The science of libfixes

How libfixes work, where they come from, and what they teach us about language and the mind

A libfix (short for liberated affix) is a part of a word that has escaped its parent word and become a new affix, such as ‑core (cottagecore, Barbiecore, hopecore), ‑cation (staycation, girlcation, kidcation), or crypto‑ (cryptocurrency, cryptobro, cryptoverse). In the first part of this 2-part series, we explored the meandering history of the libfix ‑holic and saw tons of examples of libfixes from both English and other languages. In this second part, we’ll dig into the linguistic mechanisms that make libfixes tick—the subconscious sound rules you’re following when you use them, how they form in the first place, and how our brains process them—and what all this teaches us about how language works.

ℹ️ Articles in this Series

- Part 1: Libfixes: When word parts go rogue

- Part 2: The science of libfixes: How libfixes work, where they come from, and what they teach us about language and the mind [this issue]

Libfixes vs. blends

Like all newer technical terms, the exact definition of a libfix is still contentious, but we can nonetheless delineate the concept a bit more precisely.

First off, libfixes are more than just simple rebracketings. What do I mean by this? The English words apron, newt, and umpire were originally more like napron, ewt, and numpire, but the boundary between the indefinite article a/an and the word was reanalyzed in a process of rebracketing:

- a napron → an apron

- an ewte → a newt

- a noumpere → an umpire

A similar process happened with the Romanian adjectival suffix ‑os ‘abounding in …’. It was originally used like so:

- dealuri ‘hills’ → deluros ‘hilly’

- colțuri ‘corners’ → colțuros ‘edgy’

Speakers saw the sequence ‑uros frequently enough that they took it as the adjectival suffix, and now it can be used to form adjectives like buburos ‘pimply’ (bubă ‘pimple’ + ‑uros) (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 244).

Neither of the above sets of examples are considered libfixes. They merely adjust the boundaries of existing words/affixes rather than create new ones. While libfixes do always involve some type of “re”bracketing (more on this later), rebracketing alone isn’t what defines them.

Secondly, existing affixes used on new words with their original meaning intact also do not count as libfixes (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 244). For example, ‑cracy, from the Ancient Greek suffix ‑κρατία ‑kratía ‘rule, government’, has been used playfully/critically in recent years to form new words such as idiocracy, shopocracy, kakistocracy. Likewise, we now have rizzology to accompany older uses of ‑ology ‘the study of a particular subject’. But no new affix has been created in these cases.

However, libfixes do include cases of existing affixes that have undergone significant changes in meaning. For example, ‑verse is generally considered a libfix because it now refers to ‘community of X’ rather than its originally meaning ‘turned’ (uni‑verse etymologically meant ‘turned into one’). This is also the case for many of the prefixal libfixes listed above:

- cyber‑ (cybercensorship, cyberbully) counts as a libfix because it means ‘relating to the internet or computers generally’, and no longer has any connection to the original Greek κυβερνήτης kŭbernḗtēs ‘steersman’. cyber‑ is simply a blending of cybernetic.

- petro‑ (petrodollar, petrostate) counts as a libfix because it isn’t based on the original Latin or Greek roots petra or πέτρα pétra ‘stone, rock’, but instead comes blends involving petroleum.

- crypto‑ (cryptocoin, cryptoverse) counts as a libfix because it’s based on the term cryptocurrency and refers to the ‘currency’ part of its source word rather than ‘cryptography’ part.

This connection between libfixes and blends turns out to be key to their definition, as we’ll see in a bit.

The phonology of libfixes

It may be more useful to think of libfixes not so much as a new type of affix, but rather as a new template that can be used to create new blends.

The boundaries of libfixes are often fuzzy. Consider two different versions of the ‑geddon libfix: ‑geddon vs. ‑mageddon:

- ‑geddon: cybergeddon

- ‑mageddon: gaymaggedon

Or ‑holic vs. ‑aholic/‑oholic:

- sugarholic

- workaholic

The reason for this variation is that libfixes like to preserve the syllable structure and stress pattern (the prosody) of their original source word (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 246). For example, most (but not all) ‑tainment derivatives are 4-syllable words stressed on the penultimate (second-to-last) syllable, just like entertainment:

- e.du.ˈtain.ment

- in.fo.ˈtain.ment

- sci.en.ˈtain.ment

If any of the abbreviations or notations in this article are unfamiliar to you, check out the “How to read linguistics” page. It lists all the abbreviations, conventions, and notations used in Linguistic Discovery content.

In the case of ‑geddon, the speaker chooses whichever version of the libfix—‑geddon or ‑mageddon—best preserves the prosodic template of the original word armageddon. When ‑geddon attaches to a word with 2 or more syllables, the simple ‑geddon version suffices to fill out the template:

- cy.ber.ged.don

- ba.na.na.ged.don

But when ‑geddon attaches to a 1-syllable word, speakers recruit more material from the original armageddon to fill in the rest of the template, usually ‑mageddon but sometimes just ‑aggedon:

- car.ma.ged.don

- snow.ma.ged.don

- porn.a.ged.don

Another great example of this template-filling process is the word Whoniverse ‘all the fictional media related to the television program Dr. Who’. Almost always, the libfix ‑verse appears as ‑verse, but in this case it recruits the ‑ni‑ of universe as well, because the resulting derivation Whoniverse almost exactly matches the prosodic template of the original word, universe (just with an extra /h/ sound at the beginning).

Of course, sometimes the prosodic templates of the original word and the new base word match so closely that it’s impossible to tell where the boundary lies:

- Karmageddon (a 2011 movie) ← karma + ???

It is this preference for preserving the prosodic template of the source word that motivates the insertion of a dummy vowel (called an epenthetic vowel) in many libfixes:

- work‑a‑holic

- hack‑a‑thon

- crunch‑a‑licious

- blog‑o‑sphere

In fact, most libfixes are semantically transparent precisely because they preserve enough of the original word and its prosodic template that you know the original word being referred to. Some researchers actually include this in their definition of a libfix: “word parts emerging in blends that are analogically used in coining new words, while still preserving the connection with their source-words” (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 241). So even if you’ve never encountered the word snowmageddon—or the libfix ‑geddon in general—you can still guess its meaning because enough of the original word armageddon is preserved, either directly in its consonants and vowels, or indirectly in its overall prosodic profile.

Given this behavior, it may be more useful to think of libfixes not so much as a new type of affix, but rather as a new template that can be used to create new blends.

Lastly, let’s look at what happens to libfixes when there’s a mismatch between their spelling and their pronunciation. Take the libfix ‑splain as an example. It originates as a blend with the word explain, but it’s spelled ‑splain not ‑xplain. The reason for this is because the letter ⟨x⟩ in the Roman alphabet typically represents a sequence of two sounds /ks/, and the syllable boundary in explain just so happens to fall right between those two sounds—right in the middle of the ⟨x⟩, so to speak. If I were to write explain phonemically (according to its sounds rather than its spelling), it’d be /ɛk.spleᶦn/. The part of the word that became the libfix was only the second syllable, /spleᶦn/, so we write it as ‑splain.

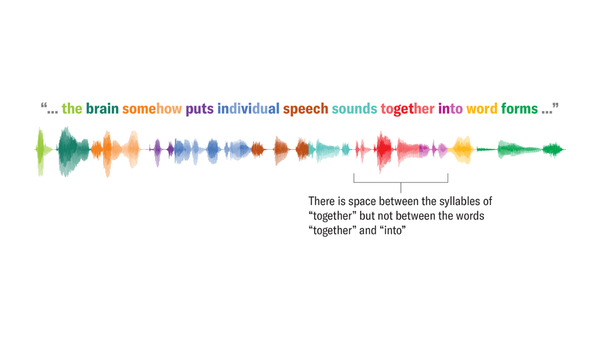

What all this demonstrates is that speakers create blends and libfixes based on their sounds rather than their spelling—and do so without even realizing it! In fact, all the phonological behaviors in this section illustrate just how much unconscious knowledge speakers have about sound patterns in their own language. We apply these moderately complex rules about prosodic profiles and syllable boundaries with no awareness that that’s what we’re doing, and I think that’s pretty remarkable.

Where do libfixes come from?

Libfixes are always based on an initial blend, not the words that originally made up the blend or their etymologies.

All libfixes start out as parts of a blend. A blend is a word formed by combining parts of existing words (Bauer 2004: 22). Canonical examples in English are smog (smoke + fog) and motel (motor + hotel). Blends were also famously called portmanteau words by Lewis Carroll, who coined the term to describe the words of the Jabberwocky poem in Through the Looking Glass (1871), like slithy (slimy + lithe) and mimsy (miserable + flimsy):

You see it’s like a portmanteau—there are two meanings packed up into one word.

~ Humpty Dumpty explaining words in the Jabberwocky poem to Alice.

In the English of the time, a portmanteau was a suitcase that opened into two equal sections, from the French porte‑manteau (porter ‘to carry’ + manteau ‘cloak’) (Etymonline: portmanteau). In this article, however, I’ll continue to refer to them as blends.

The chopped up bits of words that arise from blends are often called splinters. Every libfix starts out life as a splinter. Very occasionally, splinters can even transcend the affix stage and become fully independent words. This is what happened with burger: The word burger comes, of course, from hamburger, but the internal boundaries of that word were not originally ham‑burger. Instead the word is a reference to the city of Hamburg—a “Hamburger sandwich”, as it was originally called. But the presence of ham in that word motivated English speakers to reanalyze its internal boundaries as ham‑burger—a process called analogical reanalysis, etymological reinterpretation, or most commonly, folk etymology, where speakers reinterpret the internal pieces of a word to match other words or affixes they’re already familiar with. This reanalysis then made it possible to use hamburger in a number of blends: cheeseburger, veggieburger, fishburger, nothingburger, etc. The new libfix ‑burger was born.

In addition to its status as a libfix, burger also became an independent word. This happened early in the libfixation process: cheeseburger is first documented in 1938 (and is the earliest ‑burger blend I’m aware of), but burger appears by itself as an independent word just a year later (Etymonline: burger). Because of its early appearance, many linguists analyze burger as simply a clipping (shortening) of hamburger rather than a bona fide libfix.

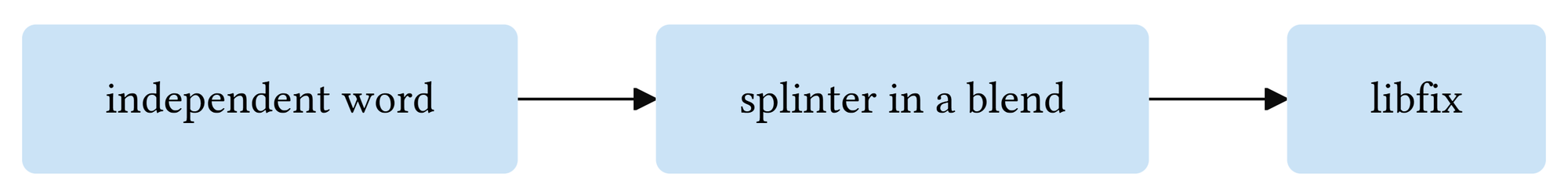

You should be starting to notice a pattern at this point: libfixes always follow the same diachronic (historical) trajectory (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 245):

- [optional] Speakers reanalyze an existing word as having different internal boundaries than it did historically (analogical reanalysis / etymological reinterpretation / folk etymology). This is what happened with the ‑burger of hamburger, and maybe the ‑copter of helicopter and the ‑ol of alcohol. This step isn’t necessary, but it can strengthen the perception of an internal boundary at the place where blending later happens (Step 2).

- Two words are blended (e.g. workaholic, cheeseburger, Brexit).

- The new blend becomes popular.

The popularity of the original blend serves as a template by which subsequent blends are formed: shopaholic, veggieburger, Grexit). The splinter from the original blend (‑holic, ‑burger, ‑exit) can now be reused with a variety of words.

The key point in all this is that libfixes are always based on an initial blend, not the words that originally made up the blend or their etymologies. chocoholic and twitterholic were formed by analogy to workaholic, not alcoholic. Tipflation and shrinkflation were formed by analogy to stagflation, not inflation.

This better explains why forms like crypto‑, cyber‑, and petro‑ count as libfixes but ones like ‑cracy and ‑ology don’t. Because every libfix is based on a blend and relies on that blend for its meaning, the original pieces of that blend and their etymologies are irrelevant. crypto‑ is based on cryptocurrency, not cryptography; cyber‑ is based on cybernetics, not the Greek κυβερνήτης kŭbernḗtēs ‘steersman’; ‑gate is based on Watergate, not the original word gate. By contrast, new uses of ‑cracy and ‑ology are always based the same original ‑κρατία ‑kratía and ‑λογῐ́ᾱ ‑logĭ́ā suffixes that they’ve always been.

The cognitive linguistics of libfixes

What all this teaches us about language is that we as language-users care more about patterns than structure per se.

From a cognitive perspective, it makes perfect sense that libfixes refer to the meaning of their source blend and not the meanings or etymologies of the parts of the source blend, because our brains don’t generally pay attention to the internal structure of words. You learn Watergate as a holistic unit, a single proper noun, not as two pieces, water + gate. When the libfix ‑gate hearkens back to the meaning of Watergate, that holistic meaning is the one that’s being referenced. Same with crypto‑: the libfix relies on the entire word cryptocurrency for its meaning, not its individual parts. And since the word cryptocurrency refers to a type of currency and not a type of cryptography, it is the currency meaning that gets highlighted every time crypto‑ forms a new word. A cryptocoin is any specific cryptocurrency; the cryptoverse is the world of cryptocurrency; a cryptobro is a bro who’s overzealous about cryptocurrency; and so on.

This also explains why the libfix ‑doodle exists as such rather than as *‑oodle. The blend that originally made the form popular was Labradoodle, whose splinters were Labrad‑ (< Labrador) and ‑oodle (< poodle). But it didn’t matter to speakers what the original splinters were, because speakers don’t pay attention to the internal structure of words! ‑doodle is based on an analogy to the entire word Labradoodle, not its parts. All that mattered was the prosodic profile of the whole word, Labradoodle. When speakers used Labradoodle as a template for other blends, it felt more natural to begin the libfix at the syllable boundary, as ‑doodle, than awkwardly in the middle of a syllable, as *‑oodle, even though *‑oodle was the original splinter. Labradoodle basically underwent rebracketing before spawning the libfix ‑doodle.

Even if our brains were capable of breaking down every word into its pieces every time we heard it (an implausibly cognitively demanding task), we simply don’t have the option. Unless you’re a lover of etymology (and even if you are), you probably aren’t aware of the historical meaning of the vast majority of words and their parts.

As a result, blends often give rise to libfixes that look exactly the same as a word or affix that was part of the original blend. But due to the libfixation process, these are now two totally distinct affixes! The Greek prefix crypto‑ is not the same entity as the libfix crypto‑; the English noun gate is not the same entity as the libfix ‑gate. They are splinters of blends that just so happen to have the exact same boundaries as the original parts of the blend.

This is what I meant earlier when I said that libfixes always involve “re”bracketing: two words are blended together in a way that creates a new word-internal boundary. Sometimes those new internal boundaries are different than they were before (helico‑pter → gyro‑copter, or al‑kuḥūl → work‑a‑holic), but sometimes they coincidentally happen to stay in the same spot (e.g. Water‑gate → nipple‑gate or crypto‑graphy → crypto‑currency). Nonetheless, a reanalysis always takes place.

What all this teaches us about language is that we as language-users care more about patterns than structure per se. Your brain doesn’t care where the internal boundaries of a word are—all it cares about is that ‑doodle has the same prosodic profile as poodle; hence bernadoodle instead of *berna‑oodle or *bernoodle. Your brain doesn’t care that ‑gate has nothing to do with actual gates, or that ‑aholic chops the word alcohol in two. Once it spots a pattern, it runs with it—even if that pattern is etymological nonsense.

Are libfixes just slang?

Neologisms like libfixes don’t violate or break the grammar of a language—they expand on it.

You probably noticed that the majority of libfixes convey a sense of either jocularity or pejoration (Gorman 2013)—basically a kind of wordplay or slang. Some scholars relegate libfixes to the margins of grammar or discount them entirely because of this (Vasileanu & Niculescu-Gorpin 2025: 241). These scholars view libfixes as mere acts of sporadic creativity rather than stable, rule-governed, productive affixes.

In reality, creativity and productivity sit on either end of a continuum. On the creative side of the continuum are the many, many, many nonce words (one-off creations or occasionalisms) coined for a specific context that never garner uptake outside that context. They are essentially wordplay. For example, it’s quite common for specific libfixes to be popular but still have none of their derivatives gain traction. ‑core and ‑ception are good examples of this: it’s easy to find one-off examples like momcore or dogception all over the internet because they were funny and made sense in the specific context they were used for, but outside that context they have no uptake. The libfix ‑ception comes from the name of the movie Inception, in which characters create alternate realities within a person’s mind, each reality embedded within the last. The ‑ception libfix now refers to any type of recursion like this. Thus the word dogception is incredibly useful for the TikTok video of a dog barking at a video of a dog barking at a video of a dog, but not a particularly helpful word otherwise. The vast majority of neologisms are like this: mere twinkles in the linguistic starscape—a brief flash and then they’re gone.

But occasionally conditions are propitious for broader adoption. If the new construction catches the right cultural wave, or maybe that playful one-off use becomes a viral TikTok, it can become ensconced within a particular linguistic community. One such use of the otherwise ephemeral ‑core libfix that seems to have reached this point is cottagecore, an internet aesthetic and subculture concerned with an idealized rural lifestyle. The word now has a stable meaning outside its individual contexts of use. Similarly, with sufficient repeated use, individual libfixes may even become extremely productive for the entire language community, like ‑holic, ‑gate, and ‑licious have.

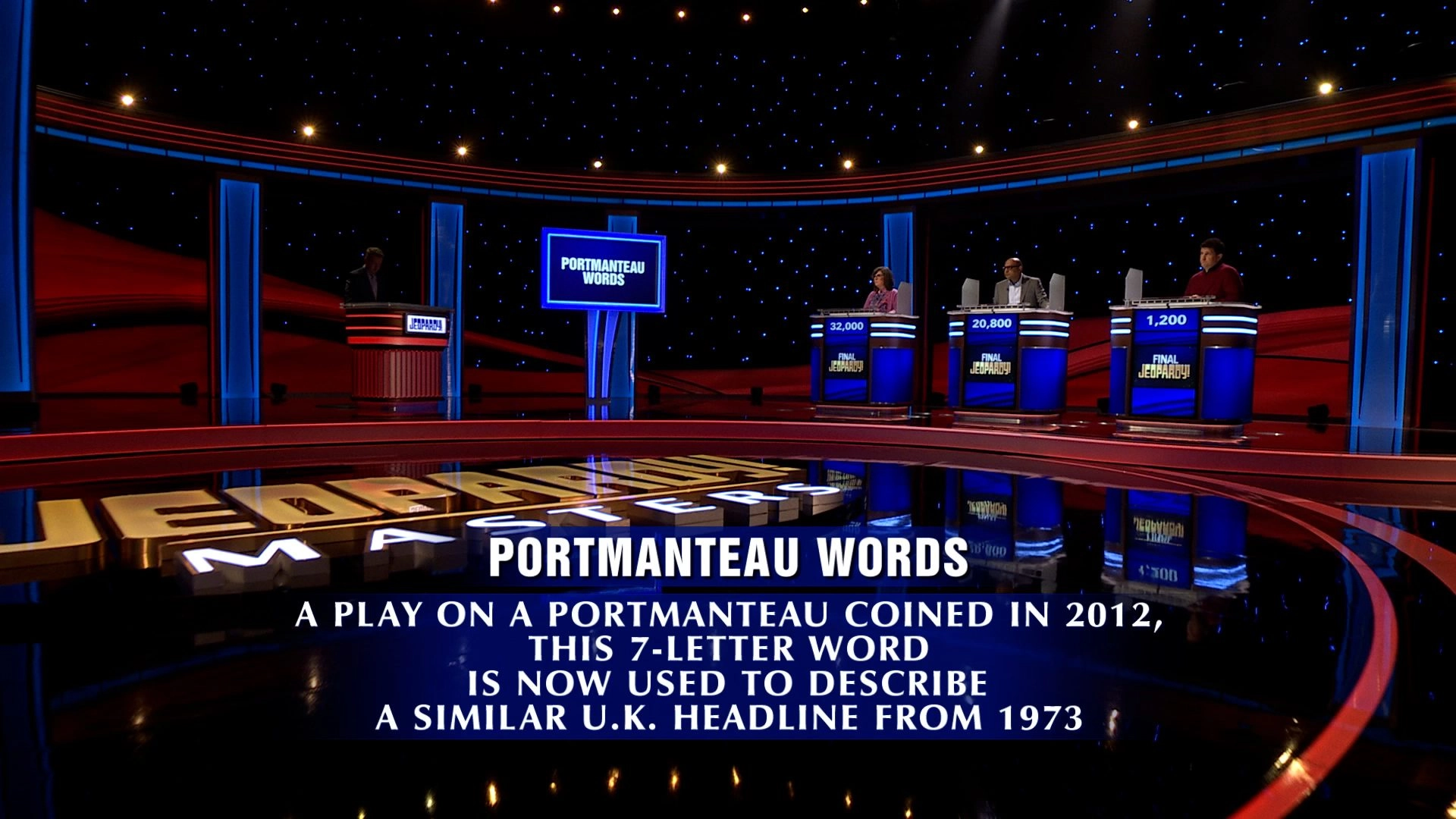

The single best example of this is probably ‑exit, which began life in the blend Brexit (British + exit), referring to the withdrawal of the United Kingdom (UK) from the European Union (EU). It first appeared in a blog post from 2012, where it seemed to be little more than witty word play. But the topic was so widely discussed, and term so widely adopted, that it swiftly spawned numerous derivatives, such as terms referring to other countries leaving the EU:

- Frexit (France)

- Grexit (Greece)

- Itexit (Italy)

- Spexit (Spain)

And the possibility of Scotland leaving the UK in response to Brexit:

- Scexit (Scottish exit)

And then the possibility of US states seceding:

- Calexit (California)

- Texit (Texas)

And then use in popular media:

Finally, the blend Brexit itself started to be used in other blends! Blends of blends!

- regrexit ‘regret over Brexit’

- Lexit ‘left-wing supporter of Brexit’

And not just the ending, but the beginning of Brexit was coopted for blends as well:

- Braccident

- Breferendum

- Bregret

- Bremain

- Bremorse

- Brextension

- Brexistential crisis

- Brexpert

- in-Bretween

- Brentry

We know these are blends of blends because, unlike the original libfix ‑exit which meant ‘end association with X’, these mean ‘X in relation to Brexit’. This is the meaning you’d expect from blending Brexit: regrexit means ‘regret about Brexit’ because it’s a blend of regret + Brexit rather than regret + ‑exit; Brexpert means ‘expert on Brexit’ because it’s a blend of Brexit + expert rather than British + expert.

This reblending is really surprising (and cool) because blended blends are naturally quite confusing, especially in this case since the boundaries between the splinters are exactly the same in the first blend and the reblend. In any case, its reblendability is a beautiful illustration of just how deeply ensconced Brexit has become in the British lexicon—a “real” word if ever there was one. Fittingly, the Collins English Dictionary selected Brexit as the word of the year for 2016. Brexit thus makes for a great illustration of how a new expression can go from a playful one-time creation to a stable term with a predictable meaning in relatively short order, sliding all the way from one end of the creativity ↔ productivity scale to the other.

This process of graduating from creative → productive has as its keystone one crucial fact: speakers would not take up a new expression if it didn’t utilize existing words and rules of the language in the first place. Neologisms like libfixes don’t violate or break the grammar of a language—they expand on it. Libfixes work precisely because existing popular blends provide them with lots of affordances: a speaker hears chocoholic for the first time and can (unconsciously) rely on workaholic and shopaholic and the general principles of how libfixes work to figure out that it means ‘person addicted to chocolate’. Far from being “mere slang”, libfixes are in fact illustrative of one of the most foundational processes by which language—and the human mind in general—operates: analogy. And in my opinion, they demonstrate that we humans are pretty damn good at it.

I hope this article has given you lots of good affixana to share with your acquaintances. I encourage you to share your favorite libfix from this article and tag me on social media! Thanks for joining me in this deep-dive into the linguaverse!

🙏 Credits

This issue of the Linguistic Discovery newsletter was edited by Amy Treber. If you’re looking for professional copyediting services, email Amy at amytreberedits@gmail.com.

The final responsibility for any mistakes or omissions is of course still wholly my own.

📑 References

- Bauer, Laurie. 2004. A glossary of morphology. Georgetown University Press.

- Gorman, Kyle. 2013. Defining libfixes. Wellformedness. https://www.wellformedness.com/blog/defining-libfixes/. (20 January, 2026).

- Vasileanu, Monica & Anabella-Gloria Niculescu-Gorpin. 2025. Romanian libfixes in the making. In Sabine Arndt-Lappe & Natalia Filatkina (eds.), Dynamics at the lexicon-syntax interface (Formulaic Language 6), 241–266. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111321905-009.

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my Amazon storefront here.

Check out my Bookshop storefront here.