betalië ‘country where one has to pay for everything’

- ‑talië ‘Italy’ (but used generically to mean ‘country’

- Romanian: ‑izdă ‘vulva’ (offensive/sarcastic) ← pizdă ‘vulva’ [slang] (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025)

- feminizdă ‘female feminist’ [offensive] ← feministă ‘female feminist’

- Merkelizdă ‘Merkel’ [offensive] ← (Angela) Merkel

- Spanish: pandejo ‘covidiot’ ← pandemic + pendejo ‘asshole’

It’s difficult to know, however, how much the origin of the Italian and Portuguese libfixes can be attributed to influence from English ‑gate, especially given that ‑gate is by far the most popular English libfix, and also the one most likely to appear in international news outlets because of its political nature. Perhaps those two libfixes should be considered calques (loan translations) rather than truly native constructions. I leave it to other linguists to sort that one out. (Anybody need a good thesis topic?)

The Romanian libfix, on the other hand, likely isn’t a calque of English ‑ussy, since ‑ussy is very recent and data on ‑izdă comes from a corpus spanning the last 15 years (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025). ‑izdă also only attaches to animate nouns, and refers derogatorily to the entire person rather than to a specific body part, unlike ‑ussy which may attach to inanimate nouns, refers specifically to the body part, and also (surprisingly) is typically used in a positive and playful manner rather than derogatorily.

Despite pizdă being a feminine noun, a few masculine versions of the libfix have been back-formed from the feminine ones too:

- ziarizd ‘male journalist’ [offensive] ← ziarizdă ‘female journalist’ [offensive] ← ziaristă ‘female journalist’

- minimalizd ‘male adept of minimalism’ [offensive]

Notably, no use of the feminine version, minimalizdă, has been documented, suggesting the emergence of an independent masculine version of the suffix.

Because scholarly awareness of libfixes is still so recent, there haven’t yet been good studies of them in other languages. There have however been a few studies which examine the influence of English libfixes on other languages. Other languages can outright borrow English libfixes and attach them to native words (with minor spelling changes and phonological adaptation), as shown in the examples below.

- Polish

Rywingate ‘political scandal caused by Lech Rywin’

teleholik ‘teleholic’

(Konieczna 2012) - Romanian

Băsescugate ‘scandal involving former Romanian president Băsescu’

SRIgate ‘scandal involving the SRI [Romanian intelligence service]’

romgate ‘scandal involving Rome’

curcubeoholic ‘addicted to rainbows’ ← curcubeu ‘rainbow’

ihtioholic ‘addicted to fish’ (literally ‘ichthyoholic) ← ihtio‑ ‘ichthyo‑’

călătoholic ‘addicted to traveling’ ← călători ‘to travel’

veveritzilla ‘huge squirrel’ ← veveriță ‘squirrel’

șnitzilla ‘huge schnitzel’ ← șnițel ‘schnitzel’

varaton ‘long vacation session during the summer’ ← vară ‘summer’

sarmaghedon ‘a meal where one eats too many meat rolls’ ← sarma ‘meat rolls’

pornaghedon ‘a sudden end to a politician’s career due to video recordings of him having sex’ ← porno ‘porn’

(Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025)

Italian has also borrowed ‑gate and ‑nomics, and Bulgarian has borrowed ‑holic (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 248).

As mentioned above, languages can also borrow entire word-formation strategies like libfixation without borrowing specific words or libfixes. One study documents the increased use of clipping (truncation/shortening of words) in Polish and noun-noun compounding in both French and Polish due to influence from English (Renner 2018). Another showed that Dutch libfixing has increased under influence from English (Hamans 2021), and a third showed that blends (defined below) have increased in Bulgarian, Italian, and Dutch (see Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 248 for sources). In Romanian, pervasive influence from English has led blending to become the default strategy for naming hybrid objects in younger generations. In one experiment, subjects were asked to name, using only a single word, some imaginary hybrid entities. Fully 68.31% of the words they created for these hybrid entities were blends, and only 12.22% were compounds, which was unexpected because compounding has been a major word-formation process in Romanian but blending was not (until recently). (Vasileanu, Niculescu-Gorpin & Radu-Bejenaru 2024)

I also see the influence of English word-formation processes all the time in my language revitalization work: Many Native American communities are working to revitalize their endangered languages, and part of this process involves coining new words for things and activities in the community. However, because these languages are endangered, many of the members within these communities speak English rather than their heritage language. And English speakers love to use noun compounding when coining words. This is unfortunate, because most Native American languages are extremely verb-oriented: traditionally, nouns were derived from complex descriptive verbs whenever possible.

As an example, the traditional Chitimacha word for ‘writing utensil’ (pen, pencil) is naakxtempuyna, which literally means ‘they habitually write with it’, from the verb naakxte‑ ‘write’ (literally ‘to paper’). Similarly, ‘bridge’ is pamtuyna ‘they habitually cross it’, from the verb pamte‑ ‘cross’. But when the Chitimacha tribe needed a word for ‘net’ (in sports), they chose to create the compound noun cii tuukun, literally ‘rope bag’ (ciq ‘rope’ + tuukun ‘bag’), rather than something like *dzehtuyna ‘they usually catch/trap with it’, from the verb dzeht‑ ‘to trap/catch …; to make a play in stickball’. Since I began working with the Chitimacha tribe in 2008, I have gently encouraged them to reach for verbs before nouns when coining new words. Nonetheless, years of English influence have resulted in a significantly higher proportion of compound nouns in the lexicon than traditional Chitimacha had. Shifts in grammatical tendencies like this are common in endangered languages (Palosaari & Campbell 2011).

In the second half of this series, we’ll explore the science behind libfixes: the sound patterns they follow, where they come from, how your brain processes them, and what they teach us about how language changes. If you haven’t subscribed already, be sure to do so to receive Part 2!

ℹ️ Articles in this Series

- Part 1: Libfixes: When word parts go rogue [this issue]

- Part 2: The science of libfixes: How libfixes work, where they come from, and what they teach us about language and the mind

📑 References

- Barnhart, Robert K. (ed.). 1988. Chambers dictionary of etymology. Chambers.

- Berry, Jack. 2022. Neologasming: Topics in Modern English word formation. Term paper.

- Delhem, Romain & Caroline Marty. 2024. Measuring the correlation of productivity rates for English libfixes. Presented at the Unraveling linguistic productivity: Insights into usage, processing and variability.

- Hamans, Camiel. 2021. A lesson for covidiots about some contact induced borrowing of American English morphological processes into Dutch. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia 56(s1). 659–691. https://doi.org/10.2478/stap-2021-0009.

- Konieczna, Ewa. 2012. Lexical blending in Polish: A result of the internationalisation of Slavic languages. In Vincent Renner, François Maniez & Pierre Arnaud (eds.), Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives on Lexical Blending (Trends in Linguistics: Studies & Monographs 252), 51–74. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110289572.51.

- O’Dell, Felicity. 2016. Creating new words: affixation in neologisms. ELT Journal 70(1). 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv054.

- Renner, Vincent. 2018. French and English lexical blends in contrast. Languages in Contrast 19(1). 27–47. https://doi.org/10.1075/lic.16020.ren.

- Vasileanu, Monica & Anabella-Gloria Niculescu-Gorpin. 2025. Romanian libfixes in the making. In Sabine Arndt-Lappe & Natalia Filatkina (eds.), Dynamics at the lexicon-syntax interface (Formulaic Language 6), 241–266. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111321905-009.

- Vasileanu, Monica, Anabella-Gloria Niculescu-Gorpin & Cristina-Andreea Radu-Bejenaru. 2024. Keep calm and carry on blending: Experimental insights into Romanian lexical blending. Word Structure 17(1–2). 56–90. https://doi.org/10.3366/word.2024.0236.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.