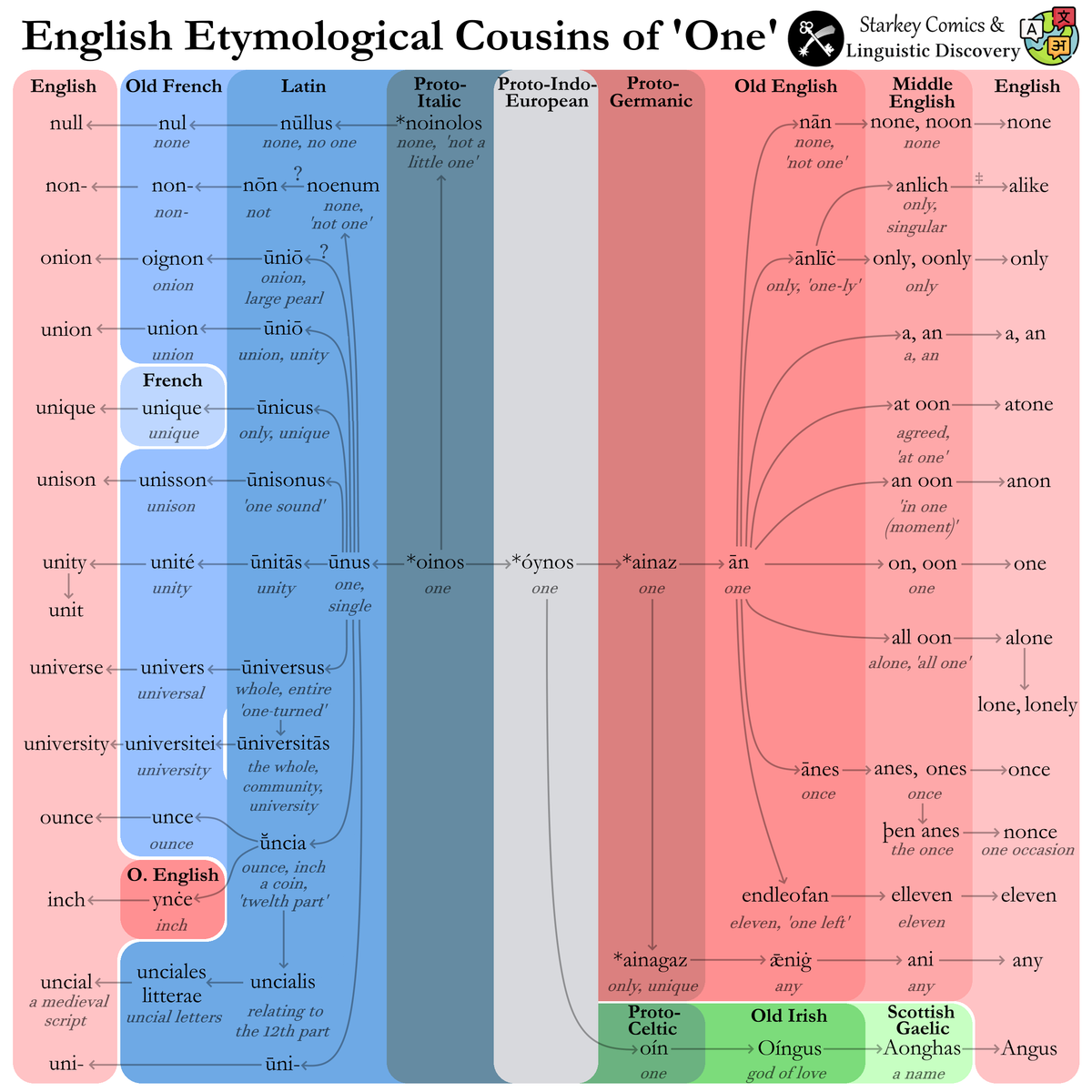

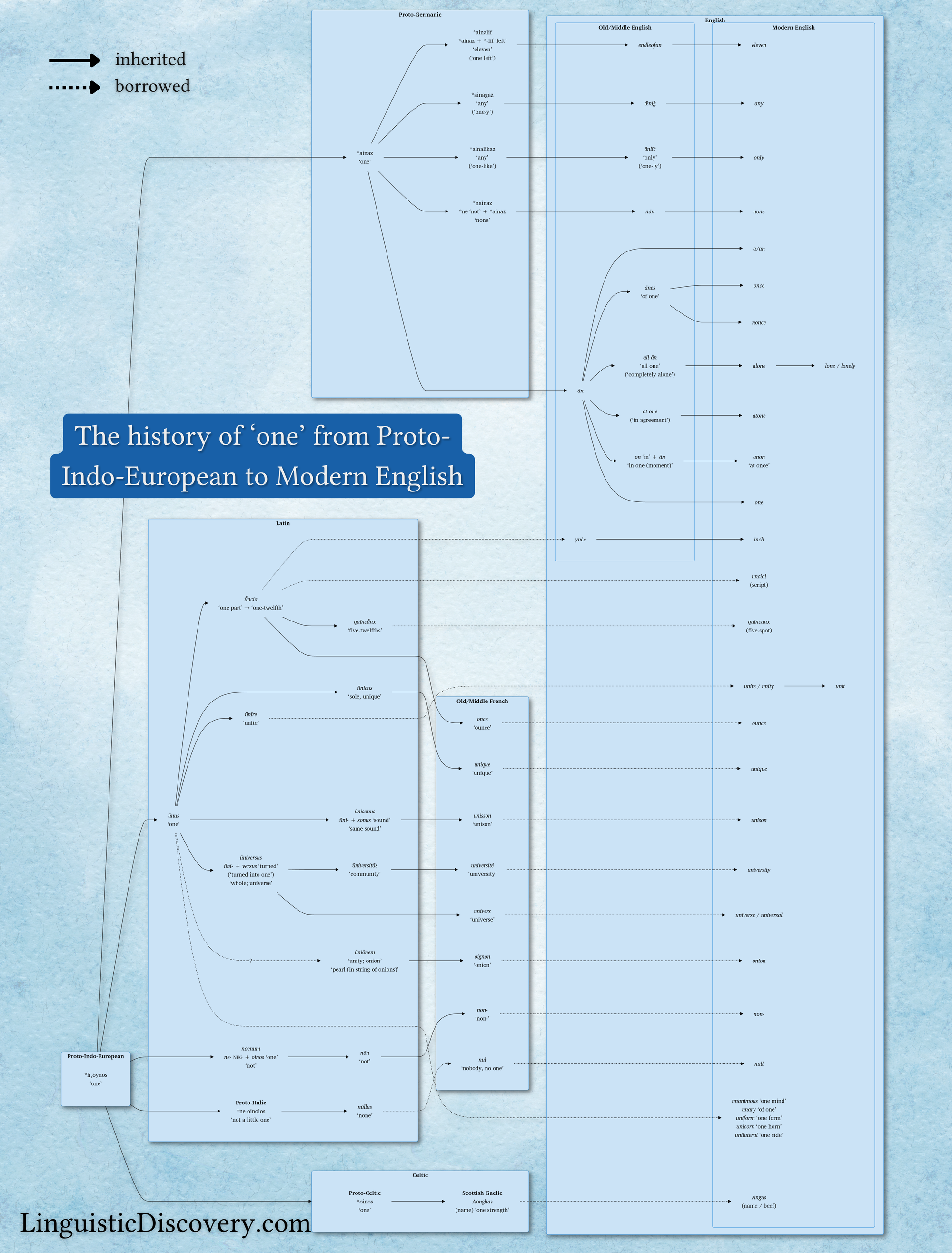

The etymology of ‘one’: From Proto-Indo-European to Modern English

There are over thirty English words that derive from the Proto-Indo-European word for ‘one’. This is the story of how they came to be, and what that story teaches us about how language works.

Today I’m going to take you on an etymological journey through the manifold histories of the word for ‘one’ from Proto-Indo-European 6,000 years ago to all the subtle ways that root is hidden in English today.

Put on your etymological adventure hat and/or grab yourself a drink and settle in, because we’ve got a 6,000-year journey ahead of us. ⏳🗺️

Prefer to watch or listen to this article instead? Here’s a video version:

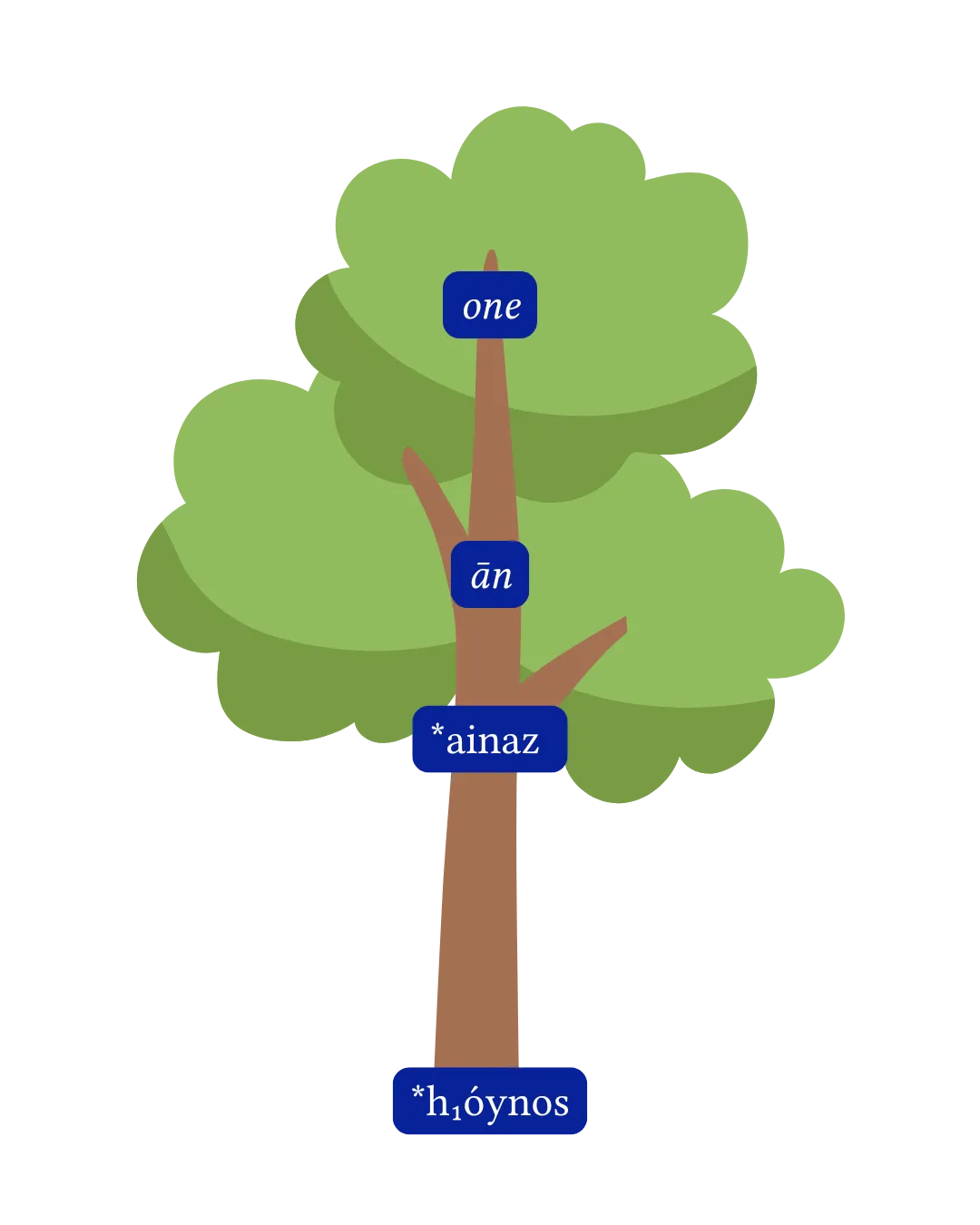

The Etymological Tree Trunk

The reconstructed word for ‘one’ in Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is *h₁óynos, and the most direct descendant of that word in Modern English is, unsurprisingly, one:

But while one and once took on the initial /w/, other words based on one didn’t. That’s why alone, atone, and only (which are all related to one, as we’ll see in a bit) aren’t pronounced with a /w/.

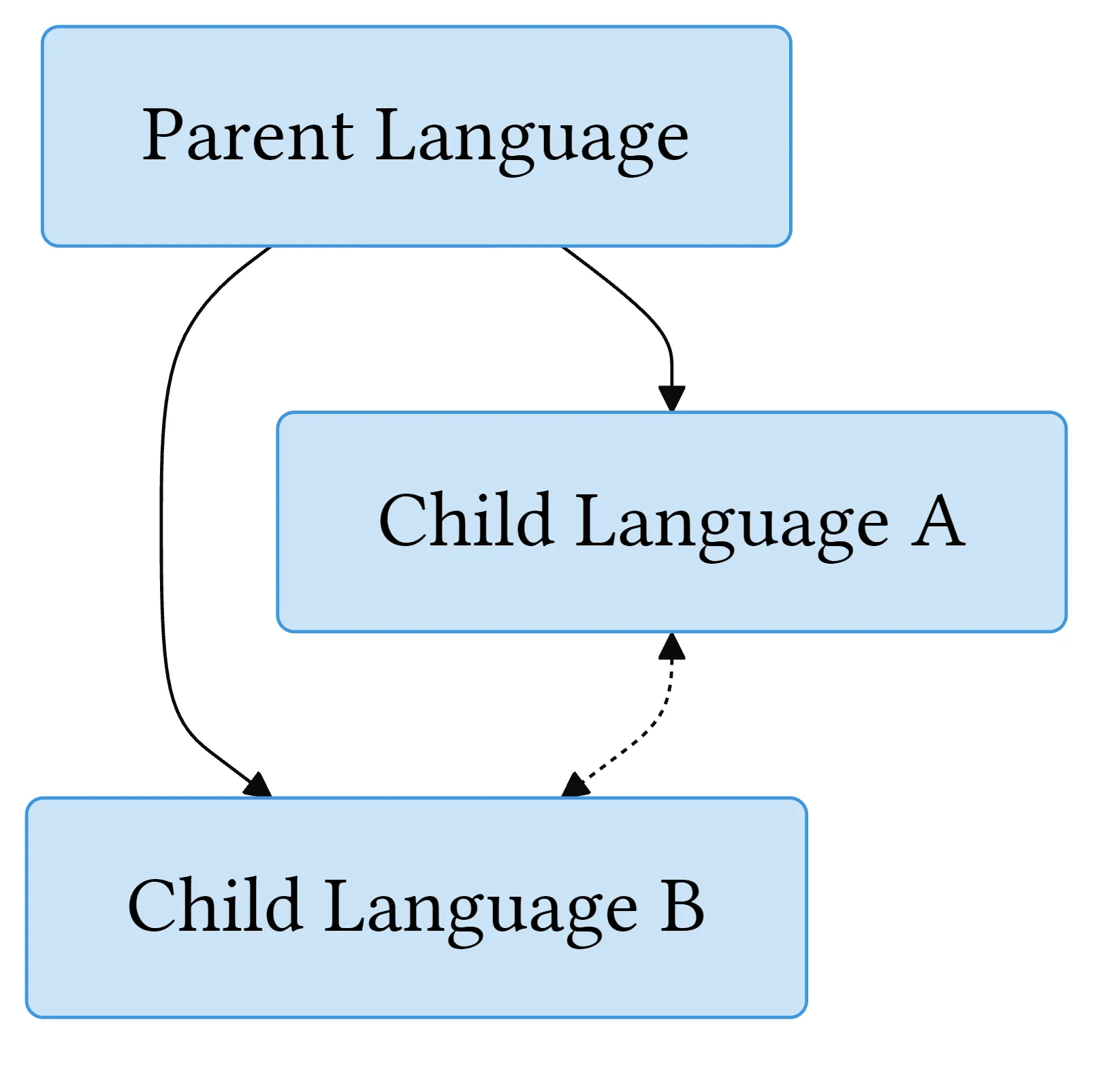

For the purpose of this article, think of this etymology as the main trunk of our etymological tree. All the other reflexes (descendants) of *h₁óynos will branch off from different parts of this trunk—some more recently in history, up near the very top of the tree, and some very early in the history of Indo-European, near the base of the tree. We’ll work our way from the top of the tree (more recent branchings) on down (older branchings).

Of course, in Modern English, one functions as more than just a number. It can also be used as an indefinite pronoun in expressions like “one would think”. This usage came about under influence from French on ‘somebody, someone’ and Latin homō ‘human being, person’. This is our first tiny leaflet off the main branch—two distinct senses of one in English. One of them is a content word with a concrete meaning, the other is a function word with an abstract grammatical meaning.

You can read more about the comparative method in this issue of the Linguistic Discovery digest.

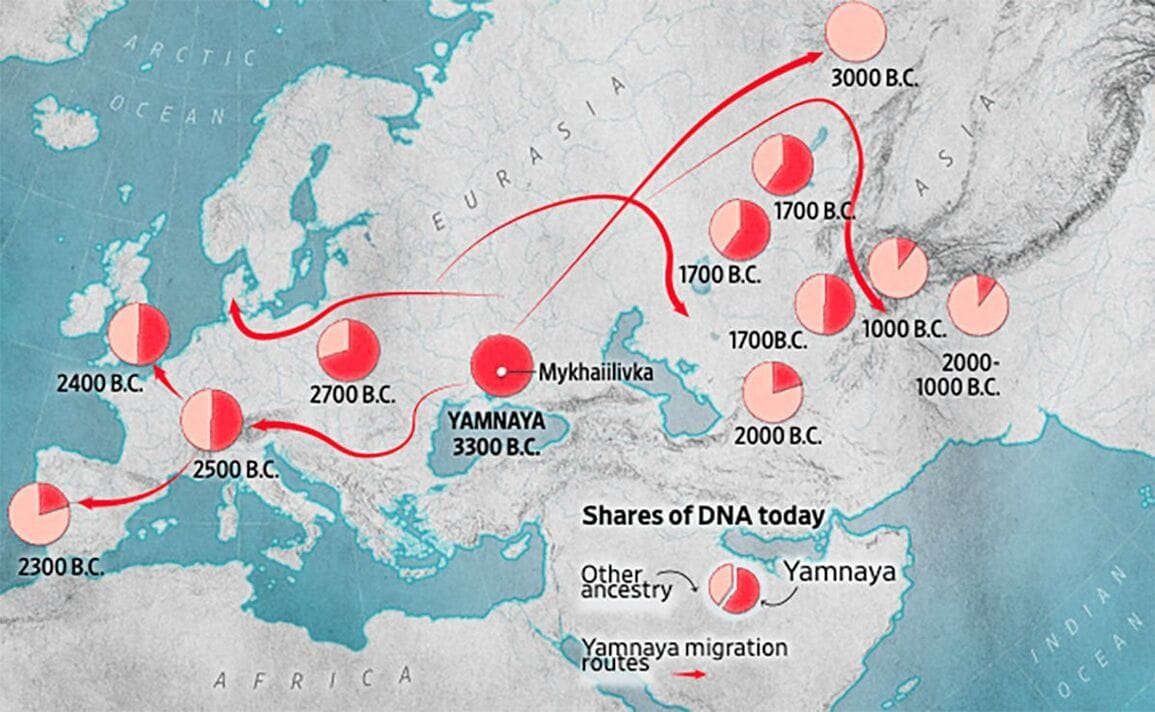

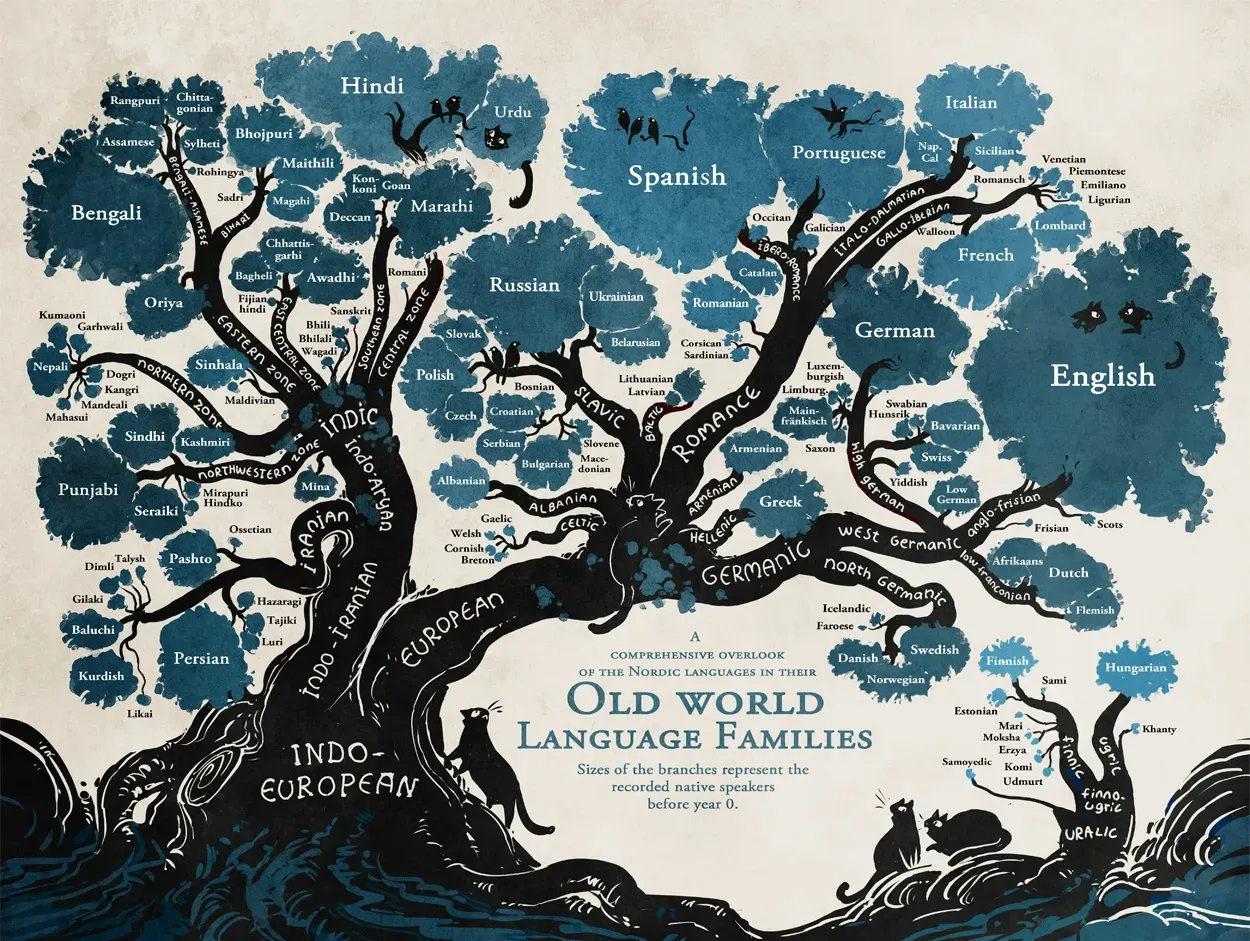

If an entire parent language has little or no extant written texts and has been reconstructed using these techniques, it has the prefix “Proto-”. Proto-Indo-European is the reconstructed parent language of all the modern Indo-European languages, while Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed parent language of all the modern Germanic languages (and is itself a child language descended from Proto-Indo-European).

Scholars believe that Proto-Indo-European had three distinct “laryngeal” consonants, but are uncertain as to exactly how these consonants were pronounced, so linguists write them as ⟨*h₁ *h₂ *h₃⟩. I put “laryngeal” in quotation marks because of that uncertainty. All we know is that *h₁ was an obstruent, *h₂ was likely a voiceless fricative pronounced in the far back of the mouth, and *h₃ had lip rounding (Ringe 2006: 8–9). One hypothesis is that *h₁ = [h], *h₂ = [χ], and *h₃ = [ɣʷ].

The acute accent indicates a pitch accent on that syllable, similar to stressed syllables in English, but without accompanying increases in loudness or length. The only difference on a pitch-accented syllable is a higher pitch.

Not used here are the palatal consonants *ḱ, *ǵ, *ǵʰ, whose exact pronunciation is also uncertain. All other characters in the Proto-Indo-European orthography are used in line with their standard meanings in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA).

Old English

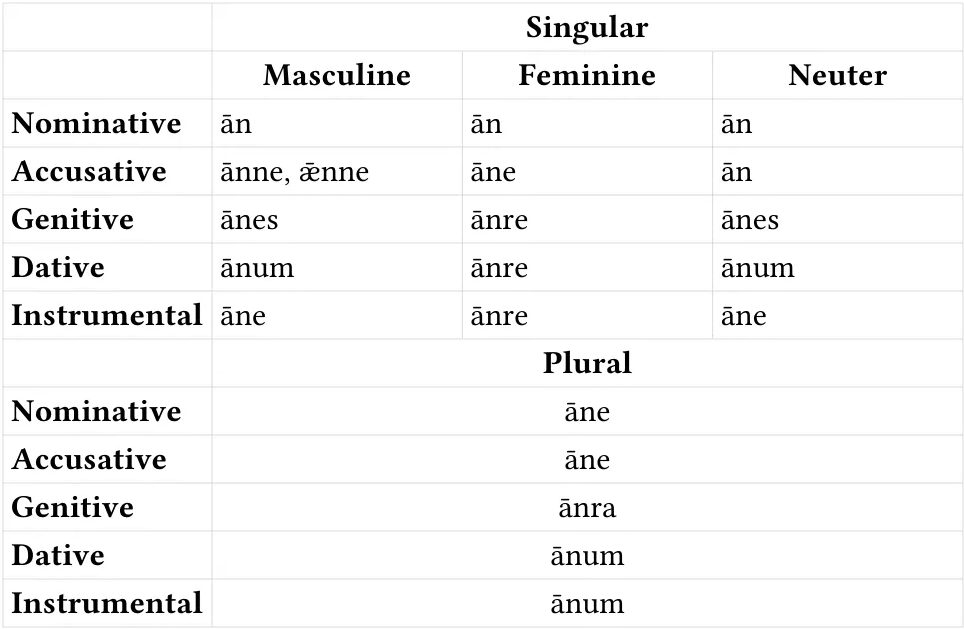

Now that we have the main trunk of our tree, let’s first explore the Old English branch, which itself sits on the older Germanic branch. The Old English word ān ‘one’ was used so frequently in several common phrases that the words in those phrases merged into a single new word (a process called univerbation):

- The phrase all ān ‘all one’, metaphorically meaning ‘entirely one’ or ‘completely alone’, became the Modern English word alone. The word alone in turn was shortened to lone, which later developed the adverb form lonely.

- The phrase æt ān ‘at one’ metaphorically meant ‘in agreement, in accord’, and that phrase became the Modern English word atone. Its meaning developed from ‘in accord’ to ‘make reparations for’, because making reparations for an action is one way to be in accord with someone.

- The phrase on ān meant ‘in one (moment)’ (on meant both ‘on’ and ‘in’ in Old English), and this became the Modern English word anon ‘in a short time; soon’, as in “more on that anon”.

Old English nouns were also inflected with various suffixes indicating their role in the sentence (case markers). The genitive (possessive) form of ān was ānes ‘of one’, with the genitive -es suffix. After a few pronunciation changes, that led to the Modern English word once. And if you remember in my earlier aside about the pronunciation of one, only the word one itself gained an initial /w/ in its pronunciation; the other words based on one didn’t. Well, since ānes was originally just the genitive form of ān, it too gained that initial /w/, which is why once is pronounced /wʌns/.

Before those sound changes occurred, however, ānes appeared frequently in the phrase to/for þen ānes ‘to/for the once’, meaning ‘the one occasion or instance’. The word þen was the precursor to Modern English the. Specifically, it was the dative form (indicating the recipient or beneficiary). But many speakers heard the /n/ in þen as belonging to the word ānes instead of þen, so the phrase became for þe nānes—a classic case of rebracketing or morphological reanalysis. The word nānes then came down to us in Modern English as the word nonce, meaning ‘occurring or used only once’, a term common in programming for single-use cryptographic keys.

That’s not the only time ān was involved in rebracketing, either. It became so common for ān to function as an indefinite pronoun meaning ‘someone’ that it became the indefinite article a/an! Today both words (one and a/an) exist side by side in English, but with different functions. There was so much variation in whether the /n/ of ān was perceived as part of ān or part of a following vowel-initial word that eventually the pattern generalized: today, a is used before words that start with a consonant sound, and an is used before words that start with a vowel sound.

Germanic

Now let’s climb down our etymological tree a bit from the Old English branch to the next closest one, Germanic. Germanic is one of the major branches of the Indo-European language family, along with Celtic (which includes Irish), Italic (which includes Latin and its descendant Romance languages, Spanish, French, etc.), Indo-Iranian (which includes Sanskrit), and several others. This is beautifully illustrated by Finnish artist Minna Sundberg in a 2014 installment of her web comic Stand Still, Stay Silent (below).

By the time Proto-Germanic branched off from the rest of the Indo-European languages, the Proto-Indo-European word *h₁óynos had become *ainaz in that branch of the tree. In addition to the Old English word ān ‘one’, *ainaz yielded a couple other words:

First, it took the adjective suffix *-gaz, which is the origin of the Modern English -y suffix. This Proto-Germanic word *ainagaz meant ‘only, singular, unique’. It became the Old English word ǣniġ ‘any’, then finally Modern English any—etymologically, ‘one-y’.

*ainaz could also take the suffix *-līkaz ‘-like’, becoming ainalīkaz ‘one-like’. (-līkaz is related to the Modern English word like and is also the origin of the -ly suffix.) In Old English this became ānlīċ ‘one-ly’, yielding Modern English only:

*ainaz could also be negated as *ne ainaz ‘not one’, which later merged as *nainaz ‘none’. (Univerbation again.) *nainaz became Old English nān, which in turn became Modern English none.

Now we come to the last etymology from the Germanic branch of the tree, which will finally explain the great mystery of why English uses the special words eleven and twelve for those numbers instead of *oneteen and *twoteen:

There is decent evidence to suggest that early Germanic had, if not a full-fledged base-12 (duodecimal) counting system, at the very least influences from such a system. That is, early Germanic speakers seem to have counted by 12s rather than 10s.

One piece of evidence for base-12 counting in early Germanic is that Old Norse used a mixed decimal-duodecimal counting system. The Old Norse word hundrað meant ‘120’ (twelve groups of ten instead of ten groups of ten). This influenced English usage as well: the English word hundred could still be used to mean ‘120’ until the 1400s.

A second piece of evidence is that in the earliest texts written in Germanic languages (such as the Gothic Bible), there are notes in the margins explaining to readers that certain numbers should be read “tenty-wise”, or in the base-10 counting system. These notes wouldn’t be necessary in a society that already consistently counted by tens.

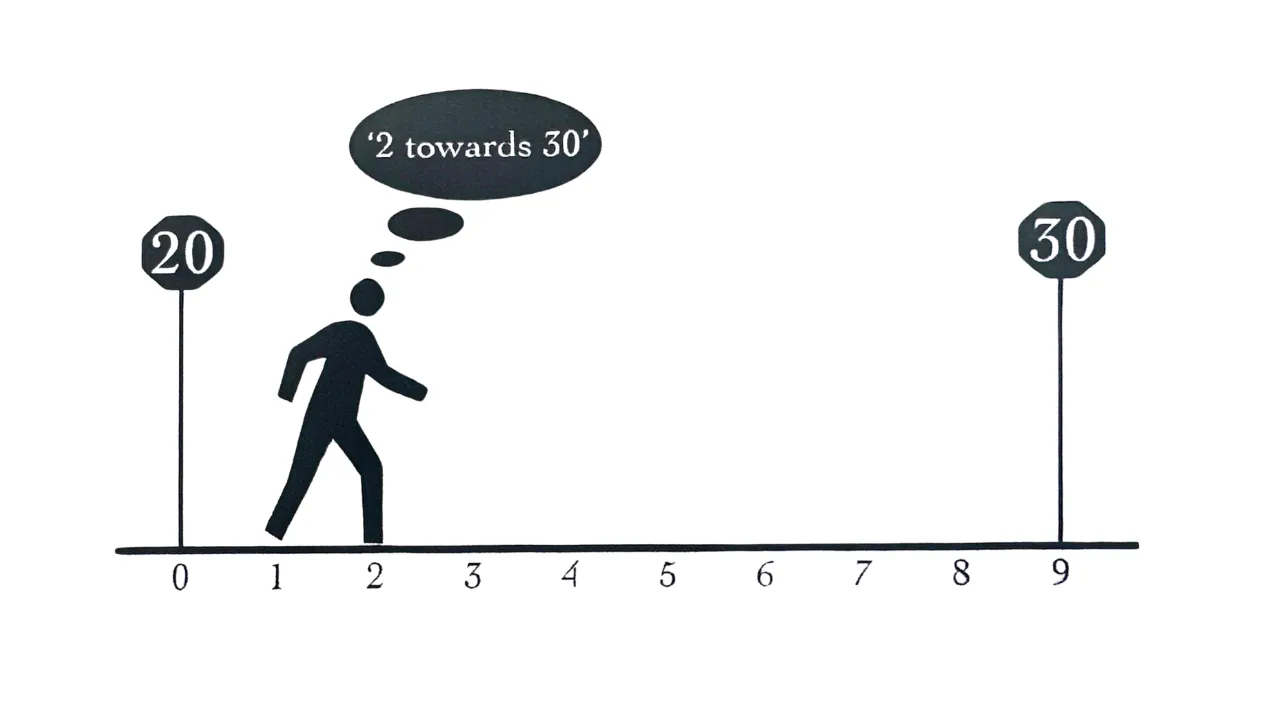

A final piece of evidence that the early Germanic peoples counted by twelves comes from the words for ‘eleven’ and ‘twelve’ themselves: in Proto-Germanic, these words were *ainalif ‘one left’ and *twalif ‘two left’, in the sense of ‘one left over (after ten)’ and ‘two left over (after ten)’. This style of counting past the base is called overcounting, and it is documented in other languages as well. For example, Old Turkic would express ‘twenty-seven’ as ‘seven thirty’, meaning ‘seven towards thirty’ (Harrison 2007: 183–184). It’s perfectly natural to say things like “we’re two over” in the context of numerical limits. You might say this if there are more people than chairs available, for example. Now imagine if this way of conceptualizing numbers were the only way to express ‘eleven’ and ‘twelve’, and you have their origin.

The reason the overcounting stops at 12 seems to be that early duodecimal influence. *ainalif became endleofan in Old English, and that developed into the Modern English word eleven, while *twalif eventually became twelve.

Now that we’ve perused the Germanic descendants of the Proto-Indo-European word for ‘one’, let’s turn to some other branches of the Indo-European family tree and the words from those branches that have wandered into English.

Romance

I use the word “wander” intentionally, because all the words in this and the following sections were not inherited by English from Proto-Germanic, its parent language. Instead, all these words were borrowed by various routes into English at different points in the language’s history—sometimes extremely early in its history, sometimes more recently.

Two historical events in particular inundated English with words of Romance origin: the Norman invasion of England in 1066, and the Renaissance. The Normans brought the French language with them into England, where it quickly became the language of the ruling class, marking the end of the Old English period and the transition into Middle English. English itself went practically unwritten from that point until the late 1300s. French is a Romance language (meaning it’s a descendant of Latin), so nearly all the vocabulary that English borrowed from French is ultimately of Latin origin. It’s also important to remember that many of these borrowings happened during the period of Old or Middle French, before many words had taken on the pronunciations and spellings that they have in Modern French. So, if a French word in this article looks strange to you, that’s why. During the Renaissance, on the other hand, scholars borrowed many words directly from Latin. French was no longer the intermediary for Latin borrowings.

Let’s explore those words that came from Latin by way of French first. The Proto-Indo-European word *h₁óynos became ūnus ‘one’ in Latin, and this formed a part of numerous other words in Latin. French then inherited those words before foisting them upon English.

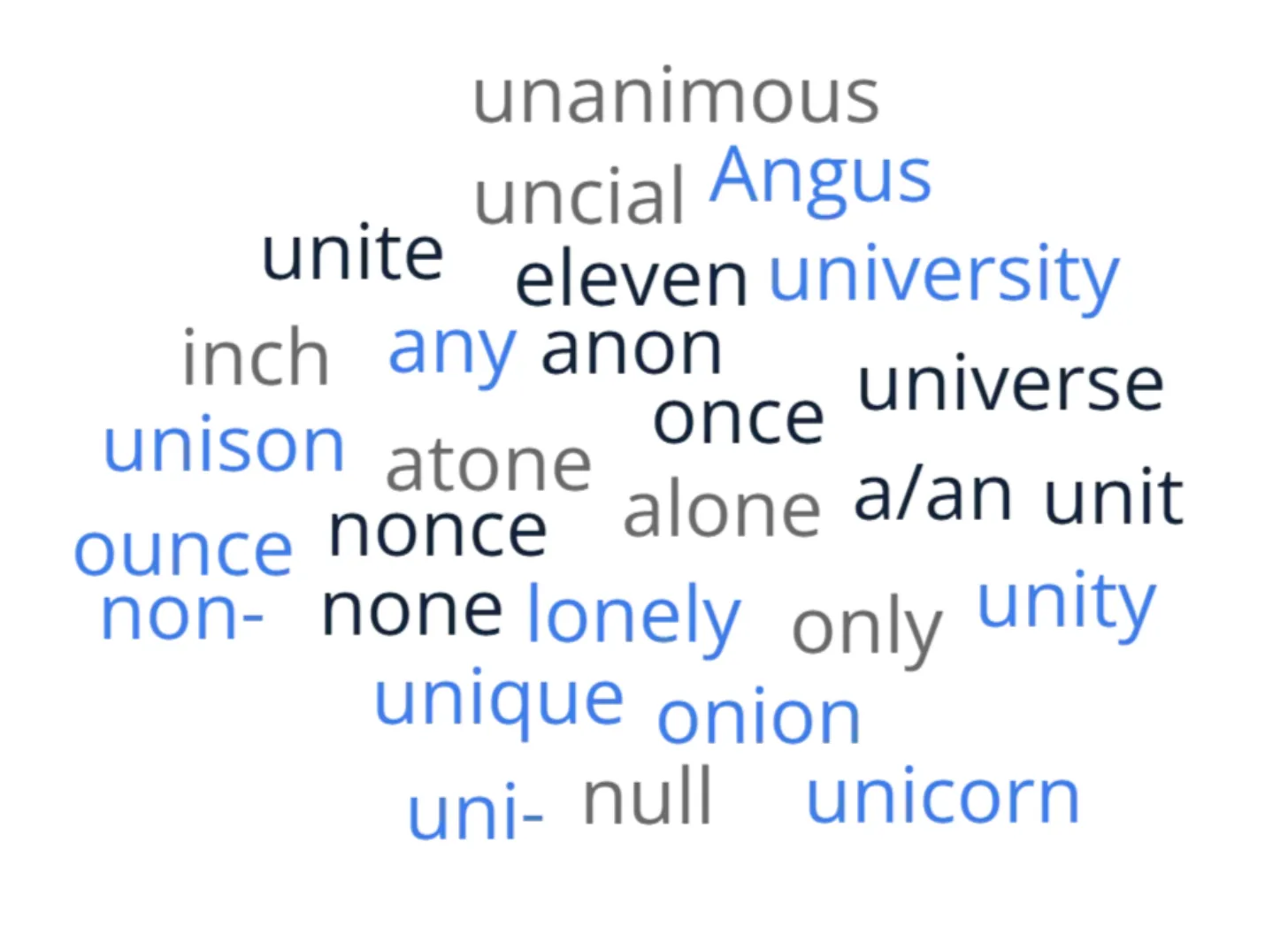

The most boring straightforward word is Latin ūnicus ‘sole, unique’ (literally ‘one-y’), which became French unique (English unique):

Latin ūnisonus ‘same sound’ (ūni- ‘one’ + sonus ‘sound’) became French unisson (English unison):

Latin ūniversus ‘whole; universe’ (ūni- ‘one’ + versus ‘turned’, meaning literally ‘turned into one’) became French univers (English universe).

ūniversus also had an abstract noun form, ūniversitās, which meant ‘community’ (an extension from the sense of ‘the whole (community)’). This later came to refer to an academic community specifically, yielding first the French universitei and then the English university.

A fun etymology is Latin ūniōnem ‘onion’, referring to the unity of an onion’s layers. It could also be used metaphorically to mean ‘pearl’ (because onions were sold in a string, so a pearl necklace was like onions on a string). Latin ūniōnem became Old French oignon and came into English as onion.

Now, remember how I said that some words entered English earlier than others? Well, sometimes the same word came into English twice (or more!)—once early in the language’s history and once later—yielding two different words in Modern English. When two words in the same language share a common historical source, they are called an etymological doublet (or triplet, and so on). A few quick examples are host and guest, ward and guard, and pipe and fife. Each of those pairs of words have the same origin.

This is what happened with the Latin word ū̆ncia ‘one part’ or ‘unit’. (The initial ⟨ū̆⟩ has both a breve and a macron because it’s unknown whether that vowel was long or short.) In actual use, this word actually meant ‘a twelfth part of something’ rather than a single part, because Romans divided many types of goods into units of twelve, such as the pound and the foot. Middle French inherited this word as once, at which point English borrowed it as ounce. Today an ounce is ⅟₁₆ of a pound rather than ⅟₁₂ of a pound because at one point the standard for what constitutes a pound changed.

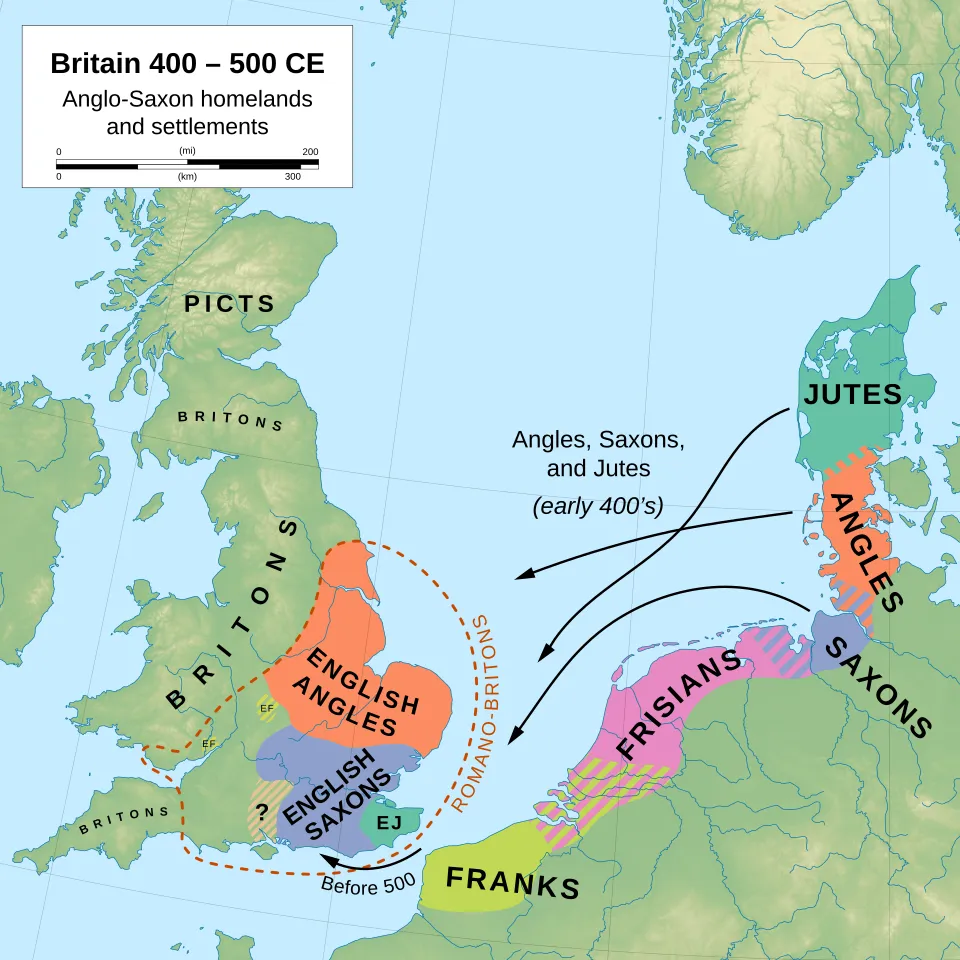

But that was merely the later borrowing. A millennium prior to that, before Old English even existed, the Germanic tribes of northern Europe were trading with, fighting against, and sometimes even fighting for, the Romans. As you might expect, those Germanic peoples borrowed many words for items they bought from the Romans, as well as some of their units of measure. One of those was the ū̆ncia.

Later, between the 5th and 7th centuries, some of those Germanic peoples would settle in Britain, mixing their West Germanic dialects into what would eventually become Old English. One of the words they brought with them was ynċe ‘inch’, which first appears in the Laws of Æthelberht, dated to the early 600s; that gives us the modern word inch.

While I don’t typically include technical or specialist jargon in these etymological surveys, I’ll impishly include two here because they’re fun:

Remember how I said a word can also be borrowed more than twice? You guessed it: ū̆ncia was also borrowed into English around 1650 as the word uncial, referring to a particular type of majuscule script (written entirely in capital letters) used from the 4th to 8th centuries. It was called uncial because the letters were “inch-high”, i.e., big.

Lastly, ū̆ncia also appeared in the Latin compound noun quīncū̆nx ‘five-twelfths’ (combining quīnque ‘five’ + ū̆ncia), which referred to a specific coin issued by the Roman Republic c. 211–200 BCE. However, that noun was later borrowed into English and soon came to refer to the specific arrangement of five units as seen on dice, with four units in the corners and one in the center, like so: ⁙.

There are two other reflexes of *h₁óynos that come to English through French, but not by way of Latin ūnus. In Old Latin (the period from the earliest written Latin inscriptions up until the Classical period, c. 600s – 75 BCE), the word for ‘one’ was oinos before it later changed into ūnus. This word could be negated using the Old Latin ne, forming ne oinos ‘not one’. In the same way that Proto-Germanic *ne ainaz ‘not one’ underwent univerbation and became *nainaz ‘none’, ne oinos became noenum ‘not’, which (possibly) became the Classical Latin nōn. (Etymologists aren’t entirely certain of nōn’s origin, but this etymology is the best hypothesis.) English later borrowed the prefixed form of this, non-, from French, and it now appears in many words such as nonplussed, nonbeliever, nonfat, and countless more.

The last Latin-via-French reflex of *h₁óynos is a close parallel to non-. A step lower than Old Latin on our etymological tree is Proto-Italic, which is the ancestor of all the Italic languages. Latin and its descendants are the only languages in this branch that survived, but we have historical records of other Italic languages such as Faliscan, Umbrian, Oscan, and Picene. A few other languages for which we have little documentation might have belonged to the Italic branch as well (Venetic, Siculian, and Lusitanian).

In Proto-Italic, the word *oinos ‘one’ could be given a diminutive suffix to make it *oinolos ‘little one’. Just like *oinos, *oinolos was often negated as *ne oinolos ‘not (even) a little one’, and by the time of Classical Latin that phrase had become the word nūllus ‘no, not any’. In French it became nul, and English then borrowed it as the word null.

We’ll end our climb around the Romance branch of our etymological tree with a quick look at those words borrowed directly from Latin, usually during the Renaissance. These are the most straightforward of the lot:

Latin ūnītus ‘united’ and ūnītās ‘unity’ were borrowed as English unite and unity respectively, and unit in turn comes from an alteration of unity (by analogy to digit).

You might expect that the English word unary was borrowed directly from a Latin word like *ūnārius, but no such word existed in Latin. Instead, unary was modeled on the pattern of binary and ternary, using ūnus as the base.

There are various other words with a uni- prefix as well, such as uniform ‘one form’, unilateral ‘one side’, unicorn ‘one horn’, and unanimous ‘one mind’.

(Interestingly, unanimous actually displaced the native Old English word ānmōd ‘one-minded’.)

Now at this point you might be asking, “When does this article end?” and “Those are only two branches of Indo-European. Did English borrow *h₁óynos-derived words from other branches, too?” Well, I’ve got good news for you: I can answer both of those questions at the same time. Somewhat surprisingly given how many other branches of the family there are, there’s only one other reflex of *h₁óynos that I could find in English, and that comes from the Celtic branch of the Indo-European tree. So for our last stop on the etymological tour of ‘one’, we turn to Celtic.

Celtic

The Celtic branch of Indo-European contains Irish, Welsh, and Scottish Gaelic, just to name a few of its largest members. The Proto-Celtic version of *h₁óynos was *oinos ‘one’ (just like Proto-Italic), and this word appeared as the first part of the Old Irish name Oíngus. The second part of this name is uncertain, but it is either from Proto-Celtic *gustus ‘strength, vigor’ or *gus- choose’, meaning either ‘one strength’ or ‘one choice’. In Modern Irish and Scottish Gaelic, this name has become Aonghus. In 8th-century Pictish (another Celtic language), however, the name was Óengus, and the Pictish king Óengus I ruled over a region of northeast Scotland which is today called Angus after him. This region, you might have already guessed, is home to a small breed of beef cattle called the Aberdeen Angus (Aberdeen being another county) or simply Angus. Angus beef is thus the last leaf on our etymological tree.

Hidden Patterns in the Web of Linguistic History

Frequency is the erosion of historical linguistics: given enough time, even the most obdurate linguistic boulder wears away under its influence.

I don’t know about you, but it never ceases to amaze me a) how many modern words can derive from just a single historical root, and b) how incredibly different those words can be, both in their forms and their meanings. Just to drive the point home, here are all the English reflexes of *h₁óynos discussed in this article:

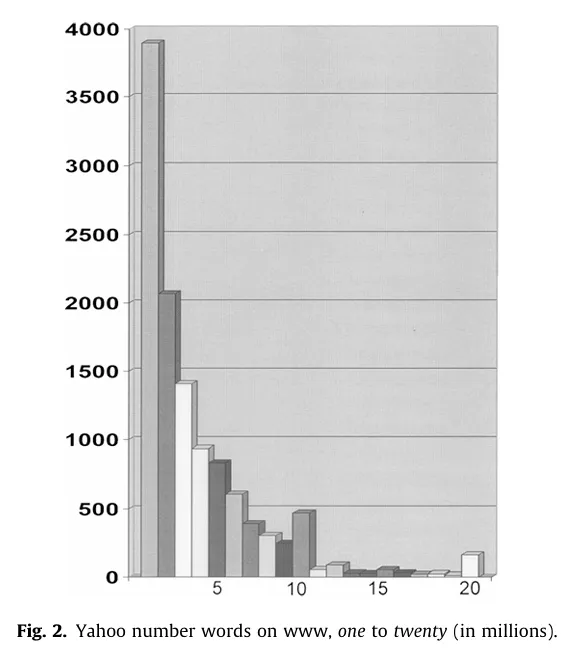

It’s to be expected that ‘one’ would be especially multifaceted, because words for ‘one’ are used more frequently than any other number (Coupland 2011), making them prone to univerbation like in the case of none, or to becoming a function word like in the case of a/an. Words for ‘one’ are incredibly versatile words in the world’s languages.

One tendency that may have stood out to you over the course of our scamper through the etymological tree is that the same word structure and concept can develop independently in different branches of a family, or multiple times in the same branch. Both none and non- come from a construction meaning ‘not one’, for example, while both any and unique are etymologically ‘one-y’. Proto-Germanic had the suffix *-līkaz ‘-like’, which became the Modern English -ly suffix, but Modern English also uses like as a suffix, e.g., catlike. This isn’t entirely coincidental. Some concepts are simply a common part of the human experience. In other cases, the development of a word or phrase in one language is due to influence from another. Part of the reason that Old English ān developed into the indefinite pronoun a/an was influence from French and Latin, for example.

It’s also important to consider what you’re not seeing when you look at these reconstructions. Do you really think that Old Latin didn’t have a way of expressing ‘not’ before it developed noenum? Of course it did! Anything else would violate the Uniformitarian Principle, the assumption that the laws and principles of nature operate the same way today as they did in the past. In the context of linguistics, this means that we expect ancient languages to behave similarly to languages today, because the humans of 2,500 years ago are not meaningfully biologically different from us today. Since every known language today has a way to signal negation, it’s implausible that Old Latin wouldn’t have.

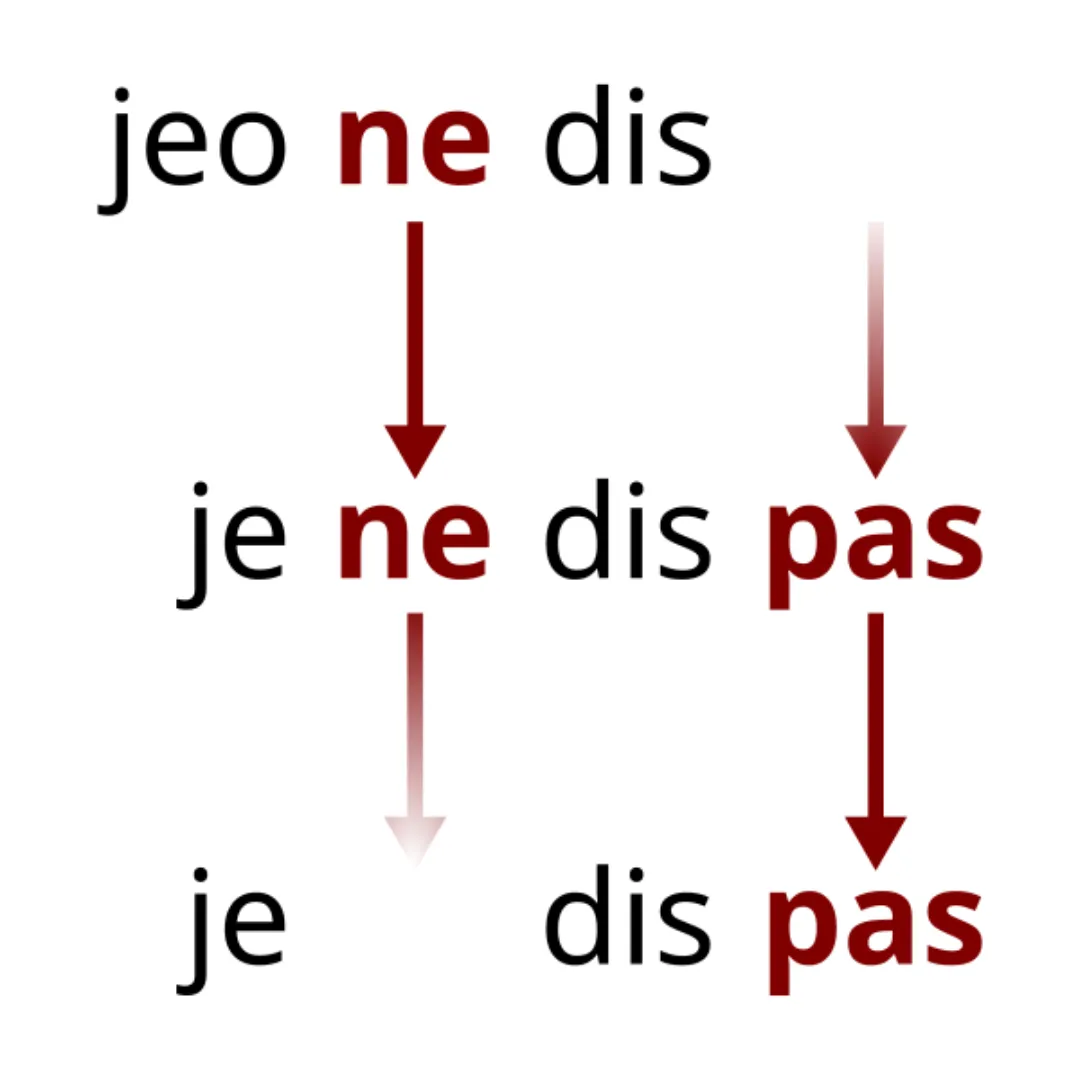

Why, then, did Old Latin speakers bother creating the word noenum if they already had a way of doing negation‽ Simply put, words lose their novelty with repeated use, and the more frequently a word is used, the faster this happens. When a word becomes less novel, speakers have to reinforce its meaning with other, sometimes seemingly repetitive words. Consider the famous example of French negation: Old French originally had just one negative, ne, but this lost its pragmatic strength, so speakers introduced a second negative, pas. This “double negative” isn’t logically contradictory, because the second negative isn’t functioning to negate the first—it’s functioning to reinforce the first. (The same holds true of double negatives in English, by the way.) This process of renewing negatives in languages is called the Negation Cycle or Jespersen’s Cycle.

Another reason speakers have to coin new ways of saying the same thing is that frequent words are phonetically reduced over time. The word not in English is now reduced to just -n’t in many cases, and phonetically this is sometimes realized as no more than slight glottalization on the preceding vowel. The phrase can not was once pronounced [kæn nɑt] in American English, but is now pronounced as merely [kæ̃n] in certain dialects—almost exactly the same as can [kæn]! This makes it incredibly hard for non-native speakers to hear the difference, and even native speakers can mishear it at times. How long until English needs another negation?

This process of renewing old words that have become meaningless and phonetically reduced is called, fittingly enough, renewal, and it explains why we see parallel structures develop in different branches of a family tree. If the protolanguage had a particular construction, and that construction was frequently used, then over time the child languages will need to find innovative ways of expressing that same function as the old structures wear down. Frequency is the erosion of historical linguistics: given enough time, even the most obdurate linguistic boulder wears away under its influence.

And so we come to the end of our etymological journey. Below is a complete map of the territory we covered along the way. Thank you for reading, and I hope you’ve enjoyed this special thank-you issue of the Linguistic Discovery newsletter!

If you enjoyed this post and want to support my mission to educate the world about linguistic diversity, consider becoming a supporter! Paid subscribers also get occasional bonus articles and early access to chapters of my book!

🙏 Credits

This issue of the Linguistic Discovery newsletter was edited by Amy Treber. If you’re looking for professional copyediting services, email Amy at amytreberedits@gmail.com.

A huge thank you also goes to Ryan Starkey for his willingness to collaborate on this infographic and to serve as an independent check on my research.

The final responsibility for any mistakes or omissions is of course still wholly my own.

🔀 Infographic

Below you’ll find my own (less pretty) version of the infographic that Ryan Starkey created for Starkey Comics. Since I had already written the article when Ryan started work on the infographic, you’ll notice differences! And since understanding these differences is also educational, here are some quick notes on them:

- The Starkey Comics version includes both the Old English and Middle English versions of words when relevant, whereas the Linguistic Discovery version conflates these two periods. Ryan separated them because in many cases these words entered into English in the Middle English period rather than Old English. (I conflated them primarily because of the space limitations with my format.)

- The Starkey Comics version uses PIE *óynos as the reconstruction for ‘one’ whereas the Linguistic Discovery version includes the initial consonant, as *h₁óynos. The reason for this discrepancy is that scholars of historical Indo-European disagree about whether to reconstruct this word with an initial consonant. While on the one hand there is pretty much no evidence in any of the daughter languages that *(h₁)óynos started with a consonant, it’s also generally accepted that PIE words never began with a vowel. So any words that are reconstructed with an initial vowel, like *óynos, are assumed to have actually started with *h₁, which then disappeared.

📖 Recommended Reading

❓ Uncertainties

The Modern English word alike seems to come from a conflation of the Old English words ānlīċ ‘only’ and ġelīċ ‘like, alike; similar; equal’.

The surname Einstein is a habitational name, meaning that it’s derived from the name or description of a place where someone lived. In this case, the original term was Middle High German einsteinen ‘to enclose or surround with stone’. This word could be broken down in one of two ways:

- ein- ‘into’ + Stein ‘stone’

- ein ‘one’ + Stein ‘stone’

If it’s the second possibility, then the name is also related to one, since German ein also descends from PIE *h₁óynos. But I think the former etymology is more plausible.

Silas Frisenette points out that some compound forms like Proto-Germanic *nainaz ‘none’ and Proto-Italic *noinolos ‘none’ might actually trace all the way back to Proto-Indo-European, as *n-óyno- ‘none’ and *n-óyno-los ‘not a little one’, respectively. It can be hard to pinpoint exactly when the languages created these forms (whether it happened in Proto-Indo-European or later, after the languages had diverged), but the evidence does suggest both of these forms are older. If those words were formed during the period of Proto-Germanic and Proto-Italic, you’d expect them to be something like *unainaz for Proto-Germanic and *inoinos for Proto-Italic, because by that point the negative prefix had become *un- in Proto-Germanic and *in- in Proto-Italic.

📑 Sources

- Barnhart, Robert K. (ed.). 1988. Chambers dictionary of etymology. Chambers.

- Coupland, Nikolas. 2011. How frequent are numbers? Language & Communication 31(1): 27–37. DOI: 10.1016/j.langcom.2010.09.001

- Etymonline: *oi-no-

- Harrison, K. David. 2007. When languages die: The extinction of the world’s languages and the erosion of human knowledge. Oxford University Press.

- Ringe, Donald (ed.). 2006. A linguistic history of English, Vol. 1: From Proto-Indo-European to Proto-Germanic. 1st edn. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199284139.001.0001.

- Watkins, Calvert (ed.). 2011. The American Heritage dictionary of Indo-European roots (3e). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Wiktionary: *h₁óynos

🔠 Abbreviations Used in this Article

| L | Latin |

|---|---|

| ME | Modern English |

| OE | Old/Middle English |

| OF | Old/Middle French |

| OI | Old Irish |

| OL | Old Latin |

| P | Pictish |

| PC | Proto-Celtic |

| PG | Proto-Germanic |

| PI | Proto-Italic |

| PIE | Proto-Indo-European |

If you'd like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

Check out my entire Amazon storefront here.